The politics of Britain and the U.S. can have a strange, synchronized rhythm to them. Margaret Thatcher was a harbinger of Ronald Reagan as both countries veered suddenly rightward in the 1980s. Prime Minister John Major emerged as Thatcher’s moderate successor as George H.W. Bush became Reagan’s, cementing the conservative trans-Atlantic shift. The “New Democrats” and the Clintons were then mirrored by “New Labour” and the Blairs, adapting the policies of the center-left to the emerging consensus of market capitalism. Even Barack Obama and David Cameron were not too dissimilar — social liberals, unflappable pragmatists — until the legacies of both were swept aside by right-populist revolts. The sudden summer squall of Brexit in 2016 and the triumph of Trump a few months later revealed how similarly the Tories and the Republicans had drifted into nationalist, isolationist fantasies.

But what of the parallels on the left? What’s generating activist energy and intellectual ferment in both countries is an increasingly disinhibited and ambitious socialism. Bernie Sanders’s strength in the Democratic Party primaries two years ago was a prelude to a new wave of candidates who’ve struck unabashedly left-populist notes this year, calling for “Medicare for all” and the end of ICE, alongside a more social-justice-oriented cultural message. Some, like the charismatic Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, have achieved national visibility as an uncomplicated socialism has found more converts, especially among the young. Moderate Democrats have not disappeared, but they are on the defensive. A fight really is brewing for the soul of the Democrats.

And so it seems worth trying to understand what has happened in the Labour Party in Britain in the past few years. In 2015, in a flash, Labour became the most radical, left-wing, populist force in modern British political history. Its message was and is a return to socialism, a political philosophy not taken seriously there since the 1970s, combined with a truly revolutionary anti-imperialist and anti-interventionist foreign policy. This lurch to the extremes soon became the butt of jokes, an easy target for the right-wing tabloid press, and was deemed by almost every pundit as certain to lead the party into a distant wilderness of eccentric irrelevance.

Except it didn’t. Today, Labour shows no sign of collapse and is nudging ahead of the Tories in the polls. In the British general election last year, it achieved the biggest gain in the popular vote of any opposition party in modern British history. From the general election of 2015 to the general election of 2017, Labour went from 30 percent of the vote to 40 percent. It garnered 3.6 million more votes as a radical socialist party than it had as a center-left party. Hobbled only by a deepening row over anti-Semitism in its ranks, Labour will be the clear favorite to form the next government if the brittle Tory government of Theresa May falls as a result of its internal divisions over Brexit.

This success — as shocking for the Labour Establishment as for the Tories — has, for the moment at least, realigned British politics. It has caused Tony Blair, the most successful Labour prime minister in history, to exclaim: “I’m not sure I fully understand politics right now.” It comes a decade after the 2008 crash, after ten years of relentless austerity for most and unimaginable wealth for a few, and after market capitalism’s continued failure to meaningfully raise the living standards of most ordinary people. When the bubble burst ten years ago, it seemed as if Brits were prepared to endure an economic hit, to sacrifice and make the most of a slow recovery, but when growth returned as unequally distributed as ever, something snapped. The hearing the hard left has gotten is yet more evidence that revolutions are born not in the nadir of economic collapse but rather when expectations of recovery are dashed.

Revolution is not that much of an exaggeration. In the wake of capitalism’s crisis, the right has reverted to reactionism — a nationalist, tribal, isolationist pulling up of the drawbridge in retreat from global modernity. Perhaps it was only a matter of time before the left reacted in turn by embracing its own vision of an egalitarian future unimpeded by compromise or caveat. This is the socialist dream being revived across the Atlantic, and not on the fringes but at the heart of one of the two great parties of government.

Democrats should pay attention. Labour’s path is the one they narrowly avoided in 2016 but are warming to this fall and in 2020. It’s an English reboot of Clinton-Sanders, with Sanders winning, on a far more radical platform. And, politically, it might just work.

