From roughly 2007 until 2013, the smartphone market grew at an astonishing pace, posting double-digit growth year after year, even during a global recession. They were the good years, the type that would inspire a Scorsese montage: millions and then billions of smartphones going out; billions and then trillions of dollars in rising company valuations; every year new models of phones hitting the market, held up triumphantly at events that were part sales pitch, part tent revival. (To nail the Scorsese effect, imagine “Jumpin’ Jack Flash” playing while you think about it.)

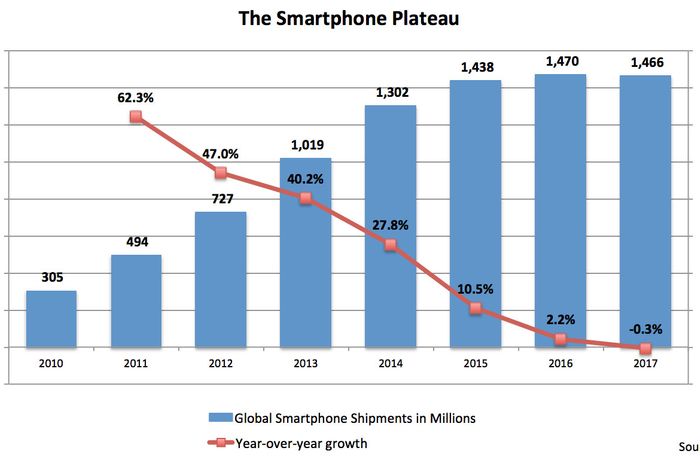

But just like every Scorsese movie, the party ends. Smartphone growth began to slow starting in 2013 or 2014. In 2016, it was suddenly in the single digits, and in 2017 global smartphone shipments, for the first time, actually declined — fewer smartphones were sold than in 2017 than in 2016.

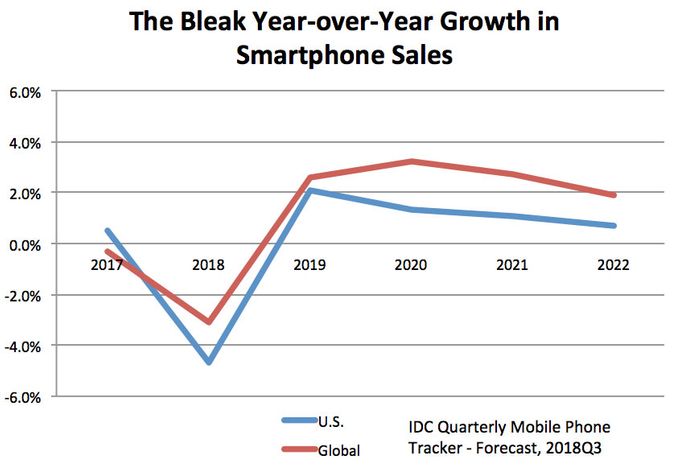

Every smartphone manufacturer is now facing a world where, at best, they can hope for single-digit growth in smartphone sales — and many seem to be preparing for a world where they face declines.

The Smartphone Plateau

The idea of a “smartphone plateau” has been floating around since at least 2012, with the phrase entering common usage in the middle of this decade. It has a twofold meaning. One is the slowdown in smartphone innovation, which was once progressing at that same breakneck pace as smartphone sales. If you bought a new iPhone 3G in 2008, and then a new iPhone 4 in 2010, you were buying markedly different machines, with the iPhone 4 sporting a Retina display, a much better battery, a faster processor, and a sleek, sharp-edged design. If you bought an iPhone 6 in 2014 and then an iPhone 7 in 2016, that expected improvement was much harder to mark (except, perhaps for that fact the the iPhone 7 didn’t have a 3.5mm headphone jack). The other meaning is the flattening of smartphone sales.

We’re already fairly far along this plateau — from 2015 to 2017, global smartphone shipments have held firm at about 1.4 billion per year — but talking to analysts and reading the tea leaves of what the major manufacturers are doing, it’s looking like we’re reaching the end. Not because sales are picking up again, but because we’re heading toward the downslope. “I think we’re well over the plateau,” says Ben Stanton, senior analyst at Canalys. “We’ll see little pockets of growth in the global market, but on the whole it’s a declining picture.”

In 2017, per the International Data Corporation, global shipments of smartphones declined year-over-year for the first time in history. In 2018, IDC says the same thing happened in the U.S. market. “We are at market saturation rates of 90 to 100 percent in many developed markets,” says Ryan Reith, program vice-president at IDC.

Some manufacturers and analysts may hope that flat sales in the developed world could be offset by strong sales in other markets. Fat chance. The markets where smartphone saturation hasn’t set in yet — such as India, Southeast Asia, pockets of Latin America, and Africa — are different than the markets that fueled the first decade of smartphone growth. “In those markets, there are extremely competitive devices down near the equivalent of $200,” says Stanton. “It’s becoming a real battlefield, but it’s a low-margin business and consumers down at the those price points tend to be not very brand-centric. That really plays into hands of a few really hyperaggressive brands of smartphones, most of which are coming from China.”

