The year 2019 marks a sea change in American politics. More than 100 new members of Congress were sworn in on Capitol Hill on Thursday, including 67 freshman Democratic representatives, introducing President Donald Trump to divided government for the first time in his tenure. The new House majority will seek to obstruct key parts of his agenda, most immediately by refusing funds for his U.S.-Mexico border wall. Just as Trump’s election in 2016 was seen as a rebuke of the Obama era, the blue wave that engulfed the November midterms can be understood as rejecting his first two years in office and curbing his heretofore unchecked power.

But locally, a different sea change has been underway for years. Voters dissatisfied with their local prosecutors — who in several high-profile cases have shielded police from accountability by declining to charge them for killing unarmed black boys and men — have sent old officials packing in favor of more reform-minded replacements. New top prosecutors in places like Cook County, Illinois, and Orange and Osceola Counties, Florida, have taken office on vows to curtail their predecessors’ more punitive practices, especially concerning black and brown people. Nowhere was this more apparent than in St. Louis County, Missouri, where former Prosecuting Attorney Robert McCulloch guided a grand jury into declining charges against Ferguson police officer Darren Wilson for killing Michael Brown, a black teenager, in 2014.

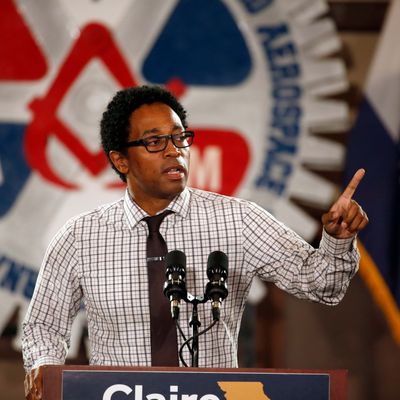

In August, McCulloch was primaried into early retirement by Wesley Bell, a fellow Democrat and black former Ferguson city councilman. Bell ran on a reformist platform that included ending cash bail and the death penalty, and “[resisting] the Trump administration” by limiting local cooperation with federal immigration authorities. Since his swearing in on Tuesday, he has wasted little time demonstrating his intentions to fulfill his promise to “fundamentally change the culture” of the office that his predecessor held for 27 years. On Wednesday, he suspended two McColluch-era veterans, Ed McSweeney and Jennifer Coffin, pending termination hearings, according to the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. He also fired Kathi Alizadeh, the main prosecutor who presented evidence to the Wilson grand jury, and who famously submitted to jurors an old statute asserting that police are justified in killing unarmed suspects who flee the scene of a felony. The statute had been ruled unconstitutional in 1985. “Despite Mr. Bell’s rhetoric about building bridges with career prosecutors, he has apparently decided to suddenly discharge three dedicated public servants in his first hours in office,” Ed Clark, president of the St. Louis Police Officers Association, the union that represents two of the impacted attorneys, said in a press release calling for their reinstatement.

Bell’s shake-up seems practical as well as symbolic. Though the ex-councilman has not made public why he chose to take action against these three prosecutors specifically, McSweeney claims his suspension is retaliation for a Facebook post he wrote criticizing the incoming prosecuting attorney. “County voters will soon regret what they did,” McSweeney reportedly wrote after Bell’s victory and McCulloch’s ouster. Alizadeh’s seems more symbolic, given her involvement in the case that threw Ferguson into chaos and cemented its residents’ lack of trust in the prosecutor’s office. But both send a message. The speed and intentionality of Bell’s moves herald his desire to show the public that St. Louis County is entering a new era of criminal justice.

These changes, though significant, are dwarfed by the tragedies that have marked Ferguson these past four years. Brown’s death and the Wilson non-indictment sparked rioting in the St. Louis suburb in August and November 2014, the root causes of which were laid bare in a Department of Justice report published in March 2015. The report found that “Ferguson’s law enforcement practices [were] shaped by the City’s focus on revenue rather than by public safety needs” — which, in turn, drove police to generate funds by stopping, harassing, and ticketing Ferguson’s majority-black citizenry. Municipal courts augmented these efforts by issuing a staggering number of arrest warrants — 9,000 in 2013 alone — often stemming from minor infractions, like traffic tickets. Fines mounted and jail stints lengthened for those who could not pay, resulting in an environment where both blackness and poverty were functionally criminalized.

In the time since, three young St. Louis-area residents whose activism — or proximity to activism — played key roles in bringing these issues to national attention have died. Darren Seals, 29, was found shot and incinerated in his car in 2016. Danye Jones, the 24-year-old son of activist Melissa McKinnies, was found dead in October, hanged by a bedsheet in his backyard in what authorities deemed a suicide. In November, 31-year-old Bassem Masri, who broadcast many of the protests to the wider public via his storied livestream, was found unresponsive on a bus and declared dead at a local hospital hours later. His cause of death remains undetermined. The number of young people who have died in the course of this sordid saga makes optimism a tall order, even with McCulloch — arguably its greatest villain after Wilson — finally out of a job.

But the fact that McCulloch is gone at all signals the possibility of voter-driven change. Organizers have spent years mobilizing residents to pay greater attention to prosecutor elections across the country. The result, in Ferguson, is the ouster of a man who refused to hold a killer accountable in favor of one whose official policies include no longer prosecuting marijuana cases where fewer than 100 grams are involved; not prosecuting people who fail to pay child support; and not requesting cash bail on misdemeanor cases, to name three. Whether Bell’s tenure meaningfully slows the momentum of the carceral apparatus that drives law enforcement in St. Louis County and beyond remains to be seen. But shifting a dynamic once defined by powerlessness to one rooted in influence suggests that accountability to black Missourians is not a pipe dream. Residue from Ferguson’s waking nightmare may still hang over the foreseeable future — the image of Brown’s dead body lying in a hot cul-de-sac for hours, ashes from the fire tearing down West Florissant Avenue, and the protesters dead too young remain indelible. But a St. Louis County prosecutor who is accountable to black voters more than arguably anyone who has held the office before is worth savoring. The arc of the moral universe may not organically bend toward justice, but sometimes, it can be bent.