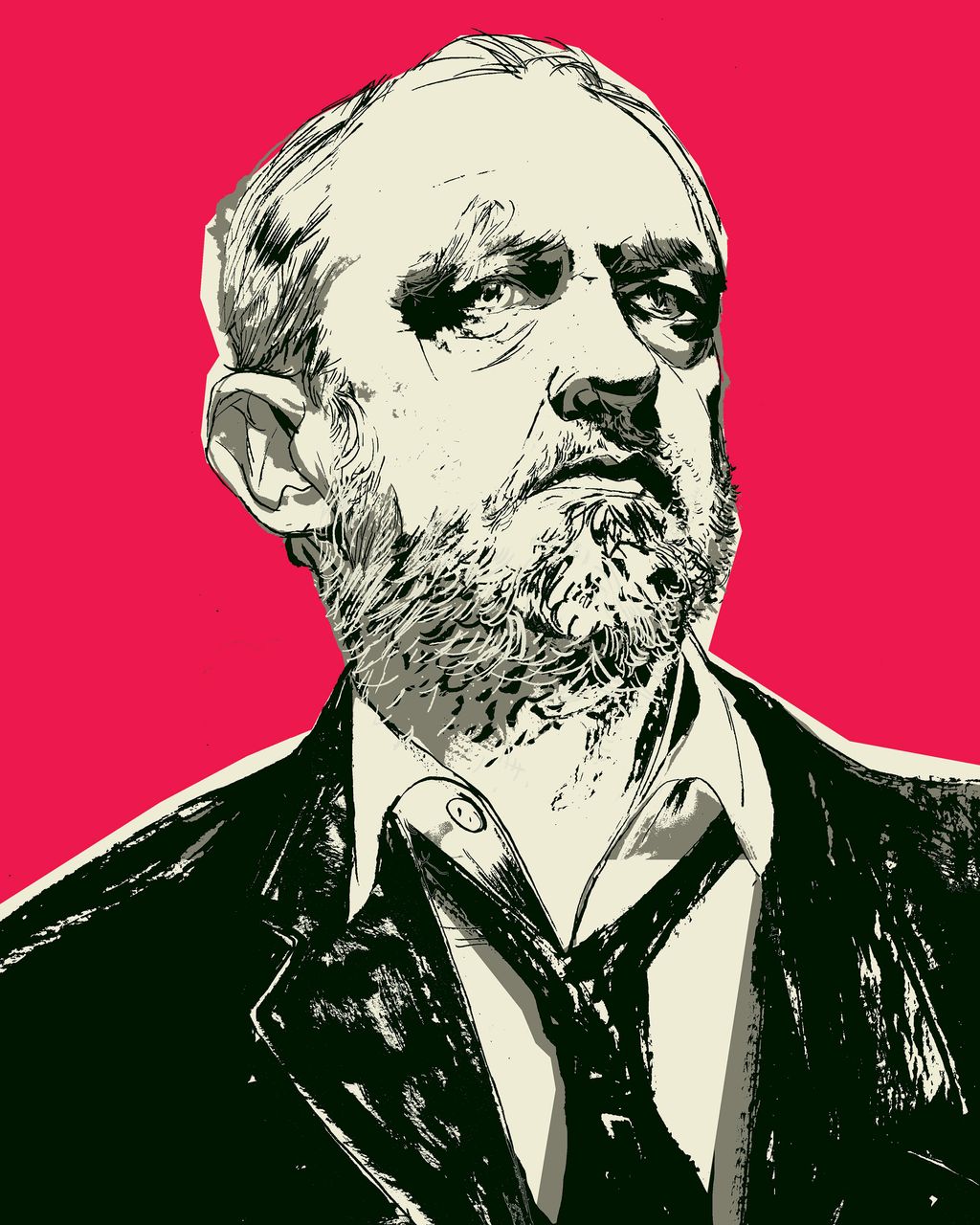

At the center of this story is a 69-year-old socialist eccentric, Jeremy Corbyn, who never in his life thought he would lead any political party, let alone be credibly tipped to be the next British prime minister. The parallels with Sanders are striking: Both are untouched by the mainstream politics of the past 30 years, both haven’t changed their minds on anything in that time, both are characterologically incapable of following party discipline, both have a political home (Vermont; Islington in London) that is often lampooned as a parody of leftism, and both are political lifers well past retirement age who suddenly became cult figures for voters under 30. But this doesn’t quite capture how marginal Corbyn had long been. The better American analogue to his sudden ascent as Labour Party leader would be Dennis Kucinich beating Clinton in the 2016 primaries in a landslide.

Born into an upper-middle-class family, Corbyn was a classic “red diaper” baby. His parents were socialists, and Yew Tree Manor, the 17th-century house in rural Shropshire he grew up in (which his parents renamed Yew Tree House), was a bohemian, left-leaning, capacious, book-filled salon. As Rosa Prince’s biography Comrade Corbyn details, he rebelled at his high school, joined the Young Socialists at the age of 16, and has told a journalist that his main interests as a teen were “peace issues. Vietnam. Environmental issues.” He graduated with such terrible grades that college was not an option, so he joined Britain’s equivalent of the Peace Corps and decamped to Jamaica for two years, then traveled all over Latin America. Appalled by the rank inequality he saw around him, he radicalized still further, and when he came back to Britain, he moved to multiracial North London, with a heavy immigrant population (today, less than half of those living in his district identify as “white British”). It was as close to the developing world as Britain got. And he felt at home.

Even then, he was an outlier on the left. Sympathetic to the goals of the Irish Republican Army, hostile to the monarchy, supportive of Third World revolutionary movements, campaigning for unilateral nuclear disarmament, the young Corbyn was also opposed to Britain’s membership in NATO and what was to become the European Union, because he despised the American alliance and the EU’s capitalist ambitions. He was ascetic: averse to drink and drugs, a vegetarian, interested in hardly anything but attending meetings, and meetings, and meetings. His first wife left him in part because he was never home, always building the movement; his second because he refused to agree to send their son to a selective high school, rather than to a local one open to all abilities. He was the perpetual organizer, the kind who made sure everyone had a cup of tea before a meeting and for whom no fringe activist group was too small to tend to. Decades later, Corbyn has barely shifted on any of these beliefs — and has only recently agreed to sing the national anthem (he long refused to because it invokes the queen). As Labour leader, though, Corbyn has compromised some: The party’s official position in the Brexit referendum was for remaining, and the party manifesto in 2017 supported NATO. He first became a member of Parliament for Islington North in 1983, at the height of Thatcherism, and has held his seat ever since, his majority increasing in all but two of his seven campaigns. (In 2017, he won with a crushing 73 percent of the vote.) His fierce local support tells you something else about Corbyn. Despite his extreme views, he is, by all accounts, a model in attending to the concerns of his local voters and has made remarkably few political enemies of a personal nature. He’s soft-spoken, sweet, invariably cordial, and even his foes concede his deep personal integrity. When I was in London recently, I spoke with people across the political spectrum, from Blairites to Tories to Corbynistas, and I couldn’t find anyone who disliked him personally. Politically, sure — with venom. But as a human being? No. That’s rare for someone who’s been in Parliament for 35 years.

