When Kathryn Montgomery walked into the Digital Kids conference in New York, she didn’t know what to expect. This was 1995 — the internet was new and full of promise. She still believed that access to books and unlimited information could mean a lot for children’s development.

But sitting through presentations on online playgrounds populated by the likes of Chester Cheetah and Ronald McDonald — places where kids could build personal relationships with these corporate mascots — she began to feel panicked. The internet was supposed to be something different, but the ad men from Madison Avenue just saw a new opportunity. They wanted one-to-one advertising and they wanted to target kids.

Montgomery went back to Washington, D.C., and told her husband, Jeff Chester, and the rest of their team at the Center for Media Education about what she’d seen. Right away, they began working on a report that would become Web of Deception, a study that documented the way companies were using websites to target children. They filed a complaint with the Federal Trade Commission and, within two years, the Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act (COPPA) passed through Congress and was signed into law.

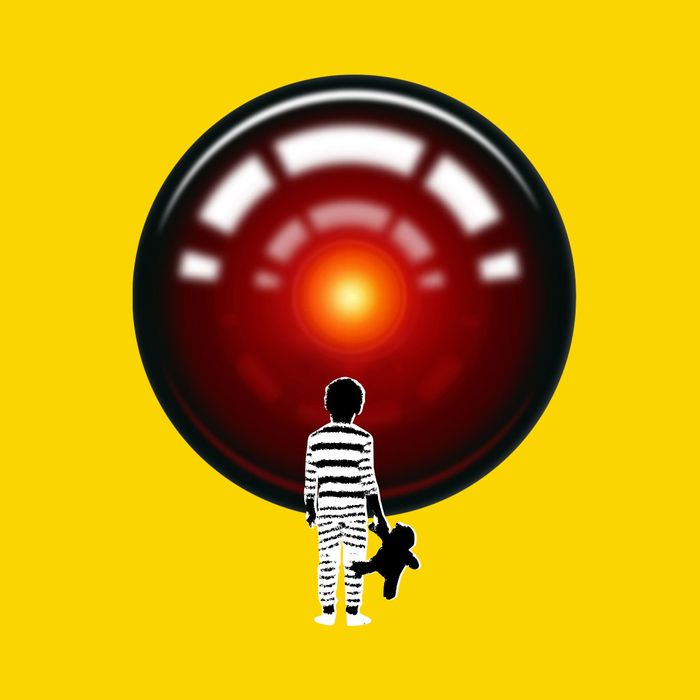

That 1998 legislation, which has been updated by the FTC multiple times since its passage, is still the most stringent internet privacy law on the books. Today, kids under 13 are the only class of American internet user who must opt in rather than opt out of having their data collected. (Children under 13 were identified as a class especially vulnerable to the effect of targeted marketing.) At the time, Chester explained the collection of cookies — small bits of information about a user’s browsing history that travel with that user — as “Orwellian” to the press. Two decades later, the characterization seems quaint. Today, Montgomery and Chester face a much more existential fight for privacy online: the Internet of Things. They’re helping to lead a cadre of activist groups in a battle against some of the largest companies on the planet, and Apple, Google, Amazon, and the rest of the tech world are now entrenched forces in Washington. Chester admits: “We would never have been able to get COPPA through Congress today.”

Even at a time of growing public distrust of social media, consumers are rushing to put the tech industry’s voice-activated devices into their homes. In April, there was reporting about an Amazon patent which posited technology that could eavesdrop on all conversations around Alexa and then send recommendations to users. Though the patent is forward-looking, it led to a news cycle of Big Brother–fueled fear regarding Amazon’s devices. And yet, sales of smart speakers in the United States more than tripled from 2016 to 2017, according to research from the Consumer Technology Association. A Canalys report from January projects 2018 U.S. sales to eclipse 38 million units.

Montgomery remembers the moment she first saw a television — she was four or five and her father lugged it home to set up in the living room. Montgomery and Chester’s daughter, who is in her mid-20s, is of the generation that remembers their first connected device (this writer remembers playing BrickBreaker on his father’s Blackberry at the age of 15). But the next generation will have spoken to a device before they form memories. “When all of this becomes part of the automobile that you drive, the appliances that you use, when it’s all become so much a seamless part of your everyday life,” Montgomery explains, “it will be easy to forget what the potential is of this system to really do harm by invading our privacy.”

The husband-and-wife team believe the moment to regulate privacy in IoT is right now, before everyone has a voice-activated speaker in every room. So the Cambridge Analytica scandal and the subsequent piqued interest in privacy and data protection seemed fortuitously timed for their mission. But seeing senator after senator stumble through their questioning of Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg discouraged the activist couple. “It was embarrassing,” Montgomery says. “And the Internet of Things, of course, is now moving forward so quickly and nobody quite grasps that either.”