The Artificial Replacement Cycle

If you’ve bought flagship phone in this year, you likely won’t need to buy a replacement until the next decade. “Most people have more phone than they can handle, or need,” says Gartner senior principal analyst Tuong Nguyen. “It’s similar to what you saw in the PC market for while — people had really powerful PCs but they barely used it for anything. It’s the same with phones.”

Your smartphone camera is good to great, and you mainly share those photos on social media, where photo quality doesn’t matter much anyway. Barring a few high-end 3-D games or technologies like augmented reality, your processor can handle everything you throw at it, and will for a while. Your screen is bright and sharp, and while there may be slightly better screens out there, you’d only be able to tell by holding the two phones side-by-side. Durability has vastly improved; waterproofing is now standard on smartphones, so a brief dip in the sink or toilet doesn’t mean you need a new phone, and the weakest links in smartphone hardware — batteries which tend lose their ability to hold a charge over time and screens that crack and shatter — have improved.

Still, we tend to replace our phone every two years, regardless. A lot of this has to do with how cell phones were sold in the U.S. for a number of years. Carriers signed customers to two-year contracts, and sold phones at a subsidy priced into the contract. Every 18 to 24 months, you’d be able to upgrade to a new phone again. It felt natural, like the change of seasons or the migration of birds. But that cycle was artificial. Even as two-year contracts have died, carriers rarely talk about the flat price of a phone, but instead break that price out over 24 months, making it relatively easy to keep consumers buying high-end phones. A phone that costs an extra $100 total is only about $4 more per month on a financing plan — the price, as the saying goes, of a cup of coffee. “The U.S. operators did a good job working in the transition,” says Reith of IDC. “Even though when you look at it objectively, it got worse for the consumer.”

The results of this are stark. Per IDC, 43 percent of phones sold in the U.S. in 2017 cost over $600 (and 19 percent of those cost more than $800). Another 40 percent of phones sold cost less than $200, nearly all of those prepaid phones sold through vendors like MetroPCS. Just 15 percent of phones sold cost between $200 and $600 dollars. “The middle price band is nonexistent,” says Reith. The current U.S. cell phone market could be compared to an auto market in which the majority of consumers either bought a Mercedes or a Kia, and brands like Honda essentially didn’t exist.

Despite all this, there’s no doubt that the replacement cycle for phones is elongating. “Over the last five years, the replacement cycles of smartphones in the U.S. has has increased from an average of 20.6 to 24.1 months,” says Jennifer Chan, global insight director at Kantar. More worrying for smartphone manufacturers is that desire for new technology doesn’t really spur consumers to buy new phones. “The number-one purchase trigger is ‘My last device was broken,’ and this has increased year on year,” says Chan. “Triggers like ‘I just wanted a newer model’ and ‘I had the option to upgrade early’ have declined or remained flat.”

Trying to Delay Commoditization

As the market reaches maturity, smartphones are verging on becoming a commodity — a fate the major smartphone manufacturers like Samsung and Apple desperately want to avoid.

“Commoditization is the normal cycle for most products,” says Willy Shih, a professor of management practice at Harvard Business School. “When the first Xerox plain-paper copier came out, they were really cool and Xerox became a fabulously successful company. But then their patents expired, and other companies like Canon came in and introduced low-cost office copiers. Now, copier machines are a dirt-order commodity.” Think very hard about your own office — can you name the brand of your office copier?

Or take televisions, another commodity where consumers show little brand loyalty, allowing for upstarts like Vizio, TLC, and Hisense to strip market share away from established players like Sony or Panasonic — which, of course, had displaced established players in television like Magnavox or RCA.

“Once you get driven into the commodity space, you start to think, ‘Oh, I’ve just got gotta come up with the next great feature that will cause people to buy my product over the others,’” says Shih. “But at some point, you way exceed what consumers need or are willing to pay for. And then you become a commodity.”

Samsung is in the most danger of this happening. While the brand has loyalists to its Galaxy S and Galaxy Note series of phones, Samsung phones are, at the end of day, Android devices. And there are signs that desperation is starting to set in. The company plans to release a foldable phone this spring, possibly called the Galaxy Fold, with use case that’s hard to discern and a price point rumored to be $2,000. It’s the type of desperation move you saw from TV manufacturers in the beginning of the decade, where they hoped that first 3-D televisions and then curved TV sets would spur consumers to spend more. Both strategies failed for television manufacturers, and it seems likely that Samsung’s foldable won’t end up being much more than a tech curio.

Meanwhile, Samsung may be losing the battle in low-cost global markets. “Samsung has been quite arrogant in the past 18 months,” says Canalys senior analyst Ben Stanton. “They believe their brand is strong enough to offset the impact of commoditization, and that has proved not to be the case if you look at the rapid expansion of [Chinese brands] across India, Africa, Southeast Asia, and Latin America.” These brands may be unfamiliar to American consumers — Xiaomi, Oppo, Vivo, and Transsion are all major players — but if there are countries where double-digit growth is still possible, it will likely be these companies that enjoy it.

How Long Can Apple Defy Gravity?