Despite being deeply hostile to the institution of the monarchy, for example, he gets along very well with the queen herself; at their first meeting, he brought her a gift of his own homemade black-currant jam. And there is a profound Englishness to him that balances his internationalism. When he isn’t politicking, he gardens on the British equivalent of a Victory Garden. He loves animals, particularly pigs. He has a passion for cricket, the football club Arsenal, and railways (he refuses to drive a car for environmental reasons). He also has an obsession with manhole covers and takes photos of them across the country. There’s a touch of Chauncey Gardiner about him. And his frugality is legend. He is the kind of person who, leaving a dinner party, will ask for the leftovers so he can give them to the homeless, as Rosa Prince discovered. In the huge scandal over corrupt expenses for members of Parliament a decade ago, Corbyn was found to be among the most abstemious, with even the Daily Telegraph, which broke the explosive story and is deeply loyal to the Tories, describing him as “an angel.”

Some argue that Corbyn has never altered a single belief because he is simply incapable of it. Others say he isn’t smart or intellectually curious enough. Whatever the reason, his purism is singular. In his decades in Parliament, he voted against his own party when it was in government some 428 times — nearly a record. As an MP, he was always on the outer fringe: an early champion of gay rights, a dedicated backer of the Palestinians. He once invited to the House of Commons “my friends” from Hamas and Hezbollah, as well as leading members of the IRA, in one instance just two weeks after the group almost killed Margaret Thatcher by bombing her hotel in 1984.

He went to Grenada immediately after the U.S. invasion in 1983; he was an early champion of Nelson Mandela’s ANC Party in South Africa; apart from some small U.N. peacekeeping missions, he has opposed every Western military action since the Second World War. His reason for opposing George H.W. Bush’s Desert Storm campaign? “The aim of the war machine of the United States is to maintain a world order dominated by the banks and multinational companies of Europe and North America.” In an interview last year, he declined five times to condemn the IRA. And of course he loathed Tony Blair’s “modernization” of the party — Blair once said to one of Corbyn’s constituents, “Ah, Jeremy. Jeremy hasn’t made the journey.”

For his part, Corbyn considers Blair vulnerable to war-crimes prosecution, given his role in the 2003 Iraq invasion. He sees the West as in part responsible for Putin’s invasion of Crimea, and urged his supporters in 2011 to watch Russia Today: “Free of royal wedding, and more objective on Libya than most.” He has appeared on Iranian state television. He refused to blame the Kremlin for the chemical agent that almost killed one of their defector spies in Salisbury in England earlier this year. Skeptical of the analysis that traced the agent to a sole factory in Russia, he suggested that the British government send the sample to the Kremlin to see if it matched.

So how on Earth did he come to be party leader? It’s a tale of unintended consequences, great timing, and the sheer contingencies of history. Corbyn owes his ascendance in part to his predecessor as leader of the opposition, Ed Miliband, who changed the rules for the Labour-leadership election. Miliband’s reforms, which were supported by Blair loyalists, moved the party to a one-person-one-vote system, which aimed to give more of a say to ordinary party members and substantially reduce the role of members of Parliament, leftist local activists, and the trade unions. The idea was to mimic the Democratic Party primaries and bring more middle-of-the road voters into the Labour Party. Under the new rules, a candidate who had been nominated by a mere 15 percent of parliamentary colleagues could then campaign for the support of party members. It was also decided to set the price of membership at a little more than $4. Blair was thrilled: “It is a long overdue reform that … I should have done myself.” The goal was to crush the far left once and for all.

After Labour again lost the general election in 2015, and the Tories under David Cameron won an outright majority, Miliband quit and a leadership election under the new rules was called. “This is the darkest hour that socialists in Britain have faced since the Attlee government fell in 1951,” a leading leftist lamented. “It looked like the end of everything I ever believed in, the destruction of the political left as a force in this country forever,” recounted another to me recently. Three moderate-left candidates emerged, two women and one man. When members of the far-left faction got together to see if they could find a candidate, nobody wanted the suicide mission; their nominees had been trounced in every leadership election of the past 30 years, and some advised sitting the contest out. In the end, Corbyn was one of the few who hadn’t already run and was willing to give it a go. Most assumed he wouldn’t get 15 percent of his colleagues — 35 MPs — to nominate him.

