This story is a collaboration with WNYC, which has a new five-part series on the gang bust and its aftermath.

On April 27, 2016, police officers and federal agents arrested 120 members of two rival crews in the North Bronx, the Big Money Bosses and 2Fly YGz, in what’s believed to be the largest gang takedown in city history. Law-enforcement officials said the two crews “terrorized” the neighborhoods they lived in, killed at least eight people, most in their teens and early 20s, and that together 2Fly and BMB earned as much as $1.5 million between 2014 and 2016 selling cocaine, marijuana, and oxycodone. In announcing the indictment, then–U.S. Attorney Preet Bharara said that the charges would help free New York public housing of violence and drugs. The New York Police Department has adopted gang and crew takedowns as a crucial crime-fighting tool since it started moving away from stop-and-frisk back in 2012. They’re part of the NYPD’s precision policing strategy — using data and intelligence to identify a small number of people who are committing the majority of violent crime.

In the community the reaction was divided: Some residents welcomed the takedown and a quieter neighborhood, others said they weren’t even aware of the gangs’ presence and that the sweep had drawn in young men with only tangential connections to the crimes. “This really only happens in black communities, in the minority communities, in Hispanic communities,” said one young man during a community meeting with cops shortly after the bust.

Over the past two years, competing narratives have continued to emerge. In federal court, 2Fly and BMB have been described as violent gangs that wreaked havoc for years on their communities and whose takedown has brought much-needed peace to the area, allowing people to be outside without the fear of getting shot. In the community, it remains unclear if the takedown will lead to long-lasting low crime rates, and how, in Eastchester Gardens, which is surrounded by low-performing schools and where 60 percent of the residents are unemployed, things will change for the next generation.

Becoming part of a gang is easy.

Aaron Rodriguez, 26, 2Fly leader: I’m young. I’m like 13, 14. I’m hearing about this gang that’s going around in the Bronx. 2Fly YG, 2Fly. They seemed like the guys that you wanted to be with. They got the girls, they got the clothes, everything. Now I get arrested, I’m in juvenile. I meet this dude that was part of the gang. We ended up kicking it. One thing led to another and I joined the gang. It wasn’t any initiation or jumping or I gotta beat somebody. I wanted more out of it as far as being a bigger member, having my name more out there. Who wants to be a small fry your whole life? It’s like having a job. Eventually you wanna be a manager.

Rasheid Butler, 21, identified by prosecutors as a BMB member: I was following after my brother. I didn’t see him going to school, so I didn’t want to go to school. He outside chilling with his friends. A’right, I wanna chill with y’all too.

Aaron Rodriguez: I was the product of my environment basically. This is what I was around so this is what I became. The violence, the drugs, the lifestyle. The robberies. This what I thought was right at that time. But on the flip side of it I was also the aggressor, knowing that these things was wrong, that I was breaking the law. I could have stopped, but I didn’t.

Lloyd Rodriguez, 22, 2Fly associate, Aaron’s brother: I sold weed. You stop going to school, your parents won’t support you. So I had to keep some money in my pocket. So that’s what I did. I would just buy little packs and just flip ‘em. Just a way to keep money in my pocket and I ain’t have a job.

No one seems to know how the rivalry between the gangs started.

Aaron Rodriguez: It was never really about 2Fly and BMB. It was more so about where we was from and where they was from.

Butler: White Plains had beef with the Valley. That’s like a generation thing. Even the older people from our block … they said it’s like history repeating itself.

Lloyd Rodriguez: When you grow up and certain people don’t like you, you just grow not to like them. And that’s just what it becomes. They don’t like me, because I’m from here, then I’m not going to like them because they don’t like me. That’s just as simple as that.

Aaron Rodriguez: At first it was like a territorial thing. As time went on, it became more than that. It’s been going on for so long, it got to the point where it didn’t make sense anymore. We just having issues to have issues. Not fighting towards anything. It was just more of Okay, you from over there. We’re gonna see if we can kill you.

Between 2009 and 2014 six people were killed in the rivalry between the two gangs, according to law enforcement.

