When I first read Alice Walker’s The Color Purple, I leaned into every word, inhaling Celie’s tragic and triumphant story. In Celie, I felt the presence and pain of my female family members brought up in rural Alabama. In Walker’s unflinching descriptions of misogyny, domestic violence, homophobia, and incest, I saw an open accounting of issues buried deep within the larger southern black community — and within my own family.

Above all, I was drawn into The Color Purple because it was haunted by ghosts — the ghosts of Alice Walker’s past. Eloquently and bravely, she was able to confront generational trauma by telling a universal tale that still felt faithful to her own story. And it was Walker’s ability to throw open the shutters and allow her ghosts — our ghosts — into her writing that made it so revelatory. It cemented her standing as an acclaimed novelist, a civil-rights icon, and a formidable thought leader in the field of black feminism.

That changed abruptly two weeks ago, after the New York Times invited Walker to list her favorite books in its weekly “By the Book” column. She took the opportunity to promote David Icke’s And the Truth Shall Set You Free, which contains some of the most hateful anti-Semitic lies ever to be printed between covers. As excerpted in the Washington Post, Icke’s book alleged that a “small Jewish clique” had created the Russian Revolution and both World Wars, and “coldly calculated” the Holocaust to boot. Icke has also accused Jews (among others) of being alien lizard people. After a week of criticism, Walker doubled down in her assessment of Icke’s indefensible work, calling him “brave” and dismissing charges of anti-Semitism as an attack on the pro-Palestinian cause.

It’s chilling to think that such an acclaimed novelist could regard Icke’s work as “a curious person’s dream come true,” but it turned out that Walker’s endorsement wasn’t an isolated deviation. Readers soon unearthed her poem “It Is Our (Frightful) Duty to Study the Talmud,” published on her website in 2017, which confirmed that Walker had been indulging in virulent anti-Semitism, and that it permeated not just her thinking but her work.

The ghosts in The Color Purple helped me to better understand my own identity and the suppressed history of my ancestors — a journey I’m constantly engaged in as a black Jewish woman. But the ghosts in “It Is Our (Frightful) Duty” leave me with more questions than answers. How did Walker’s curiosity curdle into paranoia? How was her commitment to improving the human condition twisted into support for genocide apologists? How could the artist who helped America to better understand black women use her writing to promote the oppression of another group?

In her essay, “The Black Writer and the Southern Experience,” Walker writes that “an extreme negative emotion held against other human beings for reasons they do not control can be blinding. Blindness about other human beings, especially for a writer, is equivalent to death.” Lately it seems that Walker has willingly allowed herself to be blinded. “It Is Our (Frightful) Duty” is a terribly written poem filled with terrible things. It oozes deep paranoia, defensiveness, and rage. In every single way, it’s ugly.

The “poem” utterly fails as poetry. It isn’t lyrical. Its lines and stanzas are choppy and graceless. Each stanza seems to end with an aggressive exhale, the kind that a person expels when they finish purging the awful thoughts that consume them. In some places, it reads like a rambling lecture delivered by a tenured professor who isn’t afraid to offend her students anymore. At other times, it reads like a Breitbart article with line breaks. There is no artistry here, but there is plenty of trauma.

Walker writes that we must examine the “root” of our broken world. For her, the rabbinical commentaries in the Talmud are this root. She claims that the Talmud has provided justification for Jews making slaves of goyim (non-Jews), which world history proves to be untrue. She also claims that the Talmud permits the rape of young boys and 3-year-olds, which is a misinterpretation often used to justify anti-Semitism. Walker is unequivocally wrong about the root of the world’s evil. But how should we begin to search for the root of Walker’s hatred? What ghosts lurk within her stanzas?

I have a deep abiding love for black women and all that we do. Because of that love, I feel betrayed by Walker, and like all scorned lovers, I find myself consumed with a need to understand why. Guided by a singular question (What the fuck happened?), I spent Christmas buried in her writings, trying to understand how Walker could turn on women like me.