As the deadline for nominations loomed, Corbyn’s prospects looked grim. A few in the party, including several centrists, took pity on him and made the argument that Corbyn should be included on the ballot simply to widen the debate. An hour before the deadline, Corbyn still had only 26 votes. Several more MPs came in as the minutes ticked by, including a leading Blairite who lamented her impulsive decision afterward, and Corbyn neared the threshold. In the final seconds, Corbyn’s right-hand man, John McDonnell, went down on his knees and begged two ambivalent MPs to back him, and they cracked. Corbyn squeaked onto the ballot with 36 votes. “If we get 20 to 25 percent of the vote, that would be a success, wouldn’t it?” Corbyn told a young supporter at the time, who nonetheless raised his eyebrows at the implausibility of it. The bookies gave him odds of 100 to 1.

And then something remarkable happened. The three other candidates — reeling from a second election loss to the Tories — moved slightly to the right to accommodate what they thought was the national mood, only to realize, in the first debates, they had misjudged their party’s. Liz Kendall, a strong contender, and Andy Burnham, the front-runner, found themselves booed for defending Tory welfare cuts. Meanwhile, the newly minted $4 party members began surging in numbers. At each debate, Corbyn spoke unequivocally for the hard left, as he always had, while the others hemmed and hawed and spun. Many noted that he was the only candidate who sounded like a normal human being, and local Labour Party organizations began to coalesce behind him. It was as if, after three decades of accommodating the right, Labour voters decided to vote with their hearts and not their heads.

In a turn of events rather like the 2016 Republican primaries, when the least mainstream of candidates, Donald Trump, burst out of the starting gates, the first poll of Labour Party members revealed, to everyone’s amazement, that Corbyn was in the lead. And not narrowly: He had 43 percent support, 17 points ahead of his nearest rival! Newspapers, fearing disaster, swiftly editorialized against him, including the Labour-backing Guardian and New Statesman. One exception was the Telegraph, which urged its right-leaning readers to join Labour and vote for Corbyn. The headline read: “How You Can Help Jeremy Corbyn Win — and Destroy the Labour Party.” Then Tony Blair, the most successful Labour leader in history, went in for the kill: “When people say, ‘My heart says I really should be with that politics,’ well, get a transplant.”

Through all this, Corbyn smiled. During the summer campaign, he went to a hundred rallies across the country and found himself mobbed by massive, Trump-size crowds. Labour membership kept growing; in the last 24 hours before the deadline, the website crashed as 167,000 people registered. To give some perspective: The Conservative Party’s entire membership is 124,000. Within weeks, Blair was reduced to whimpering, “The question is: What to do? I don’t know.” In the end, it wasn’t close. Corbyn won with 59 percent of the vote in the first round. There was no need for a second. By the end of the contest, Labour had more paying members than any other party in the West, with half a million in its ranks.

The Labour Party Establishment was gobsmacked. Only 20 of 232 Labour members of Parliament had voted for Corbyn as leader (fewer than the 36 who nominated him), and suspicion simmered after his victory. Then came the Brexit referendum, which many pro-EU Labour MPs felt passionately about. A hefty majority of Labourites who backed staying in the EU wanted to form a united front with other parties to create a bipartisan movement. Instead, Corbyn’s old hostility to the EU won out. Many remainers I spoke to insisted that Corbyn and his closest advisers effectively sabotaged the “remain” campaign and were a decisive factor in Brexit’s success. As Tim Shipman’s peerless account of the referendum, All Out War, revealed, Corbyn declined to appear in public with other party leaders, or even previous Labour leaders like Blair and Gordon Brown; refused to state without reservations that he supported the “remain” campaign; constantly voiced his objections to the EU; declined to make a video of support for it; pulled leading Labour remainers out of media appearances at the last minute; and went on vacation at a critical juncture. It drove his fellow MPs bonkers: While Labour was formally pro-“remain,” it seemed as if their leader couldn’t really give a damn either way.

And, of course, Brexit won. Outraged at Corbyn’s performance, most of his parliamentary front-bench team — those groomed to serve in a future Cabinet — resigned. In a vituperative meeting at Westminster, almost every Labour MP told Corbyn to resign too. They even held a no-confidence vote in his leadership, which Corbyn lost, 172 to 40, an unprecedented revolt that would have been enough to end any previous leader’s position. But Corbyn refused to budge, noting that the election rules meant he could ignore his own parliamentarians, and so they forced a second leadership election to get rid of him. And they failed again. Corbyn appealed to the broader party membership, insisted he had just been given a mandate, and was reelected as leader with 62 percent of the vote, a smidgen more than his first victory. His colleagues, however, remained implacable.

They had some reason to feel bitter. Young, radical Corbynistas, steeped in social media, began a steady and relentless campaign of online abuse against the MPs they considered traitors. A torrent of misogyny, racism, anti-Semitism, and foul-mannered comments rattled the parliamentary party. Corbyn said he opposed it, didn’t do much about it, stayed cordial, kept calm, and clung on. His opponents’ next hope was to force him to resign after what they thought was going to be an inevitable drubbing in the 2017 general election. And, of course, that backfired as well — Corbyn performed far beyond expectations. But the wounds were difficult to heal. Since he became leader, Corbyn has faced 103 resignations from his own parliamentary team — almost half of the Labour members. It makes Trump’s record number of quitters look puny.