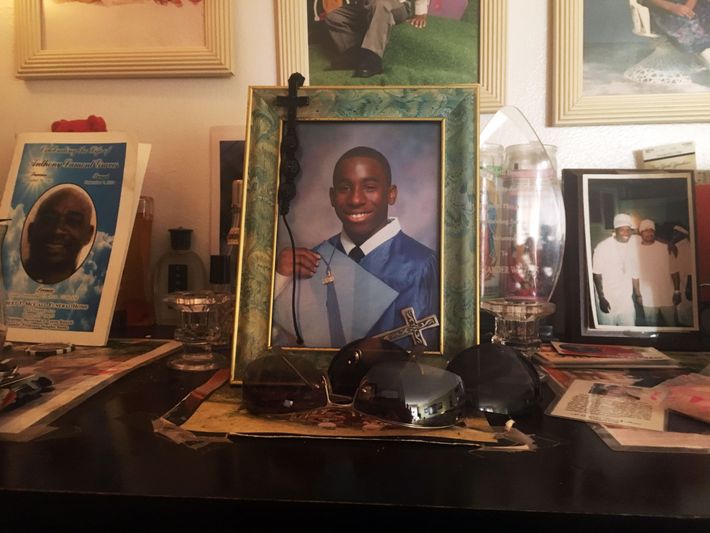

Godeen Walters, 50, the mother of Donville Simpson: He’s my only son. He was six-foot-four. Very quiet. He love to eat Jamaican food. And he love basketball. He played basketball so much that he messed up his back. He is a gift to me, not only because he was my only son, but he spent more time with me, more than his two older sisters. He was more clingy to me.

Alexander Walters, 54, the father of A.J. Walters [no relation to Godeen]: A.J. was a very outgoing person. He was athletic. He was a receiver, running back, and a defensive end. He used to dance on the subway. We all like to dance. It’s a Walters thing.

Godeen: When Donville arrive here, he didn’t have no friend ’cause we used to live in Yonkers. That’s when Donville and A.J. started to talk.

Alexander: [On March 8, 2012] I was coming home from work. I got a call from my brother stating that something bad had happened to A.J. They told me we need to get to the hospital, but they was willing to pick me up at the train station. When I came up on the Gun Hill station, there was a lot of commotion. Found out later that’s where the situation happened at. They was fighting outside. It was a melee outside. It end up going inside one of the grocery stores over there. That’s where he got stabbed, inside one of the stores.

I went into the emergency room. They said it was a stabbing to the left side of his body, underneath his arm. It had punctured his heart. The way that the surgeons looked at me was like they were just going through the motions, like they know, at the end of it, he was going to pass.

Donville was there. He was there until the end. He was holding him [A.J.] until the ambulance came.

The NYPD made an arrest a day after A.J. Walters was stabbed, but the Bronx district attorney didn’t file charges in the case.

When they found one of the guys, they said that he was the culprit that did it, but nobody wanted to talk. Even people that was there, they said they wasn’t there. You hear it all the time that nobody want to snitch. So they arrested him, but then they couldn’t indict him. They had no real hard evidence. They said just lay back and let them try to get evidence on him. Maybe he gonna crack, say something on his phone or, you know, give stuff away. So we’ve been waiting for that to happen, but that never happened.

Godeen: [A year and a half later, on October 4, 2013] I send him [Donville] out there to celebrate his 17th birthday. I’m giving him a little independence because every birthday he celebrate with us.

He went over by the project to meet up with some guys. While he was outside waiting, some guys came and started to shoot. That was it. He just didn’t came back home. The guys who were there and the other guys, they have something going on between them. He get caught up into it.

The first birthday he get to celebrate by himself, it cost him his life. It shouldn’t have to because we’re not living in some third-world country, where gunshot is everywhere. This is New York, America. A child is supposed to be free to leave their house and go out and come back.

The day of the funeral, I stood around the coffin, by Donville, for one hour straight. I just couldn’t move. I wasn’t crying. I just stood there and I put my hands behind his ears. When I touch him, it was cold. By the time I took my hands off him, his ears was warm. When they told me they were going to close the casket now, I must sit down, I said, “No, I want to close it.” I should be the last person. I was the first person there to receive him.

About a year after Donville Simpson was killed, cops arrested Jaquan McIntosh, a 2Fly member. The Bronx district attorney’s office began preparing for a murder trial.

Jason Wilcox, chief of detectives in the Bronx: Murder like that of Donville Simpson is a case in point, where it starts off with the detective squad, and then it grows into Bronx’s narcotics looking at it. Then it goes into Bronx gang looking at it and making connections and building a case. It takes a long time.

