In California’s top-two (or as some describe it, “jungle”) primary system, all candidates are thrown into one big pool, and then the first- and second-place finishers, regardless of party or percentage, advance to the general election in November. That means it is entirely possible in any given race that one of the two major parties can be “shut out” of the ultimate contest. When it happens at the top of the ticket — as it did in 2016 to Republicans, who failed to place anyone in the top two in the U.S. Senate race eventually won by Kamala Harris — it can have an impact on turnout in down-ballot races. With a host of nationally critical U.S. House races taking place in California this year, Republicans fear that getting shut out of the Senate and gubernatorial elections could be costly.

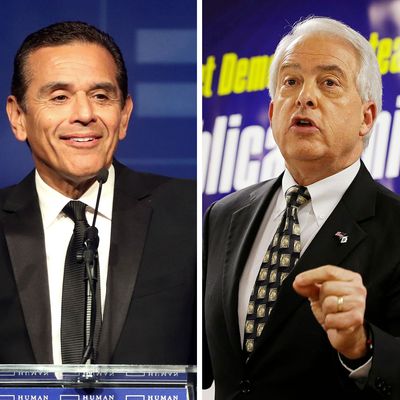

That’s almost certain to happen in the Senate race, where there are only two candidates with enough name ID and money in the vast field of 37 hopefuls on the ballot to have a realistic shot of finishing first or second. Both are Democrats: incumbent Dianne Feinstein and state Senate Majority Leader Kevin de Leon. But in the gubernatorial race which has been led from the beginning by Lieutenant Governor Gavin Newsom, the fight for the second general-election spot is intensifying as the June 5 primary approaches. A new poll from the well-regarded Public Policy Institute of California shows former Los Angeles mayor Antonio Villaraigosa, a Democrat, and self-funding businessman John Cox, a Republican, in a close fight for second place.

PPIC, using a traditional phone-interview-based methodology with a large sample, has Newsom at 25 percent, Cox at a surprising 19 percent, and Villaraigosa at 15 percent, with 15 percent of respondents undecided. A second Republican, Travis Allen, is at 11 percent, while two other prominent Democrats trail the pack with single-digit showings.

The poll’s surveys were taken between May 11 and May 20, so they may only slightly reflect the impact of Donald Trump’s May 18 endorsement of Cox, intended to consolidate Republican support behind its beneficiary at the expense of Travis Allen. It appears Cox is in pretty good shape anyway, though a large ongoing ad campaign on Villaraigosa’s behalf financed mostly by a national network of wealthy charter-school supporters, will likely boost the Democrat’s standing going down the stretch.

A look at PPIC’s internal findings shows that the ideological typecasting of the candidates can be misleading in terms of their base of support. Villaraigosa is generally thought of as the “centrist” Democrat in the race, with some crossover appeal to Republicans. In fact, his support is heavily ethnic: He is currently favored by 39 percent of his fellow-Latinos, and is running a poor fifth among white voters. You’d normally think progressive favorite Newsom would do best among younger voters, but reflecting the younger age of the Latino demographic, Villaraigosa leads the field among voters under 45 and is running far behind Newsom and Cox among voters 45 and older.

The ethnic factor comes into even sharper relief when you look at PPIC’s breakdown of the Senate race, where Feinstein has a solid 41/17 lead over de Leon among likely voters (a very large 38 percent are undecided, reflecting the low profile of this race so far). De Leon is the candidate of progressives disenchanted with Feinstein’s history of intermittent ideological heresy and relative friendliness toward Republicans. Yet PPIC shows her crushing de Leon among self-identified liberals by a 63–18 margin. What’s keeping de Leon in the race is that he’s essentially tied with Feinstein among his fellow-Latinos. This gives him a base for expanding his support between now and the general election if he and his progressive allies can succeed in raising doubts about the incumbent among left-bent rank-and-file voters.

In Villaraigosa’s case, the question is whether his ad blitz can expand his base of support beyond Latinos as rapidly as Cox consolidates Republicans behind his candidacy. It’s no secret that some progressives would be willing to sacrifice the down-ballot turnout advantage of an all-Democrat general election for governor in order to give Newsom an easier path to election while sidelining Villaraigosa’s billionaire backers with their charter school agenda. Newsom himself has run at least one ad attacking Cox in a manner that seems transparently designed to boost the target’s appeal to conservative voters.

It is Democrats who have fears of being “shut out” of general elections in some of those key House races in Southern California thanks to a surfeit of candidates. But where there are a Republican and a Democrat in the general election, overall turnout will matter, and having a candidate in the big statewide races could matter, too, at least at the margins. Republicans hope a ballot initiative to overturn a gas-tax increase that has enraged conservatives will more than compensate for top-of-the-ballot weakness. But they’d prefer to have John Cox out there every day bashing Gavin Newsom as a tonic to the troops.