When I visited Britain this past spring, I was struck by how deep and bitter the divide within Labour remains. “Yeah, it was real intense. Yeah, really intense, really intense. You know, we all lost friendships,” one Corbynista told me of the leadership campaigns and their aftermath. This was Sanders-versus-Clinton-level animosity, but in a smaller, more concentrated pool. I listened to one Labour moderate after another denounce Corbyn’s politics as “sinister” and “incompetent,” even evil. And I heard Corbyn supporters’ faces grow red and their lips curl whenever I mentioned the dissenters. Each of them insisted I tell no one I’d interviewed them. If Labour’s divisions these past few years are any guide, the Democrats’ internal fight could get brutal by 2020.

The central question, of course, is one Corbyn’s opponents have had a hard time answering. Why was the far left able, in its darkest hour, to take over the Labour Party and then come remarkably close in the general election? Some still argue that it’s a fluke. What won Corbyn the leadership was simply his authenticity, they say, compared with the packaged pols who ran against him. And what gave him his general-election surge, they explain, was one of the worst Tory campaigns in memory, a stiff and incompetent performance by the prime minister, Theresa May, who refused even to debate Corbyn one-on-one. Others claim that Corbyn did well precisely because no one thought he could win and so it was a consequence-free vote. Many pro-EU Tory voters may also have used the occasion to vent against their party leadership and vote Labour as a protest. And perhaps all of these factors played a part.

But what’s also unmissable is how deep a chord Corbyn struck. Like Trump, he was a murder weapon against the elite. More specifically, he was the vessel through which the losers of the neoliberal post-Thatcher consensus expressed their long-suppressed rage. And the anger is not hard to understand. There’s no question that, since Thatcher, Britain has regained its economic edge. Its economy for quite a while outperformed those of its European partners, unemployment was relatively low, and London transformed from a dreary city into a global capital. But at the same time, most public- and private-sector wages were stagnating badly and economic inequality soared. From 2010 onward, public spending was slashed under a rigorous austerity program. Hikes in college tuition forced a new generation into deeper debt as interest rates on student loans rose to 6 percent and higher. The new jobs that were created were increasingly low-paid and precarious. Imagine the U.S. economy of the past two decades but with serious cuts to entitlements and public spending instead of the 2009 Recovery Act and tax relief.

And at the same time, British voters watched as the global rich, who survived the financial crash with barely a scratch, flooded the property market in London and the Southeast. The poshest parts of central London are today eerily quiet, the houses all owned by absentee Russian oligarchs, Middle Eastern princes, and others for whom London is an occasional playground. In part because of this, and in part because of a surge of immigration, it became close to impossible for anyone of modest means to afford to rent in the capital, let alone get on the escalator of property ownership. This motivated many on the populist right to vote for Brexit — a revolt against international money and cheap imported labor. But it was also the seedling for an uprising on the left more generally.

“My argument is [that neoliberalism] was incredibly successful; it lasted for a very long time, it worked for a lot of people,” Ellie Mae O’Hagan, a young Corbynista journalist, told me in a café just outside the British Library. “And in 2008, it died. But it was so hegemonic and successful that there was no node of power that could really identify that, because they’d all been colonized by it. And so it sort of limped on in this zombified version for like seven years.” O’Hagan is a working-class writer from Wales struggling to make a living in London and drawn to Corbyn because he alone seems immune to the logic of the past quarter-century. “I guess it’s like a Gramscian thing, you know, when he says the old is dying, the new is yet to be born, and now is full of monsters.”

O’Hagan started out supporting a moderate candidate for Labour in the 2015 leadership election, but everyone apart from Corbyn “campaigned in gray. He campaigned in Technicolor, you know? Whatever you think of his politics and his policies, it was a campaign that was alive. It had ideas. It was forward-looking. It seemed to capture something.” The more you talk with these young enthusiasts, the harder it is to dismiss their zeal. Yes, you often hear them mention Antonio Gramsci and Karl Marx and use the term comrade without irony. But their diagnosis of something gone terribly wrong with the distribution of wealth and opportunity is impossible to gainsay.

What undergirded the Corbynista revolt was a sense that capitalism in the past decade had failed on its own terms: It no longer made most people wealthier. Its massive benefits went to the very rich, who also enjoyed a much lower rate of taxation than in the past, leaving almost everyone else untouched. Corbyn’s closest ally in the Labour Party, John McDonnell, put it this way: “I’m honest with people: I’m a Marxist. This is a classic crisis of the economy — a classic capitalist crisis. I’ve been waiting for this for a generation.” And the Corbynite answer to that crisis was socialism. Unabashed, unafraid, unapologetic socialism.

As an electoral strategy, this boldness worked. In last year’s election campaign, Labour began to take off in the polls the moment it published its manifesto for government. Labour would hike taxes on everyone earning over $106,000 a year and take 50 percent from those making more than $160,000; it would levy a financial-transaction tax; it would raise the corporate-tax rate from 19 to 26 percent; it would prohibit government contractors from paying CEOs more than 20 times what their lowest-paid workers earn. Labour would borrow a whopping $326 billion to invest in infrastructure and public services over the next decade, while retaining a balanced budget for day-to-day spending. It would make college free again; provide free meals for all elementary-school students; embark on a huge public-sector house-building campaign; renationalize water utilities, the Royal Mail, and the railways; and increase spending on welfare. And while staying in NATO and keeping Britain’s nuclear bomb, it would “end support for unilateral aggressive wars of intervention.” It was a list of policies almost designed to enrage Tony Blair and eviscerate his legacy.