That was the beginning of a very violent summer in the 47th Precinct. Lots of shootings, lots of violence, and out of that violence came investigations into what’s going on and to what groups are fighting with who and who’s selling drugs.

The spike in violence attracted the attention of law enforcement.

Deputy Chief Ruel Stephenson, former commander of the 47th Precinct: My very first day here I was dealing with the escalation in violence as it relates to the Big Money Bosses and the 2Fly crew. We sat down with our detective squad and our field intelligence unit and we identified the core members within the gang and the individuals that we had in the database. These are the alpha males, the individuals who were calling the shots. We started looking very closely at them and monitoring their activity, whether social media and their contacts with us.

In December of 2014, the NYPD launched a formal investigation.

We had started out around 25 to 30 individuals. As the investigation got more in-depth, we started seeing connections with more individuals to these targeted members. The number increased. That’s the origin of the investigation that brought us to April 27th of 2016, where we had 120 that were involved in the indictment.

The Bust

On April 27, 2016, 700 agents from NYPD, Immigration and Customs Enforcement, the Drug Enforcement Administration, and the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives descended on locations across the Bronx.

Butler: Probably around three or four o’clock in the morning I hear banging on the door. I hear my mom go get the door. She goes, “Why y’all looking for him?” I guess they have my picture, so my mom calls me. “Rah!” I gets up. I walks to the door in my boxers. I looks out. I see like 30 cops. I see ICE, ATF, DEA, Homeland Security, NYPD. I’m like, “I don’t got any warrants.” So one of the officer steps in. He like, “You put your hands behind your back,” and he arrest me. “Yo, what am I being arrested for?” He like, “You’ll find out when you get there.”

So he about to take me outside in my boxers. I’m like, “Yo can I at least get some sweat pants and my sneakers, a shirt or something?” So he like, “You can’t go get it. But if she want to go get it for you she can.” I told my mom go get my sweatpants, some sneakers, and a shirt.

I goes outside, I see a helicopter in the air and everything. I start thinking, Oh wow, there’s got to be an indictment. They go pick me up on a BMB indictment. We always knew an indictment would happen, but I didn’t think I would get indicted. I know what my friends out there doing. So it was just a matter of the time before they came and actually got us.

Pastor Timothy English, chairman of the nonprofit Bronx Clergy Criminal Justice Roundtable: My first reaction was Oh my God and Who was involved? We were trying to get a feel for the impact. And then immediately after that was the emotion of that was wrong. That shouldn’t have happened. Obviously, every law-abiding citizen wants those who are bent on harming the community you know to be dealt with. But I was troubled by the magnitude of it.

The life of the community is young people. You want to hear laughter, you want to hear kids on the streets. You want to see them playing basketball in front of the fire hydrant. It’s … I can’t describe it. You feel something is missing. It’s almost like after a major storm or catastrophe, where valued aspects of the community are missing. The houses are blown down. It feels like that, like something really happened.

Aaron Rodriguez: I was in my child’s mother’s house, sleeping, me and my son, my child’s mother. When they said they had a warrant for me, I started laughing. You got the wrong person, I’m thinking. Then they said they was looking for my little brother. That’s when I know it wasn’t a joke.

Lloyd Rodriguez: I was setting up everything for me to start becoming a correctional officer and then the indictment happened. Actually I didn’t even know I was involved at first. My mom had called me and she had told me that my brother had got arrested. And then like a lot of people started hitting me up like, “Oh, they’re looking for you too.” That’s when my mom told me. I guess she ain’t want me to panic and nothing. I stayed down there [in Virginia, where he’d moved] for like two months before I turned myself in. I was working. I was saving money, because I didn’t know how long I was going to be away.

Aaron Rodriguez: I was making steps, in a way, to change my life, you know, start working, programs. I wasn’t hanging around certain people no more. It came as a shock as opposed to when I was ripping and running, had all these things going on. And now when you least expect it, I get caught up in this.

2Fly and BMB members faced racketeering conspiracy, narcotics conspiracy, narcotics distribution, and firearms charges.

Stephenson: We didn’t just red flag these individuals at the local level, the state level, the district attorney’s office. We decided to partner with the Southern District. When they realize that they are not going to the courthouse on 161st Street, that they are going down on the FDR bypass, it’s something to talk about. Even some of the toughest of the tough, when they find out that their case is being handled by the Southern District, they become very, I would say, cooperative.