The opening of the poem speaks of a male friend, a “Jewish soul,” who accused Walker of anti-Semitism because she didn’t support the state of Israel. Walker refers to this anonymous friend with a great deal of intimacy; charged with anti-Semitism, she herself reacts like a lover betrayed. When she mentions the house that they shared in Mississippi — “where black people often assumed he was a racist” — it becomes clear that she is referring to her ex-husband.

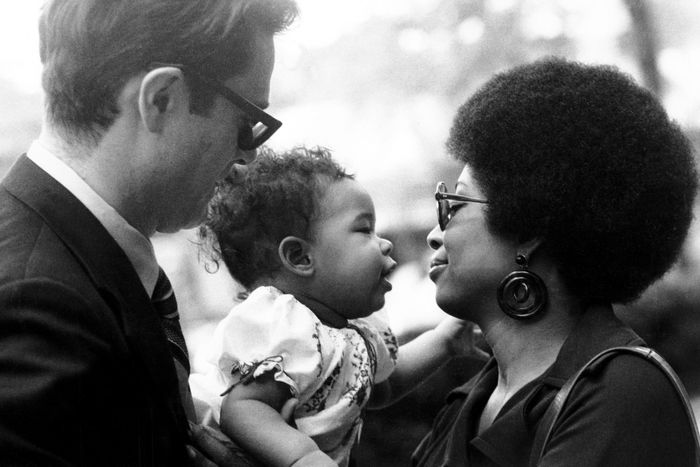

In 1967, Alice Walker married a young Jewish civil-rights lawyer named Mel Leventhal. Their interracial marriage — the first such legal union in the state of Mississippi — was still illegal in Walker’s home state of Georgia at the time. Leventhal’s mother was also deeply opposed to the union, and his other family members didn’t allow Alice to attend family events. “Leaving no question about how she felt about her son’s marriage to a shvartse (a pejorative Yiddish term for a black person), Miriam Leventhal sat shiva for her son, mourning him as dead,” Evelyn White writes in Alice Walker: A Life. A source who knows the family told me that Mel preferred to ignore rather than confront his family’s bigotry. This caused Walker to feel increasingly isolated and resentful. The marriage ended in 1976, after the pair had one daughter together, named Rebecca.

When writing of Mel in her essays, Walker links him inextricably to his Jewishness, as well as his occupation as a lawyer. Even when they are not arguing (frequently, according to her) about the abuses against Palestinians, each mention of him is some variation on “white Jewish lawyer husband.” Perhaps Walker is combining those disparate words — each a piece of his identity, yet each reductive — to make sense of his contradictions: How could he fight for the dignity of black people while allowing his white family to deny dignity to his wife and daughter? How could he be white, and yet not fully welcomed by white gentiles in Mississippi? How could he crusade for justice at home and dismiss her concern for Palestinians abroad?

I loathe the misogynist assumption that a woman’s faults must be the direct result of a man’s actions, but I find myself incapable of separating Walker’s fraught marriage from her hatred of Judaism. She doesn’t separate the two either. In her 2014 book, The Cushion in the Road, Walker writes about meeting an elderly Palestinian woman in the Occupied Territories. The woman accepted a gift from Walker, and then bestowed a blessing upon her, “May God protect you from the Jews,” to which Walker responded, “It’s too late, I already married one.”

It’s telling that Walker feels she should reference her marital strife in such a context, even as a joke. In both this comment and in her poem, she seems incapable of reconciling the conflicts inherent to Leventhal’s identity — conflicts that put a strain on their marriage. Instead of accepting that white Jews can both oppress and be oppressed, Walker leaps to blaming all Jews (and the Talmud) for all oppression.

Walker writes in the poem of trying to educate the “Jewish soul” on the topics of “dignity,” “justice,” “honor,” and “peace.” She sets off each of these words with quotation marks, casting doubt on whether Jews are capable of learning these values. Walker is quite proud of her subsequent epiphany, insinuating that those (like her younger self) who believe that any Jew can desire peace, justice, and honor know “Nothing. Nothing at all.”