The fiscal feasibility of this massive tax-borrow-and-spend program is fiercely contested. One meme that came out of the campaign was Labour’s “Magic Money Tree,” which would somehow make fiscal math disappear. But however unrealistic Labour’s plan was, however ludicrous in places, it didn’t seem to matter. As a way to solidify the left’s voting base and to bring new voters into the system among minorities and the young, the manifesto was a masterstroke. The gains Labour made in 2017 came from under-35s, who increased their support for Labour by 20 points in two years, and from minority voters (up by 6 percent). Perhaps most striking — and the reason why the polls got it so wrong — was that these new voters showed up. A staggering 57 percent of 18- and 19-year-olds voted. The legacy of the crash was also hard to miss: Among those who rented their home, Labour led by 23 points; among the poor, by 47 points.

Owen Jones, the first columnist to endorse Corbyn, contrasts Labour with the center-left in Europe in the wake of the 2008 crash: “We were going through the same process as every other social-democrat party, bleeding in every single direction, to the right, to the left, and to civic nationalists, and the Corbyn project stopped us. Without Corbynism, we would now be suffering the same fate as all of our sister parties, every single one of them.” In France, Italy, Germany, Spain, and Greece, the left has indeed fractured, and radical movement parties — like Syriza in Greece or Podemos in Spain — have decimated the old center-left parties. In Britain, in contrast, the far-left movement didn’t challenge the center-left party. It simply took it over.

Part of Corbyn’s success can be attributed to his steadfast role in left-wing movements outside the Labour Party. From anti-austerity campaigns to antiwar rallies, from animal-rights meetings to trade-union festivals, Corbyn had always shown up, and when he won the leadership of Labour, a vast army of previously alienated leftists entered the party. They were often the ones knocking on doors, organizing rallies, fueling social media, engaging students. In the wake of his leadership campaign, Corbyn kept this army engaged and alive within a movement called “Momentum.” But momentum is hard to control, and the image of Corbyn’s leadership has become increasingly shaped by people who have marinated in far-left politics for years and whose views and rhetoric are far from the mainstream. Some of this, especially on social media, has not been pretty.

And it wasn’t long before the hard left’s hostility to Israel was exposed as riddled with anti-Semitism. Corbyn’s longtime position had been to have no enemies to the left, and he has remained remarkably passive in responding to the surge of Jew-baiting. When it emerged that Naz Shah, a new Labour MP, had opined on Facebook before she was elected that Israel should be relocated to the U.S., and former London mayor Ken Livingstone backed her up by arguing that the Nazis initially favored Zionism, Corbyn didn’t make a big fuss. Both were suspended from membership in the party but not expelled. Other anti-Semitic incidents were investigated at a crawling pace. (Livingstone’s case dragged on for two years before he resigned earlier this year.) To defuse the issue, Corbyn ordered an inquiry; when it found no systemic problem in the Labour Party — only a few anti-Semitic incidents — Jewish figures declared it a whitewash. It then emerged that Corbyn himself had subscribed to various pro-Palestinian Facebook groups where rank anti-Semitism flourished. And that he had once defended a mural in East London that portrayed hook-nosed Jews counting money on a table held up by the oppressed masses. He said he hadn’t looked at it closely enough. It also recently came to light that Corbyn had attended a meeting on Holocaust Memorial Day in 2010, called “Never Again for Anyone: Auschwitz to Gaza,” equating Israelis with Nazis.

Earlier this year, Parliament held a debate on the subject, and a few senior Jewish Labour MPs lambasted Corbyn’s leadership. Labour has had an honorable history of support for the Jewish state from the get-go, had been the natural home of most Jewish intellectuals for years, and had always considered anti-Semitism in Britain primarily a right-wing phenomenon (as it still is). But the testimony from the House of Commons revealed how far the party had drifted. Many Momentum activists opposed Zionism in any form, and campaigned against several Jewish MPs not just for their support of Israel but for being Jewish. One member, Ruth Smeeth, was told by a Momentum member: “Hang yourself you vile treacherous Zionist Tory filth, you’re a cancer of humanity … Zionist hag bitch.” One of Corbyn’s appointees had objected to Britain’s ambassador to Israel because he “proclaimed himself to be a Zionist,” whereas he should have had “roots in the UK” so that he “can’t be accused of having Jewish loyalty.”

In April, the Labour MP John Mann, whose grandparents joined the party in 1906 and who chaired an all-party Jewish caucus in the Commons, rose to speak during a debate on the subject: “I didn’t expect, when I took on this voluntary, cross-party role, for my wife to be sent, by a Labour Marxist anti-Semite, a dead bird through the post … [or for her] to be threatened with rape,” he proclaimed. “I’m stopped in the street everywhere I go now, by Jewish people saying to me, very discreetly, ‘I am scared’. ” Corbyn did not stay in the Commons to hear several moving speeches by Jewish Labourites.

