Thomas Friedman is among the most successful political commentators in the world. A global readership devours his books on globalization. America’s premier newspaper prints his every reflection on current affairs. Event planners pay him more for a single speech than the median American household earns in a year. Awards committees shower him in prizes. Presidents seek his counsel.

And yet, there are still some Americans who can say that “we live in a meritocracy” with a straight face.

Forget Friedman’s past apologia for war crimes. Forget his praise of Russian autocracy, and the fresh prince of Riyadh (which is to say, forget “suck on this,” “keep rootin’ for Putin,” and “Arab Spring, Saudi style”). We need not cherry-pick from Friedman’s back catalogue to establish that he is living proof of a systematic market failure in the hot-take economy. An examination of his most recent column will suffice.

In “Is America Becoming a Four-Party State?” Friedman argues the following: The Democratic Party is growing ever more fractured between “grow-the-pie” moderates and “redivide the pie” progressives, while the GOP is on the cusp of a civil war between the “limited-government-grow-the-pie” right, and the “hoard-the-pie, pull-up-the-drawbridge” Trumpists. These unprecedented fractures in the two major parties — combined with the fact that globalization has rendered all traditional political divisions anachronistic — means that there is a significant chance that the U.S. will develop a four-party system by November 2020.

The problem with this argument is that none of its premises are true. In fact, some are so egregiously false, it is difficult to understand how anyone who reads the New York Times on a regular basis — let alone, writes for it — could actually believe them.

The Democratic Party is less ideologically divided than it’s been for most of its modern history.

Friedman writes that Democrats are suffering from a “deepening divide”; that the “level of outrage in its base” is “sky high”; and thus, while “our two parties have usually managed to handle deep fractures,” this “time may be different.”

For perspective: Throughout much of the 20th century, one wing of the Democratic Party believed that African-Americans deserved full civil rights and more economic aid, while another maintained that state governments had an inalienable right to look the other way when white people tortured and murdered uppity blacks. This disagreement — about whether the federal government had an obligation to assist the racially oppressed, or to “live and let lynch” — proved too insignificant to fracture the New Deal coalition during its first 16 years of existence. And even then, the Dixiecrat revolt failed to produce a durable third-party system. The structural barriers to such a development in American election law (among them, onerous requirements for ballot access, and a winner-takes-all election system that condemns third parties to spoiler status) proved too formidable. After Strom Thurmond and George Wallace threw their fleeting tantrums, southern Democrats gradually reconciled themselves to life beneath the GOP’s big tent.

The divisions in today’s Donkey Party don’t just pale in comparison to those of Harry Truman’s, but also of Bill Clinton’s, and (at least, arguably) Barack Obama’s. In the 1990s, Democratic voters and politicians disagreed about whether abortion services should be subsidized or banned; welfare, expanded or cut; immigration, increased or restricted; and Social Security, “reformed” or protected. Under Obama, this split over entitlement spending persisted. By contrast, in 2019, virtually all of the Democratic Party’s internal divisions aren’t about which direction policy must move on, but only how far. Last year, the party’s most conservative House candidates campaigned on their absolute opposition to cutting Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid, and in favor of incrementally expanding the state’s role in health care. Moderate Democrats want to expand tax credits for job training, while progressives favor free public college; but all agree that Uncle Sam needs to increase subsidies for labor-force development. Pro-life Democrats are, for all practical purposes, nonexistent. White Democrats have never been more “woke” on racial issues. In 2017, not a single congressional Democrat voted for Donald Trump’s tax cuts; in 2001, 12 Senate Democrats voted for George W. Bush’s.

It is true that, since 2016, an ascendant progressive wing has sought to move the boundaries of their party’s consensus leftward. But there is nothing remotely unusual about a major American political party being home to both incrementalist and radical wings. Moreover, as Sean McElwee of Data for Progress has demonstrated, the ideological divisions among the Democratic rank and file aren’t nearly as sharp as those among the party’s elected officials. In fact, Democratic primary voters have never been as ideologically united as they were in 2016; the vast majority of Bernie Sanders supporters have warm feelings for Joe Biden, and vice versa.

So, what is Tom Friedman’s evidence for the claim that the Democratic Party’s contemporary divides are more fatal than ever before?

Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’s office released FAQs about her Green New Deal resolution that suggested that the congresswoman supported guaranteeing economic security for people “unwilling to work.” Ocasio-Cortez’s office subsequently retracted that document, and one of her advisers explained that they never intended to endorse an unconditional, universal basic income. Rather, her chief of staff Saikat Chakrabarti explained that by those “unwilling to work,” they specifically meant late-career fossil-fuel-industry workers displaced by a Green New Deal.

“We were essentially thinking about pensions and retirement security,” Chakrabarti tweeted. “E.g. economic security for a coal miner who has given 40 years of their life to building the energy infra of this country, but who may not be willing to switch this late in his career.”

