The end, when it came, was fast and surprising.

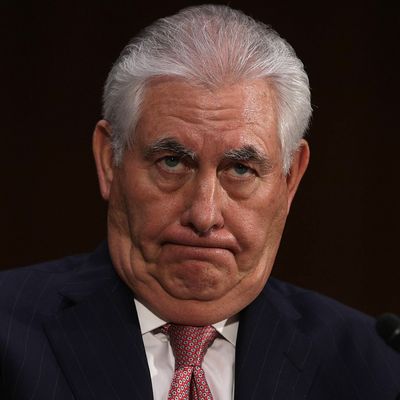

Rex Tillerson, whose departure had been rumored for months, who survived both being caught calling the president an effing moron and refusing to deny it, finally fell victim to … Kim Jong Un? Or his aggressive remarks about Russia yesterday? Or Donald Trump feeling his oats and indulging an impulse he’d been suppressing for months? The exact causality, alas, remains murky. In any case, the entire world was surprised to learn Tuesday morning that Tillerson was out at State.

The story broken by the Washington Post had Tillerson — who seemed to have been cut out entirely from the decision to go ahead with a Trump–Kim Jong Un summit, and who had then gone ahead and left on a previously planned trip to Africa — being called home by Trump in order to be fired.

This being the Trump White House, even that story quickly got complicated. Monday, giving no inkling of what had happened, Tillerson got out ahead of the White House on a sensitive matter, explicitly blaming Russia for the nerve-agent attack on a former Russian spy in the U.K., and promising it would “certainly trigger a response.” Some commentators jumped in to assert this was the true cause of his firing. Others — including former Trump advisers — saw it as one last subtweet of a boss Tillerson had long disrespected. But within an hour of news of the firing breaking, a State Department spokesman told reporters that the (now ex-)secretary had no idea it was coming:

Either way, Tillerson seemed to have lived out his Cabinet lifespan months ago. He was caught crossways of Trump on policy so many times this analyst stopped counting — on North Korea, on trade, on Iran, on Europe. He was rumored not to be getting along with Defense Secretary Mattis and National Security Adviser McMaster — the Cabinet colleagues who had initially been his closest allies.

Within minutes of the news breaking, Washington was scurrying to analyze his successor, Mike Pompeo, a former Kansas congressman who has most recently served as CIA director. Pompeo is viewed by many as a more traditional Republican hawk, who will be tougher on Russia and Iran than Tillerson, whose previous career had included oil deals with both. Pompeo will be succeeded at the CIA by his deputy, Gina Haspel. A career officer, she gained notoriety for her reported leadership of one of the CIA’s notorious “black sites,” interrogating prisoners with techniques that constitute torture under U.S. and international law, and overseeing the destruction of videotapes of the interrogations.

Tillerson will leave a legacy, for sure. First, in the diminishment of his office — something which was not entirely his fault. Trump wasn’t the first president who couldn’t resist the temptation to be his own secretary of State, or to undercut his secretary to prevent him from gaining international stature that could rival his own. And as the National Security Council has grown in size and influence, and modern communications have allowed anyone to connect across national lines, State’s influence has been declining over the decades. But, with Trump’s gratuitous cruelty added to Tillerson’s missteps, Pompeo will get to Foggy Bottom with the prestige and clout of his office at its lowest ever. (It’s a long way down from Thomas Jefferson.) He may find that he misses the CIA.

Second, the State Department itself is — there’s no kind word for it — a mess. Tillerson achieved something that diplomatic geeks had tried and failed for 20 years — getting reporters, members of Congress, and even voters to care about State Department personnel policy. Not because he succeeded in reforming the Department to his vision, but because his ideas went so publicly awry. His plan to reform and restructure the State Department produced a steady leak of embarrassing PowerPoint slides and memos. Just last week a Politico reporter tweeted his deputy’s “Strategic Hiring Initiative” line by line, with commentary pointing out how much it seemed to presage further staff cuts. His ideas on personnel reforms — prevent spouses from working in embassies overseas, shut the pipeline of super-talented fellows entering the State Department out of graduate school, run every decision through a tiny team — produced headlines and outrage among people who had never cared much about State before.

More than 100 senior diplomats have resigned since Tillerson took office, leaving top ranks understaffed. At the same time, Tillerson canceled, delayed, or shrunk entire classes of new junior diplomats. As of last month, more than 100 ambassadorial positions were unfilled, as were many higher-level positions back in Washington. Not only is the department smaller, but most of its senior women, and officers of color, are gone — meaning that the service looks less like our country and less like the rest of the world with which it must interact. Gina Abercrombie-Winstanley, one of the senior ambassadors who chose to leave during Tillerson’s tenure, said: “No doubt we are as disappointed as he.”

But career foreign service officers tell reporters that they would prefer Pompeo, who has publicly opposed the Iran deal, State’s crowning achievement under President Obama, and endorsed rhetoric that will make dealing with Muslim nations even more challenging — because they believe he actually ran the CIA and will make an effort to do the same at State.

This brings us to Tillerson’s final legacy, which is very far-reaching indeed. For more than six decades, Americans have simultaneously built up a specialized security bureaucracy and told themselves that any businessman (and it was always men) could do better than the people who’ve spent decades working inside it.

Tillerson wasn’t just any businessman. He had run an immense corporation and was well-regarded at home and abroad. He was certainly not as foolish as he was often made to appear. And yet, he would certainly have been better served by humility: both about the abilities of the men and women he led, and about his own limitations in trying to manage a president who prides himself on being unmanageable. Tillerson came in expecting to own American foreign policy. In the end, he’s the one who got owned.