In an attempt to clear the air, he visited with the Board of Deputies of British Jews, the country’s leading Jewish group, at the end of April. But his continuing refusal to do much but utter platitudes left them even more enraged. Last month, a distinguished Labour MP, Margaret Hodge, went up to Corbyn in the Commons and called him “an anti-Semite and a racist” to his face. Even now, the Labour Party has refused to endorse the full International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance definition of anti-Semitism. Last month, the three Jewish newspapers in Britain ran identical editorials on their covers, calling a potential Corbyn government “an existential threat” to Jewish life in the U.K.

It turned out to be difficult to propel a new movement of left radicalism without simultaneously tapping into a vein of left extremism. And Corbyn’s closest circle is a fevered and paranoid one. His media adviser, Seumas Milne, a posh Marxist in the classic 1930s Oxbridge mold, was a defender of the Maoist Cultural Revolution in his youth. He was critical to the sabotage of the anti-Brexit campaign, according to Shipman (though Corbyn’s spokesman contests this), and he despises the mainstream media and keeps Corbyn secluded from the press. Milne is by all accounts a personally charming figure, but he also accused the U.S. of provoking the 9/11 attacks, claims the death toll from Stalinism is overblown, and has defended Vladimir Putin, especially during the Ukraine crisis, as less morally compromised than the West.

Another Corbyn aide is Andrew Murray, a longtime member of the Communist Party of Britain until 2016, a defender of Stalinism (yes, actual Stalinism in Russia), and a dogged supporter of the North Korean dictatorship. He’s been dubbed the Steve Bannon of the hard left. John McDonnell, another important figure (and Mao admirer), has openly backed Irish terrorism. In 2003, he said: “It was the bombs and bullets and sacrifice made by the likes of Bobby Sands that brought Britain to the negotiating table. The peace we have now is due to the action of the IRA.” Threatened with expulsion from the party, he apologized and claimed he was merely trying to keep the Republican cause united. He was once asked what single act he would perform if he could go back in time. His reply: “I think I would assassinate Thatcher.” This is the company Corbyn keeps.

The obsession with Thatcher is remarkable, given that she left the political scene in 1990. The Corbynites loathe but also respect her in a way: “She got things done,” one young Corbyn supporter said. And they see our era as kind of a bookend to the late 1970s. Then, the social-democratic model had collapsed into a raw defense of union power against an elected government, had spawned stagflation, and crippled basic services with mass strikes; energy supplies were so devastated that, at one point, Britain had only enough electricity for three working days a week. Today, the Corbynites see Thatcher’s neoliberal legacy in a similar state of collapse and intend to seize the moment the way she did, but in reverse.

And what’s striking about Corbyn’s policies is how 1970s they feel. Higher taxes, huge spending, massive borrowing, nationalization of major industries, workers’ sharing control with the owners of companies: There’s not much here that’s fresh. Labour has very little to say about immigration, apart from a defense of refugees and opposing what it regards as the “scapegoating” of immigrants of color. It argues, without much evidence, that its new version of socialism won’t be as centralized as in the past. It has little to offer on automation, and seems to believe the international markets won’t react negatively to massive borrowing for a planned economy and that “socialism in one country” is still possible — hence its thinly veiled support for Brexit as a proto-socialist experiment.

Is any of this a serious plan for government? Nick Cohen, one of Corbyn’s fiercest critics on the center-left, argues that the Corbynites are fundamentally unserious and describes the team around Corbyn thus: “For them, any enemy of the West is better than no enemy of the West. They will ally with any movement, however misogynist, however homophobic, however racist or anti-Semitic, as long as it’s anti-Western, including movements like Iran’s theocracy … They cannot say clerical fascism and Russian gangsterism are worse than the neoliberal order.” Indeed, it’s hard to find any in Corbyn’s circle saying even a polite word about the West. If Corbyn and his clique come to power, this much is clear: They intend to make the “special relationship” with the United States a dead letter. Corbyn has been to more than half the countries in the world, and though his spokesman claims he has visited the U.S. often, he could only provide two examples: a recent vacation in Southern California and the time Corbyn addressed the mass rally against the Iraq War in 2003. For Corbyn and his closest advisers, America is pretty close to the Great Satan, while Putin’s Russia somehow always gets the benefit of the doubt.

On the surface, Donald Trump and Jeremy Corbyn are polar opposites. One’s a bully; the other is meek. One does nothing but throw rhetorical bombs; the other is so mild-mannered you have to scan acres of statements to find anything that’s viscerally offensive. One is a crude nationalist; the other an internationalist of near-pathological proportions. One has been a crony capitalist; the other a longtime socialist. One has slashed taxes; the other wants to hike them. One is rebuilding a nuclear arsenal; the other wants to abolish his country’s altogether. One wants to punish football players for kneeling during the national anthem; the other has had to be forced to sing his at all.

And yet note the similarities: They’re both supremely comforting figures to their tribes, stroking the erogenous zones of each, speaking less to how their supporters think than how they feel. Both came from nowhere to smash their rivals in parties whose previous leaders had misread the temper of the times. Trump tapped the deep wells of nationalism, paranoia, and xenophobia that have long infected the American right. Corbyn gave leftists a way to wrest themselves free from the neoliberal constraints that the past 40 years had imposed, to make collectivism cool again. Both were instantly demonized by the mainstream media, and both leveraged it into mass support and reached out beyond it. Trump mastered Twitter; Corbyn’s young soldiers weaponized social media to outflank the tabloids. Mass rallies built their momentum, and television news programs flocked to cover the spectacles. And both ran on the simplest of slogans. Trump had “Make America Great Again.” Corbyn had “For the Many, Not the Few.” I see no reason why the Democrats shouldn’t plagiarize it.