Nevertheless, one of the highest-paid, most-celebrated political analysts in the United States published a column — more than a week after Chakrabarti’s statement — arguing that Ocasio-Cortez’s (nonexistent) support for sloth subsidies reflects an intra-Democratic ideological divide so fundamental that it could break the American two-party system in a manner that trivial disagreements over the propriety of lynching never could.

Moderate Democrats do not care more about growth than progressives; they just care less about equality.

Here is how Friedman defines the Democrats’ intractable divide:

That phrase — economic security even for people “unwilling to work” — was not just noted by conservatives. It rattled some center-left Democrats as well, because it hinted that the party’s base had moved much farther to the left in recent years than they’d realized, and it highlighted the most important fault line in today’s Democratic Party — the line between what I’d call “redivide-the-pie Democrats” and “grow-the-pie Democrats.”

Grow-the-pie Democrats — think Mike Bloomberg — celebrate business, capitalism and start-ups that generate the tax base to create the resources for more infrastructure, schools, green spaces and safety nets, so more people have more opportunity and tools to capture a bigger slice of the pie.

Grow-the-pie Democrats know that good jobs don’t come from government or grow on trees — they come from risk-takers who start companies. They come from free markets regulated by and cushioned by smart government.

… Redivide-the-pie Democrats — think Bernie Sanders — argue that after four decades of stagnant middle-class wages — and bailouts for bankers and billionaires but not workers in 2008 — you can’t grow the pie without redividing it first. Inequality is too great now. There are too many people too far behind.

This is a cogent summary of how a self-proclaimed “grow-the-pie” (i.e., moderate) Democrat might understand the current divide within Team Blue. As such, it is tendentious and poorly substantiated.

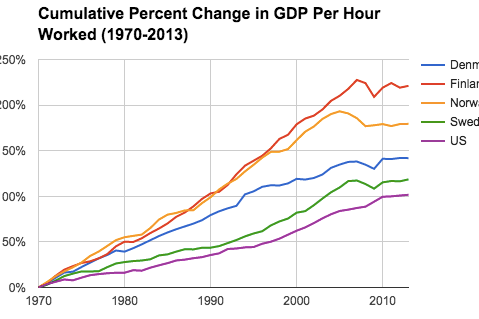

The government did not foster Friedman’s beloved “digital revolution” merely by regulating and cushioning “free markets.” It also directly funded and developed the technological advances that made the internet (and thus, Silicon Valley) possible. Risk-taking venture capitalists and entrepreneurs may create jobs by developing internationally competitive products, and discerning untapped consumer demands. But businesses can’t meet consumer demands when consumers do not have disposable income. And when the richest people in the country hoard income gains, and middle-class wages stagnate, mass consumer demand flags (and/or, becomes reliant on easy credit) — and so does economic growth. The explosion of inequality in the United States over the past four decades has not correlated with exceptionally high growth. In fact, the “redivide the pie” Scandinavian social democracies (which feature higher levels of taxation, redistribution, and state ownership than Bernie Sanders has dared to propose) have seen much higher growth in GDP per hour worked (a.k.a. productivity) since 1970 than the U.S. has.

Meanwhile, recent economic research has produced evidence that various forms of redistributive welfare spending increase aggregate productivity by improving impoverished children’s later life outcomes, that the key to stimulating innovation may be to increase workers’ wages and bargaining power (thereby forcing firms to invest in automation), and that inequality can indeed undermine economic growth by drying up consumer demand.

Moderate Democrats may emphasize their commitment to growth, while progressives put more rhetorical weight on the moral necessity of redistribution. But it does not follow from this that the former’s policy ideas are more conducive to growth than the latter’s. If an inevitable trade-off between reducing inequality and increasing GDP did not exist, there’s reason to suspect that American centrists would have to invent it. After all, if implementing Bernie Sanders’s agenda wouldn’t reduce growth, then it is awfully hard to rationalize opposing drastically higher levels of progressive taxation and transfers in a nation where the wealthiest 0.1 percent own as much as the bottom 90 percent, and the welfare state does not guarantee working people affordable health care or child care, in defiance of OECD norms.

To his credit, Friedman evinces support for incremental redistributive reforms. But the best-selling author does suggest that government and redistribution cannot “create good jobs” — and feels no obligation to substantiate his assertion with evidence of any kind.

Limited government is not the Republican Party’s “most core principle.”

After exaggerating and misconstruing the divides on the left side of the aisle, Friedman turns his foggy gaze to the right.

Trump’s decision to declare a “national emergency” on the Mexico border has violated the party’s most core principle of limited government. In doing so it’s opened a fissure between the old limited-government-grow-the-pie Republicans and the anti-immigrant hoard-the-pie, pull-up-the-drawbridge Trumpers.

