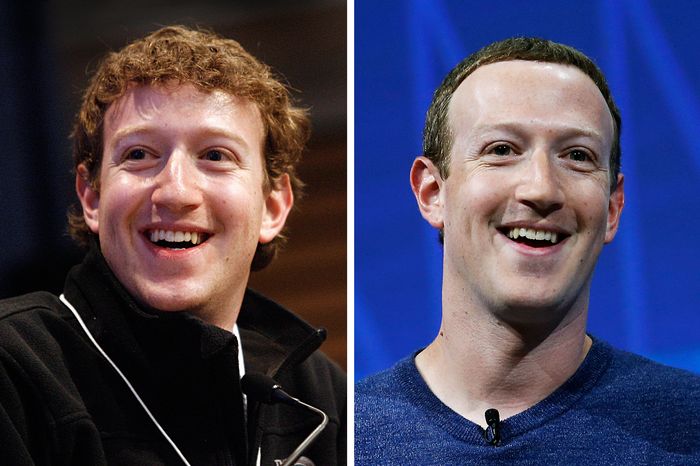

As memes go, there’s very little to complain about with the “2009/2019” (also known as “2009 vs. 2019” and “10 Year Challenge”) meme currently sweeping Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram. All you do is post a picture of yourself in 2009 side by side with a picture of yourself taken this year. It’s easy! It’s wholesome! It’s a good setup for a joke! It’s a memento mori! It’s also, maybe … a conspiracy?

In Wired, Kate O’Neill makes the case that we should be suspicious of the meme, because we’re (in effect) creating a large, rich, and completely free data set for machine learning:

Imagine that you wanted to train a facial recognition algorithm on age-related characteristics, and, more specifically, on age progression (e.g. how people are likely to look as they get older). Ideally, you’d want a broad and rigorous data set with lots of people’s pictures. It would help if you knew they were taken a fixed number of years apart—say, 10 years. […] Thanks to this meme, there’s now a very large data set of carefully curated photos of people from roughly 10 years ago and now.

The idea that the #10YearChallenge might be a shady astroturfed meme intended to capture innocent user data isn’t so extraordinary, as far as social-media folklore goes. There’s a widely held conspiracy theory that Facebook is eavesdropping on conversations through our smartphones — how else, the idea goes, could Facebook serve up advertisements about things I was literally just talking about? (Facebook has always unequivocally denied that it does, and given how the microphone in your iPhone works, it’s highly unlikely that it would even be capable of doing so.) But as an excellent episode of the podcast Reply All, exploring the conspiracy theory, explains (not entirely to the satisfaction of most listeners) Facebook doesn’t need to eavesdrop on you: The data it already has and is able to extract continuously — from your use of its apps, from your browsing habits off of Facebook, and from third-party data brokers monitoring things like your use of credit cards — is more than enough for it to target you with ads and recommendations with uncanny accuracy.

The same is true of conspiratorial thinking around the #10YearChallenge meme. Just as Facebook doesn’t need to eavesdrop on you, no one needs to fool you into posting photos of yourself. Indeed, as O’Neill herself acknowledges, there is already a particularly large data set of carefully curated photos of people from roughly ten years ago and now. It’s called “Facebook,” and I personally have been a longtime volunteer, donor, and subject. If you’re one of the 350 million people or so who’s been on Facebook since 2009 — or if you’ve uploaded older photos to the platform after joining — the world’s biggest social network already knows what you look like now, in the past, and probably in the future, too. O’Neill argues your already-extant Facebook photos aren’t as useful a data set for training facial-recognition algorithms as the 2009/2019 photos, but that seems obviously untrue: Facebook has spookily sophisticated face-recognition technology, as anyone who’s seen Facebook’s automatic tagging software at work will tell you.

The truth is that there are dozens of large, publicly available data sets that can be used to train facial-recognition algorithms. Granted, none are as large or as rich as Facebook’s, but they’re more than enough for most people and companies’ non-world-conquering ambitions. If I were going to build a conspiracy theory around the meme, I might suggest that it was planted by a social network, not as a way to secretly extract data, but as a way to secretly drive engagement. The world is rich in available data — most of it given freely without even the need for a dastardly meme conspiracy theory — and much poorer in attention span. The time a person spends on a site uploading a photo for a meme is likely much more directly valuable to the site than the data from the photo would be. (Though, of course, they’ll be all too happy to hang on to the data in the hopes it can eventually be put to profitable use further down the line.)

In any event, O’Neil isn’t suggesting that Facebook or some other shadowy third party is actually behind the 2009/2019 meme. She’s arguing more simply that the ready-made, potentially exploitable data set created by the meme is a reminder that “we must all become savvier about the data we create and share, the access we grant to it, and the implications for its use.” It’s hard to disagree with the idea in principle: We should choose cautiously when, where, and how we share our data if we don’t want information about us to be misused or abused.

But … when do we get to choose, exactly? The breathtaking scope of contemporary surveillance and data-extraction processes doesn’t just make conspiracy theories about astroturfed memes and bugged smartphones seem almost pathetic in comparison. It also reveals how little our own choices are able to control the flow of our data, and how little our knowledge really matters. I might be aware that photos of myself in 2009 could be misused, and choose not to participate in that meme. But simply by living a fairly regular life on and offline — by clicking on links and writing posts; by opening Instagram and scrolling through it, hovering over some photos and flicking past others; by using credit cards at chain stores; by letting photographs of myself be taken and uploaded to the internet — I’m generating data that’s probably more valuable to the companies involved than those photographs would be. There’s something tragic about the fact that the purely recreational activity of participating in a meme is the subject of conspiratorial paranoia, while the multitude of chore-like activities we do daily, from which data is also being extracted for hoarding or sale, go mostly ignored.

None of which is to suggest that it’s a waste of time to be prudent about data exposure, or that we shouldn’t expect the worst from the platforms and brokers watching us online. Just that mere prudence (or mere paranoia) isn’t sufficient to protect data about you from being gathered, or being abused. Data extraction for profit is neither a conspiracy, nor a problem of individual inattention. It doesn’t need to be — it’s the way the internet of this era works. And any solution will have to come at a similar scale.