Walker’s fights with Leventhal are not the only ghosts in this poem. There is also Rebecca Walker, Alice’s daughter. Rebecca and Alice haven’t spoken in many years, and Rebecca has publicly denounced her mother for being neglectful during Rebecca’s childhood. “I came very low down in her priorities,” Rebecca wrote in 2008, “after work, political integrity, self-fulfillment, friendships, spiritual life, fame and travel.”

While Rebecca never addressed her mother’s anti-Semitism, she is known for publicly embracing her Jewish identity, most notably in her book Black, White, and Jewish. How must Rebecca be feeling right now? How would it feel to have the whole world discussing your mother’s hatred of your Jewish soul, your religious texts, your heritage?

As a black Jewish woman, I find the white Jewish community’s focus on black anti-Semitism hypocritical and distracting. Its negative impact is often exaggerated, and dwelling on it is counterproductive to racial justice and solidarity. But in an attempt to show compassion toward black people — especially black women — I sometimes find myself burying my own opinions about it at the expense of my soul. Recently, I was at an event where someone implied that Jews were naturally more conniving and exploitative. I shut down the conversation, but I wanted to flip the table in anger. What does that do to the soul of the black Jewish woman, who is often rejected by both the white Jewish community and — more rarely — by the sisters who are supposed to understand her?

In an interview for the PBS documentary “Alice Walker: Beauty in Truth,” Walker said she was hurt and confused by her estrangement with her daughter. “You bring children into the world. You love them with heart and soul,” she said. “But, as (author) Tillie Olsen told me, ‘You have your own children and do the best you can until they are able to get out in the world. And then the world takes over.’”

In the poem, Walker invokes her maternal status as a source of her authority over all of humanity. She refers to herself as an “elder” who went to Palestine to “do my job / of keeping tabs / on Earth’s children.” It’s a particularly defensive stanza in an already-paranoid poem. I feel that she is trying to convince herself that she has done her job as an actual mother. Her claim on the “Earth’s children” reads like a deflection from the one child she has, who is surely bothered by her mother’s hatred of Jews like herself.

Another source of the poem’s purported authority is age. Walker tells us that we will understand the evils of the Talmud as we get older. “We must go back / as grown-ups now, / Not as the gullible children we once were … It is our duty, I believe, to study the Talmud.” But Walker isn’t talking to us. It feels like a plea to her child. A plea for what? Understanding? Forgiveness? Permission?

I can understand Walker’s trauma: I live much of it. But I cannot understand how she could write such awful things. I understand that Walker experienced virulent anti-blackness from many in the white Jewish community — as I have — but I don’t understand how she could spin that off into a hateful conspiracy. I don’t understand why this poem was written. But I do understand that everything about it paints a picture of heartbreak. I see a person who has made terrible mistakes, and who is desperately trying to run away from them. I may not be able to forgive or excuse, but it is my frightful duty — as a black Jewish woman — to try to understand.

I spoke to a black Jewish woman who said that Alice Walker’s anti-Semitic “trolling” needed to be called out, but also that Walker was “a monster of [the white Jewish community’s] own making.” She warned that a failure to address such racism would push more people — notably, Jews of color — to this extreme. I believe this; I’ve already reported on the ways that racism was pushing black Jews away from the community. The impact of this dynamic on Walker’s work is supported by her description of her writing process in the essay “From an Interview”:

“All of my poems … are written when I have successfully pulled myself out of a completely numbing despair … Poems — even happy ones — emerge from an accumulation of sadness … I become aware that I am controlled by [the poems], not the other way around. I realize that when I am writing poetry, I am so high as to feel invisible, and in that condition it is possible to write almost anything.”

Still, I wonder how Walker could put the burden of her trauma onto us — black Jewish women. What is her responsibility to her daughter, and what is my responsibility to Alice Walker? Many of my black and Jewish friends refuse to even judge her. Perhaps it is I who know nothing, nothing at all.

I know that I will not cancel Alice Walker. I can’t erase the incredible work she created. I will continue to read The Color Purple and her other works. But I will never be able to rid myself of the ghost of this poem. It would be irresponsible and self-hating of me to do so. I will read and teach Walker’s work with love, but this poem will always be there, fluttering in the wind like a torn-out page of the Talmud.