There are a lot of problems with this dichotomy. Donald Trump’s decision to declare a national emergency, so as to divert a few billion dollars from one Executive branch account to another, is doubtlessly an affront to small government and the Constitution’s separation of powers. But surely, the last Republican president’s decision to let the NSA listen in on Americans’ conversations without securing a warrant and have the CIA operate an international network of torture black sites were even greater affronts to those concepts. And the same can be said of the Reagan administration’s direct contravention of Congress through the Iran-Contra affair. And yet, those violations of the GOP’s “most core principle” did not fracture the party; in fact, the architects of Iran-Contra enjoy prominent positions in the Republican Party to this day.

This might make you wonder whether a party that has spent the past half-century demanding endless expansions of the military-industrial complex — and of subsidies for its favorite corporations — might not value “limited government” so much as upward redistribution.

If so, you are not Tom Friedman. In fact, Friedman proves himself impervious to evidence that contradicts his thesis even when he himself provides that evidence. Immediately after claiming that Trump’s emergency declaration has opened a fissure that just might break the GOP in half, Friedman writes:

The early signs are that the limited-government types — led by Mitch McConnell — are so morally bankrupt, after having sold their souls to Trump for two years, they’ll even abandon this last core principle and go along with Trump’s usurpation of Congress’s power of appropriation.

The Pulitzer Prize winner then carries on with his argument, as though he has not just explained why it isn’t true.

All of the traditional conflicts in American political life have not become archaic and irrelevant.

Not content to ahistorically declare intractable crises within both major political parties, Friedman concludes by ahistorically announcing the death of all the conventional political divides in Western democracies:

Ever since World War II until the early 21st century, the major political parties in the West were all built on a set of stable binary choices: capital versus labor; big government/high regulation versus small government/low regulation; open to trade and immigration versus more closed to trade and immigration; embracing of new social norms, like gay rights or abortion, and opposed to them; and green versus growth.

Across the industrial world parties mostly formed along one set of those binary choices or the other. But that is no longer possible.

What if I am a steelworker in Pittsburgh and in the union, but on weekends I drive for Uber and rent out my kid’s spare bedroom on Airbnb — and shop at Walmart for the cheapest Chinese imports, and what I can’t find there I buy on Amazon through a chatbot that replaced a human? Monday to Friday I’m with labor. Saturday and Sunday I’m with capital. My point? Many of the old binary choices simply do not line up with the challenges to workers, communities and companies in this age of accelerating globalization, technology and climate change[.]

These ravings are so detached from empirical facts or logical coherence that they would seem self-refuting if printed in a comments section or shouted from a street corner. But since they were penned by one of America’s preeminent columnists, in the nation’s paper of record, let’s review why the advent of Uber drivers did not condemn all conflicts between capital and labor to the dustbin of history.

The existence of unionized workers — who also consume imported goods, and therefore, benefit indirectly from exploitative labor practices in the third world — is not a new development. Nor, for that matter, is it especially novel for a working-class family to supplement their income by renting out a spare room. (Also, the kid has his own spare room? Or did the steelworker convert his kid’s room into a spare room? If the latter, where is the kid sleeping? Is the steelworker a capitalist now because he sold his own dang kid?)

Uber is a relatively new company. But Uber drivers have no particular reason to identify with capital instead of labor; the average Uber driver makes about $10 an hour, and lacks many of the basic benefits that unionized workers take for granted.

Furthermore, it is hard to imagine why an American who performs hard labor five days a week, works as a cab driver on weekends, tends to Airbnb tenants in the evening — and still can’t afford anything but “the cheapest Chinese imports” at Walmart — would find the notion of a fundamental conflict between capitalists and workers alien to his experience.

Beyond the psychedelic incoherence of Friedman’s conception of the contemporary precariat, there’s a more basic problem with his analysis: Virtually all of the “binary choices” that he rattles off do, in fact, cleanly divide America’s two major parties in 2019. The Trump-era GOP has tried to cut programs that benefit labor, so as to finance tax cuts for capitalists. Democrats have opposed those measures, and put forward a variety of plans for redistributing resources in the opposite direction. Republicans are trying to restrict gay rights and access to abortion on both the state and federal levels; Democrats are working to do the opposite. Immigration now splits the two parties more sharply than at any time in our modern history.

If you are a gay Mexican-American with undocumented family members, who relies on Medicaid for affordable insulin, in what sense do the “old binary choices” not line up with the challenges you face? What if you are the median American family whose wages have not kept up with the rising costs of health care, housing, and higher education?

The esteemed columnist does not say.

Instead, he is content to toss a mess of thinly connected ideological assertions beneath an absurdly hyperbolic question headline that he barely bothers to defend.

And since the free market in hot takes rewards such tripe — and capitalism compels us all to subordinate our values to the profit motive — lesser columnists are often forced to do the same.