Butler: As soon as I walk in the precinct I hear “Big Money, Big Money, Big Money.” I asked one of my codies, I was in the bullpen, I’m like, “Yo, what we even being charged with?” He like, “We getting RICO, racketeering.” I never knew what the RICO was until then. I’m going, “What’s the RICO?” He barely even knew what it was. He like, “The RICO is what John Gotti got.”

Steven Cohen, federal prosecutor and former chief of the violent gangs unit in the Southern District of New York: The racketeering laws were originally passed as a federal answer to traditional organized crime. Everybody assumed that the application would largely be in cases involving traditional organized crime, La Cosa Nostra. Yet the bigger problem in urban areas in the ’70s and ’80s increasingly became very violent drug offenders in local communities. That problem was one that ultimately a bunch of prosecutors realized, working with the police department, might well be dealt with through these racketeering laws. It was almost stumbled upon.

There was a little hostility initially from the courts, but ultimately we got a bunch of very favorable decisions, and now we had a mechanism. We could charge these organizations as racketeering enterprises. And it was, in the world of law enforcement at the time, a real opportunity to change up enforcement, so that you weren’t doing these one-off cases. We ended up working very closely with the police department identifying what gangs in which neighborhoods really were the most persistent problems and then prosecuting the whole gang, pulling them out, roots and all.

Babe Howell, CUNY law professor: [Conspiracy] is very easy to charge and has been called the darling of the prosecutor’s nursery. The reason is because all they have to prove is an agreement and the specific intent to commit the target crime. If five people agree to “Let’s go rob the bank on the corner,” if any of those five take an overt act, buying a gun, or getting ski mask, or looking up the hours of the bank, if any of those five make an overt act in that direction, then a conspiracy charge can be proven.

To use that against crews … The way a child ends up in a crew is very much, especially in public housing, I grew up in this building, on this block. I have spent my entire life here. These are the kids who are in my kindergarten class. These are the kids that are at my playground. These are the kids that are on my floor. You are in a crew before an age when you could make binding agreements. You are not agreeing when you join the Thompson Avenue Boys to commit any sort of target crime.

Prosecutors say that on June 20, 2014, Butler went to a party to back up a BMB leader, who shot and wounded two people, including an innocent bystander, a 16-year-old girl who was waiting for a bus.

Butler: Something went off and they said I had a part in it. I was at a party. I ain’t go there with no intentions of anybody getting shot. I was just at a party in my neighborhood and somebody just happened to get shot.

He was facing racketeering conspiracy, drug conspiracy, and firearms charges. The latter two carry mandatory minimums of ten years. By the time Butler pleaded guilty, in December of 2016, 25 of his BMB co-defendants had done the same.

Butler: More and more people starting to cop out. So I’m, like, I’m not trying to be one of the last people to cop out. So I tell my lawyer, like, try and get me the best cop-out you can because it don’t look like I’m going to be able to go home.

Lloyd Rodriguez: I was there for ten months. They [his lawyer and the prosecutors] was probably going back and forth for about the first six months. I feel like the DA [assistant U.S. Attorney] wanted me to play a bigger role. Because she felt like who my brother is that I should’ve played a bigger role, that they just couldn’t piece it together. But it wasn’t as deep as she tried to make it seem. I was just like let me cop out to the weed so I could just get it over with.

Butler: I’m like a’right if I cop out to the RICO the judge is gonna see that I didn’t personally shoot anybody. So I’m like it probably wouldn’t be that bad on me. And people that was actually associates of BMB, that wasn’t actual members, she was being more lenient with them. My record is not that bad. I just got that one juvenile case. I goes to get sentenced. When [the judge] said 133 months imprisonment, I’m just thinking, like, Wow, she just gave me 11 years. I was hoping for seven or eight.

Aaron Rodriguez: Given everything that we worked hard on getting, as far as showing them the type of person I really was and where I came from, I thought that I would have a little more leniency. But it didn’t play out that way.

Jed Rakoff, federal judge in the Southern District of New York: Anyone who is arrested and charged in a criminal case is facing the same dilemma. Do I put the system to the test? In the old days, if you put the system to the test, and you still were convicted, you would face a sentence that was probably no more than 10 percent higher than what you would face if you pled guilty. Now you face a sentence that may be 500 percent higher than if you pled guilty.