While the rest of the smartphone market worries about commodification and what each brand will need to do to gain or defend market share in a world where smartphones are like cars, Apple stands alone. “Apple has a different set of options available to it,” says David Yoffie, a professor of international business at Harvard Business School who also sits on the board of HTC. “They have this extraordinary user base that allows them to do things other firms could never get away with.”

The iPhone is uniquely positioned in two ways, one that works for it and one that works against it. In markets like the U.S. or some European countries, where the iPhone enjoys significant market share, iOS and its ecosystem are a true differentiator. If you want a phone that can use Messages and avoid the dreaded green bubble when texting people, there’s only one manufacturer available: Apple. The same goes if you want to use a HomePod or an Apple TV, or want a phone that integrates easily with your MacBook.

But globally, iOS isn’t as attractive. In the Chinese market, an app called WeChat is practically an operating system unto itself, allowing users to do everything from message someone else to pay their electrical bill or order food. And WeChat runs equally well on Android or iOS, meaning the iPhone has consistently struggled to find a foothold in the Chinese marketplace. In other markets, messaging apps like WhatsApp are dominant, and phone price is much more of a concern. The results are stark. In the U.S., about 40 percent of phones run iOS. Globally, that number is just 14 percent.

Still, Apple has a firm grip on a large and affluent share of the U.S. market, and Tim Cook and his executive team have a clearly developed long-term strategy to deal with a world where people buy fewer phones: Make the phones themselves more expensive (thus the iPhone X at $999, followed by the iPhone XS Max at $1,099), and attempt to boost services revenue (everything from Apple Music to iCloud storage to Apple Pay to the 30 percent Apple rakes in from any App Store purchase) as quickly as possible, with the goal of bringing in $20 billion a year by 2020.

But its strategy of slowly raising its average selling price while selling fewer phones has a natural limit. “That’s a dangerous path,” says Shih, “because when you lose the volume, then you lose a lot of the manufacturing efficiencies and some of the cost benefits.” Moreover, for Apple to be successful in replacing lost revenue with its services division, it still needs a large number of iOS users. Raising the average selling price is effective in the short term, but may backfire in the long term. “Apple will exhaust that strategy,” says Yoffie. “When Apple is at an average selling price of $800, and the rest of industry is at $300, you can only defy gravity for so long.”

There are already signs of investor worry. Apple surprised everyone during its earnings call in early November when it announced it would no longer release how many phones it sold each quarter. This news was taken as tacit acknowledgment by Apple that it doesn’t anticipate ever selling more phones than it sold in a previous year, and its stock price plummeted since, taking the company’s valuation back below a trillion dollars, part of the overall slump in tech stocks that has acted as a major drag on the stock market overall.

It’s a good reminder of just how large the smartphone market is overall — global smartphone sales accounted for nearly $500 billion in revenue in 2017, and there are a host of ancillary businesses built out to support that market, from companies in the supply chain to operations that make smartphone cases. If we truly are entering a period of declining smartphone sales, the ripples of that decline will be felt on many shores.

Your Phone Is a Car Now

But what [local newscaster voice] does this mean for you?

With phones that are more reliable, have fewer changes every year, and are increasingly expensive, you should treat your phone like a car. If some jerk clips off your side-view mirror while you’re parked and doesn’t leave a note, you don’t trash your car and get a new one — you get a new side-view mirror. If you crack your phone’s screen, don’t get a new phone, get a new screen.

And when your phone truly does run its course, whether because you simply want something newer and faster, or your old phone has finally stopped working, consider avoiding the newest phone on the market. Relatively few people buy new cars, because it doesn’t make much sense financially. Instead, most people, even those with who could buy new, buy a used car.

This doesn’t mean turning to the secondhand market for smartphones, which is still developing and prone to problems (though it’s not impossible to see that market grow more over the next decade). Instead, consider buying a smartphone one year behind the newest model. A Google Pixel 3 is a fantastic phone that sells, as of this writing, for $799. A Google Pixel 2 is also an extremely good phone with slightly fewer features, and sells for $649. One year, $150 less for a phone that, unless you are a true gadget nerd, you will not notice much of a difference. The iPhone market follows much of the same rules — the iPhone XR, the cheapest phone Apple released this year, is a fantastic phone that costs $749. The iPhone 8, still a superb machine, can be had for $599.

Looking forward, there is no device that seems poised to replace the smartphone as the machine at the center of most of our digital lives. The wearables seem to be a niche market at best, smart speakers will likely remain only in our homes, and something like always-on wearable AR is decades away from being a reality. For consumers, this means a world where you hold on to your phone for longer and longer, which is good for your pocketbook and good for the environment.

For manufacturers, the next decade will likely be a great shakeout, with some old guard names leaving the market, some newer brands becoming ascendant, and the winners acquiring and stripping the losers for parts. But manufacturer loss is consumer gain; the main differentiator in a mature market where commoditization has fully taken hold is one that should be appealing to anyone who shops for a smartphone: price. Behind the scenes there may be a bloodbath, but you’ll simply notice that you’re getting a lot more phone for a lot less money.