In fact, as much as I find Corbyn’s worldview perverse, his collectivism anathema, and his allies sinister, I think Democrats looking for a candidate to run against Trump in 2020 ought to note simply the potency of his message and the sincerity of his faith. The broad strokes of Corbyn’s policy, like Trump’s, are less well-thought-out strategies for a new century than statements of ideological principle and deep emotion. There is no indication that Trump’s trade war or wall will solve any of the core problems of capitalism’s crisis, and the same can be said for a massive tax-borrow-and-spend agenda for the British economy. But the policies themselves are at least addressing the emergent needs and wants of this moment, even if they will doubtless prove unequal to solving them.

And that cannot be said for the tired bromides of the Establishment left and right. Both Corbyn and Trump gave hope to their followers that politics matters again, that questions ruled out of bounds — mass immigration and free trade for Trump, economic inequality and socialism for Corbyn — are once again on the table. They were expressions of an intensifying political disinhibition. And it was their boldness and stark difference from the politicians of their time that made them first completely unimaginable as national leaders and then somehow inevitable.

Last month, Corbyn gave a speech talking up the benefits of Brexit under a Labour government, shifting nationalism leftward, arguing that a cheaper pound could help exporters if the government constructed a national plan for investment. He has picked up Trump-like themes: “A lack of support for manufacturing is sucking the dynamism out of our economy, pay from the pockets of our workers, and any hope of secure, well-paid jobs from a generation of our young people.” Decrying imports from cheap labor, Corbyn has deftly managed to co-opt some of the populist and protectionist themes that have buoyed both Trump and Sanders.

You might think that a focus on economic inequality would split the electorate along class lines. But in the 2017 election, Labour did as well with the metropolitan elites as it did with the working poor. And by relentlessly focusing on capitalism’s crisis, and on class, Corbyn did defuse a major liability for the left. He has, to be sure, conventional, p.c. ideas on race, gender, and sexuality, but they were not central to his campaign, and he’s as consumed with these questions as any member of his generation, which is to say not much. While over half of his future government team are women, the inner circle is dominated by men. Some even used the term brocialist to describe them. But gender politics — even with a female prime minister — are not as fraught in Britain as they are here.

On immigration, Corbyn also lucked out. If the emerging pattern across most countries right now is not left-versus-right but open-versus-closed, and if parties of the open left are therefore vulnerable to being defined as multicultural super-wealthy elitists, Corbyn defuses the critique. He’s a member of no Establishment; has a long record of voting against the EU; and has accepted an end to the free movement of people after Brexit. He could support some immigration restrictions, though he has no target number, but he also has a proud record of defending refugees and migrants and a long-standing commitment to the developing world. His current wife is Mexican. This is how he manages to appeal to the young, multicultural left as well as the traditional northern working-class base. It’s a trick that would be hard to emulate in the U.S., given the Democrats’ reliance on Latino votes, but it should be possible for an American leader of the left to defend the country’s borders, or to say he or she wants to end illegal immigration and actually mean it.

Two years of proof that the populist left can galvanize voters, of course, does not tell us much about its staying power. And in fact, in this year’s local elections in May, Labour did decently but not spectacularly. When a sitting government is as paralyzed as this Tory one, an opposition party should surely have a more commanding lead in the polls than the few-point margin Labour currently enjoys. Nor has Corbyn’s popularity risen as May’s has tanked, as the anti-Semitism scandals seem to have wounded his reputation.

Still, Corbyn’s shocking viability reveals one thing: This moment rewards boldness and political risk. It requires a set of policies that address stagnant wages, economic inequality, and health-care insecurity; and a leader who is sincere, unpackaged, real. The last thing the party needs is calculation, let alone an emphasis on “electability.” These are radical times. The crisis in capitalism has opened up new avenues for politics that were once unthinkable, a fact that the American right has not hesitated to grasp. I can’t say I agree with the positions of Labour, especially in foreign policy, and I suspect its economic policy could be disastrous if combined with an ugly crash out of the EU. But it’s impossible not to see the logic and power behind Labour’s rediscovery of ambitious socialism in the wake of capitalist failure.

The line between radicalism and extremism is fine. Corbyn’s Labour has failed to rein in its bigots and haters and illiberal opportunists. But the success of his broader message has an obvious lesson for the Democrats: Forget the obsession with Trump. Do not make the next elections about him. Simply make the case for a radical break from the recent past, for a new and more ambitious equality. Dare to raise taxes on the wealthy and lower them on the middle class, dare to bring Wall Street to heel, guarantee universal access to health care, rally the next generation, and abandon pretensions to policing the world. And do this with passion and integrity. You may find new voters, young voters, angry voters, previously invisible voters, minority voters, turning up in numbers you never expected. As America’s liberal democracy teeters under a far-right cult, we’ll need every single one of them.

*This article appears in the August 6, 2018, issue of New York Magazine. Subscribe Now!