It’s instructive to think of Jeff Chester as an Old Testament prophet or Howard Beale from Network. He speaks quickly, rarely finishing his sentences before he’s onto another point. He’s an expert on the internet, and that expertise keeps him perpetually annoyed — from the start, he’s seen the World Wide Web as yet another medium built to sell. By the mid-’90s, Chester began to understand that included in the internet’s business model was the promise of one-to-one marketing. A company could have a personal relationship with consumers by understanding their preferences through data like their browsing tendencies. When he and Montgomery realized internet advertisers were aiming their individualized marketing tools at kids, he became inflamed (which, to be fair, is not a rare state for Chester). “The idea that these companies are designing the products and the services in a way that is gonna take advantage of your child just makes you damn mad!” he told me.

Everyone quickly mentions Chester’s love of confrontation (one person, speaking on his reputation among defense lawyers, put it succinctly: “Jeff is not liked”). Josh Golin, the executive director of Campaign for a Commercial Free Childhood (CCFC), views Chester as a mentor, but that doesn’t mean he hasn’t been on the receiving end of one of Jeff’s blowups. Yet for Golin, the fire is understandable, even laudable. Chester has a rare bird’s-eye view of the industry — his disgust is far from ungrounded. “He really was, for many years, the one doing this work,” Golin says.

In the 1980s, Montgomery was part of a task force in Santa Monica to protect against possible intrusions of privacy via another new medium: cable television. One day, a passionate producer from a radio program came in to interview her colleague, who was charmed by the confrontational, intelligent Brooklynite, so out of place in L.A. “He said, ‘You gotta meet this guy!’” Montgomery remembers, laughing. She finally did meet Chester at a conference at UCLA about satellite legislation (“arcane, wonky policy stuff”) — this summer marks 30 years of marriage.

Montgomery — a Californian, an academic, and a self-described consensus builder — is the perfect yin to Chester’s yang. In 1991, the two co-founded the Center for Media Education (in 2001, their organization became the Center for Digital Democracy (CDD)). Throughout the 1990s, the nonprofit successfully fought on behalf of children’s rights in media — in 1996, they helped secure an FCC mandate that channels show three hours of educational programming for kids each week. But nothing the group has done has come close in scale or prescience to COPPA.

In the late ’90s, there was a whole suite of privacy laws being pushed by activists, but only COPPA made it to President Bill Clinton’s desk. As UC- Berkeley Law professor Chris Hoofnagle explains, while people tussle over the details, there is agreement on the underpinnings of COPPA’s mission: kids should be protected online. (It remains one of the few bipartisan issues in today’s Washington.) But without Montgomery’s spotlight-shining report and without a still fortifying defense from the tech industry, even COPPA wouldn’t have passed into law. It was a marvel of mission and timing. “The industry, the internet, was still in its infancy,” Golin says. Obviously, the same can’t be said for today’s fight.

In May of this year, CDD and CFCC released a joint statement denouncing Amazon’s Echo Dot Kids, an Alexa-enabled device targeted at children. On the same day, two of the groups’ longtime legislative allies, Massachusetts senator Ed Markey and Texas representative Joe Barton, sent a letter asking twelve targeted questions about Amazon’s kids-facing products, specifically around their strategies for securing children’s data and complying with COPPA. Golin’s group had successfully convinced the toy company Mattel to pull Aristotle, a similar voice-activated device, from the market in October of 2017.

But Amazon is not Mattel, so the Alexa for Kids product remains on sale. And in reality, the act of naming a product Echo Dot Kids is actually a self-regulating action by Amazon. COPPA only covers products marketed to children, so the Echo Dot Kids will be required to allow parents to opt in to the collection of their child’s data and will need to delete collected data after a period of time. In reality, many more children are already interacting with Siri, Google Assistant, and Amazon’s adult Echo. (Amazon and Apple declined to comment for the story.)

The process of teaching language to these voice-activated devices is (unsurprisingly) tedious. For Siri, Google Assistant, or Alexa to work, the AI must be able to understand a broad range of languages (Siri can speak 21, while Google Assistant is fluent in 5, and Alexa in 3), but also decipher accents, regional colloquialisms, and differentiate between the speaker and background noise. A Reuters article from March detailed the process that Apple uses to train Siri on a new language. The company brings in voice actors to read passages in a variety of accents, then transcribes the recordings by hand, and then feeds the information, now matched to the script, back into the database. The database continually grows (and is continually transcribed by hand) as bits of recordings from users in the wild are captured and incorporated into the AI. Over time, Siri becomes more and more fluent.