The result is that people, including unfortunately many innocent people but also many guilty people who nevertheless would have put their case to a jury, because they felt there were extenuating circumstances, no longer choose to go to trial. For many decades before the 1970s between 15 and 20 percent of all criminal cases went to trial. After the mandatory minimums and other laws were passed, that percentage went down dramatically. Now it’s down to 3 percent going to trial, which is, I think, a very unfortunate result.

It’s very bad for the system because a trial is the one place where the system as a whole gets tested and where you find out what the truth is. And instead what we have is a system where everything is negotiated in secret in a prosecutor’s office, and you never find out what the truth is or whether the system was working.

In the April 2016 indictments, prosecutors claimed Donville and A.J. were victims of the 2Fly gang. According to court documents, Donville was a member of the Big Money Bosses and had gone to Eastchester Gardens to shoot at his rivals in the 2Fly crew. Jaquan McIntosh, who was awaiting trial for Donville’s murder, was transferred to federal custody as part of the racketeering conspiracy. He pleaded guilty, and Godeen Walters gave a victim’s impact statement in federal court in July of 2017.

Godeen: My daughter had me put on a little blonde wig. I wear a white silk shirt, black pants, and a little heel. I pray that day to have boldness and confidence and love. I shall not go in there with hate. I did not say a bad word about that boy. I did not address him. I did not acknowledge him because in my head he’s already buried. Why would I waste my breath on someone who don’t give a rat about life, somebody’s life? The only thing you have left as a parent is to get some justice, some kind of justice for your child.

Federal prosecutors say that the 2Fly crew is responsible for A.J’s death, but they haven’t identified the person who stabbed him.

Alexander: Hopefully one day I get a closure. Hopefully. Some people don’t.

Ultimately 111 people out of 120 pleaded guilty. Two cases went to trial resulting in guilty verdicts. By early August of 2018, 48 of the original defendants are out of prison.

Deputy Inspector Thomas Alps, commanding officer of the 49th Precinct in the Bronx: I’ve heard nothing but positive reaction from the residents of Eastchester [Gardens] to the takedown. They finally feel as if it’s safe for them to enjoy the grounds, be outdoors. I have slim to no violence up there now, really no crime per se.

Our objective is to give the good residents over there a peaceful environment. And it’s obvious by the stats. It’s obvious from speaking to the residents that it was successful. And it’s made my life as a commanding officer here at the 4-9 precinct a lot easier.

Butler: The only thing I don’t think was fair was the amount of time I got for something that I didn’t actually physically do. Eleven years for being at a party and a shooting happened. I don’t think I would have even gotten in state that much.

When I go home, I just know not to affiliate myself with certain crowds. I don’t regret anything. I really don’t. You live life and you learn. Unfortunately, I learned the hard way. My teenage life was a wild one, but, I mean, this is the end of it now. This is like a changing chapter in my life. So when I go home, I’m gonna be a grown man. There’s no more teenage years.

[Dropping out of school] is probably the only thing I regret. I would have probably never got so much time if I would have probably had a high school diploma. The judge would have probably looked at me a little different, not straight as a criminal or a young black man from the Bronx.

Aaron Rodriguez: I don’t regret anything specifically that I’ve done. I just regret leaving people, leaving my family behind.

Lloyd Rodriguez: It’s like you have a stigma on you, and it’s hard to shake. I feel like that’s what this indictment did. It put me in a place where now I’m judged. Oh, you was one of them. You a felon now. I can’t do what I wanted to do originally. So I got to draw up something else. It’s hard. I got a job right now, in Applebee’s, but that’s not what I want to do. It’s just what’s given to me. Washing dishes.

Pastor English: How can we prevent that from happening again? Not to be anti-police, because it’s certainly not that. But how can we work with law enforcement as a whole community to get ahead of things, to get on the preventive side of things?

Lloyd Rodriguez: If the community was so bad and the projects was horrible, why are y’all releasing us back into that same spot? Like why don’t y’all help us come home to something different? My brother will be coming back to this, the same neighborhood. The cycle don’t stop. The same thing that happened with us was happening before us and before them, and it’s going to happen with the kids that’s younger than us. Because after the indictment nothing changed for the kids out there.

After a while the kids who was playing basketball in the park, start smoking in a park. And the kids who start smoking in the park, they start shooting in the park. It’s just the cycle.

Mirela Iverac is a reporter for WNYC.