Obviously, teaching AI assistants to understand children is an extra challenge. There is a much higher likelihood of outlier accents and word choice among kids than adults. The task is extra difficult because any collected data of kids under 13 must be discarded every two years under COPPA. So in order to comply with the law, any data collected in the wild and used to train the AI assistants must be specially tagged as belonging to a kid and then scheduled for deletion. Even for parents it’s a challenge to learn to speak fluent 5-year-old; COPPA makes it an extra challenge to teach AI to converse with kids.

A Google spokesperson explained that the Google Assistant has Assistant for Families settings, which minimize data collection and allow a family to teach the Assistant to recognize their child’s voice, which then automatically halts voice-data storage. On top of that, users under 13 must get parental consent to set up an account on the Google voice-activated devices. But for child internet activists, leaving the responsibility with parents rather than the company is still not enough.

As Marc Rotenberg, president of the Electronic Privacy Information Center (EPIC), explains, the system is set up to be difficult for parents to fully understand. He sees most sites’ terms of service as purposefully convoluted (“You can have a Ph.D. in computer science from Stanford and still not understand these things,” he says), and points out that in some cases, agreeing to data collection is the only way to use a website.

He asked me to imagine if the same regulatory structure was used for the auto industry. “It’s absolutely true that before you get in your car, there has to be a sufficient brake pad on the brake lining against the rotor to make sure that your brakes work when they need to,” he says. “But to ask a typical driver to take out a pair of calipers and figure out if their brake lining is at least three millimeters is just nuts. We don’t do it.”

Montgomery’s dream is an FTC with regulatory teeth to force the industry to take a simple stance when creating devices and apps for kids: “First, do no harm.”

The biggest change to Americans’ privacy rights online in years actually comes from across the pond. In late May, the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) went into effect, leading to a wave of emails from companies asking users to consent to new terms of service (and, of course, a wave of memes). The law only protects European citizens, but so far, many American companies working within Europe have widely applied the same stricter privacy practices. The law states that companies must disclose data breaches within 72 hours, allow users access to the data that has been collected on them, and expand the definition of personal data to include browsing history, among other things — the law is enforced with an aggressive fine. For Chester and Montgomery, the GDPR is invigorating, if similar to the suite of privacy laws they fought for in 1998. But they also find it troubling that the E.U. rather than the U.S. government is the one to finally regulate the industry.

Professor Hoofnagle explains that the FTC, which is tasked with all but children’s privacy/data collection enforcement, has institutional wariness against overreach because of a disastrous attempt to curtail ads aimed at kids in the late-’70s. The backlash was so fierce it led to the agency’s temporary dissolution. The argument lodged by opponents of the regulatory effort, dubbed “KidVid,” was that Washington was attempting to create a “Nanny State” — in an editorial from the era, the Washington Post argued, “The proposal, in reality, is designed to protect children from the weakness of their parents.” Shades of the same argument are made today.

Golin and Montgomery both vocalized that it was having kids that humbled them and let them see the impossibility of keeping today’s children away from screens, advertising, and data collection. “It helps clarify your vision of what you think childhood should be,” Golin says.

The Cambridge Analytica scandal has been swallowed up by three or thirty more scandals that have come in its wake. The public’s attention has been aimed in a thousand directions. Facebook stock dipped following congressional hearings regarding its slow response to Russian interference and to fake news, but then fully recovered the $134 billion in lost value within two months. Late last month, the stock collapsed again, losing $119 billion in a single day. But this time investors were punishing the company for focusing too much on eliminating nefarious actors rather than growing the user base. The lesson to tech giants can fairly be understood as: customers will always choose convenience over privacy, and Wall Street would prefer less investment in safety and security.

But Hoofnagle disagrees. The Berkeley Law professor cites a referendum in North Dakota to overturn a 2001 law where banks gained the right to sell personal data. Seventy-two percent of voters said they wanted to protect their private data and overturned the law. And this year, after a California real estate developer became an unlikely privacy activist and managed to gather 600,000 signatures for a GDPR-like ballot referendum, the California legislature scrambled to pass a law to grant Californians far more control over their online data. (The legislature opted for hasty legislation rather a referendum, because referendums can only be amended by subsequent referendums. Some worry the law may be incrementally weakened by the powerful tech lobby in California, which had been expected to spend $100 million to defeat the ballot initiative.) Hoofnagle says that though people desire the convenience of IoT, he doesn’t believe that they disvalue privacy. They just have yet to be given the choice. “I want these tools, you want these tools, everyone wants these tools,” Hoofnagle says. “The question is: on what terms are they offered to you?”

Chester and Montgomery are entering their fourth decade in the fight for children’s rights and privacy. They met over wonky satellite policy, and have fought against the commercialization of cable television and the commercialization of the kid’s section of the internet. Now they’re diving headlong into the battle over the commercialization of kids’ IoT. Chester has mellowed out a bit and Montgomery has gotten a bit more confrontational — but they’re still pissed and passionate and ready for a fight. It’s going to be an uphill battle.