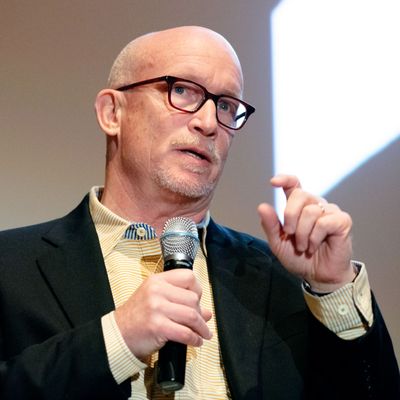

I spoke last Thursday with Alex Gibney, director of The Inventor: Out for Blood in Silicon Valley, HBO’s new documentary about Theranos and Elizabeth Holmes.

The film follows Holmes’s path from dropping out of Stanford in 2004 to found Theranos, a company built on the bold promise of building small, in-home machines that could perform hundreds of blood tests on tiny, pinprick drops of blood; through her becoming the first female billionaire company founder in Silicon Valley and a global business celebrity; onward to Wall Street Journal reporter John Carreyrou’s disclosure in 2015 that Theranos’s technology did not work as promised, and the company’s subsequent implosion.

Along the way, Theranos deployed ineffective blood-testing technology through testing centers at dozens of Walgreens stores, providing unreliable results that endangered patients’ health. And it raised (and spent most of) $900 million from investors, whom it misled about the effectiveness of its technology.

My interview with Gibney has been condensed and edited for clarity.

Intelligencer: How did you get the rights to all that internal Theranos footage: meetings, marketing materials, and that sort of thing?

Gibney: I didn’t. [Laughs.]

Intelligencer: So, it’s fair use?

Gibney: Fair use, yes.

Intelligencer: How did you even obtain it?

Gibney: It was leaked to me. Some of the material is licensed, because she appeared at gatherings. Like, the very beginning of the film, her against the white scrim: That’s an appearance she made at Condé Nast; it was a series of questions they asked a lot of executives.

But a lot of the material showing company meetings, some of the direct-to-camera interviews with Elizabeth: That was material that was shot by Theranos as a way of chronicling its early genius. I think Elizabeth had this notion that it was going to be like having a camera with Woz and Steve Jobs in the garage.

Intelligencer: I want to ask about the visualization of the disgusting interior of Theranos’s Edison blood-testing machine. Was there a plan about how that would be maintained? Was the expectation that the consumer would have to clean that out by hand?

[As Emily Yoshida wrote for Vulture, after seeing the film at the Sundance Film Festival, “One of the most memorable images in any documentary this year will surely be that of a CGI recreation showing the disastrous insides of an Edison box, splattered with blood samples, broken pipettes, and roving, infected robotic needles, lying in wait for anyone who would dare stick their hand inside to fix something.”]

Gibney: That’s a good question. I think that the expectation was that there wouldn’t be a lot of breakage, that there wouldn’t be a lot of spillage. And obviously, at least initially, the plan was to put the machines in Walgreens, not into homes. Over time, the hope was that you could get them into homes. But yeah, that was a way of illustrating how far it was from reality.

Intelligencer: There’s a narrative you sometimes hear about Theranos, and I think it can be read into your film, that Elizabeth Holmes was somebody who got carried away. That she had this big vision, and she thought she was faking it ’til she made it, and she didn’t really understand that she didn’t have a product. Is that your take on it, that she really, genuinely thought the whole way through that she was doing a wonderful thing for the world?

Gibney: There was certain amount of — a lot of cognitive dissonance going on. I think she knew that the machine had problems. But there was a kind of willful denial. I don’t see that as the good news. I see that as the bad news.

That’s very much the way Jeff Skilling thought of Enron. Even though they were loaded up with debt, with all these special-purpose vehicles, he had this grand vision of the company that he was unwilling to let go. And so he refused to admit to himself psychologically, except late at night, that they had edged way over into the terrain of fraud.

You might think that the same thing happened with Elizabeth. She got desperate at a moment when they were running out of money and Walgreens was about to pull out. And they desperately needed Walgreens [even though they didn’t have a blood-testing machine that was ready to be deployed to Walgreens stores].

So they came up with these kinds of screwy workarounds to keep Walgreens in. One was to do straight venous draws, which would then be analyzed with regular commercial machines. The other was to jury-rig the commercial machines to work with small quantities of blood.

And that’s where I think Elizabeth’s willful denial, you can’t be so generous about that. You have to be hugely critical, because she was putting patients’ lives at risk.

Intelligencer: That’s where they went from just defrauding investors to also defrauding the consumers.

Gibney: Correct. And frankly, you have a machine that isn’t working, and you have investors investing in research and development, you could properly say to them, “Look, it’s just not working, but we’ll get there.” And investors can either decide to keep in, or not. But it is clear that they were doing demonstrations that were, you know, sometimes deceptive and sometimes outright fraudulent.

Intelligencer: That was what struck me when I read John Carreyrou’s Bad Blood: The anecdote all the way back in 2006, with her making a fraudulent representation to investors, and the CFO telling her she couldn’t do that, and her firing him for that. There was the shift — they started misleading consumers much later in the company’s life — but that’s what makes me feel like, from the beginning, she was just lying her ass off to everyone in a way that was not normal Silicon Valley puffery.

Gibney: You’re quite right to point out that part in John’s book, and it’s very damning. But I do think she had her eyes on a noble mission.

Elizabeth may have started cheating in 2006, but I think that is consistent with the “noble cause corruption” that [behavioral economist] Dan Ariely describes in his dice experiment. In the service of a good cause, people sometimes cheat more, and more effectively, because they don’t feel they are doing anything wrong. The end justifies the means.

For example, when Lance Armstrong would proclaim, in essence, “how dare you say that I, as a cancer survivor, would ever use performance-enhancing drugs,” he might believe it in the moment he said it, even though he might do [blood doping] the same day. What allows him that purposeful self-deception is belief that he was telling a lie that cancer patients — for whom he was raising millions of dollars — needed and wanted to hear.

In the case of Elizabeth Holmes, this noble cause corruption is not an excuse for bad behavior. It’s a diagnosis of a psychological mechanism that is designed to deceive both the person telling the lies and the people hearing them. The best liars are the ones who are convinced they are doing it for a good cause. Sometimes, they may even come to believe that they aren’t lying at all.

I don’t think she was like Bernie Madoff where, you know, he decided he couldn’t make it, and so now he was going to run an outright scam. You’ll recall that when they come and take Madoff away, he’s sort of like — it’s almost like, “I’ve been waiting for you. I’m a crook.” You know, “Come take me.”

Intelligencer: Right.

Gibney: When Elizabeth is outed by the Wall Street Journal, she doesn’t say, “You got me.” She doubles down in a way that’s almost messianic. And I think that testifies to this notion that she did have this vision of the goal she wanted to get to.

But she was also young, and she was reckless, and she was apparently willing to cut corners from the beginning.

I think it’s easy to imagine her — and I think a lot of Silicon Valley likes to do this — as somebody who’s just a complete outlier, doesn’t have anything to do with Silicon Valley. I just don’t think that’s true. I think she’s an exaggeration of some flaws.

Intelligencer: Did you find a lot of people expressing embarrassment about having been taken in? I mean, obviously, you got that from some of the journalists, but did you speak with investors or employees who really were sort of like, “How the hell did I fall for this?”

Gibney: Well, I think they all did. Even [whistle-blower employees Tyler Schultz and Erika Cheung] would say that they fell for it at least initially. And then it took a while, even though they were seeing it up close and personal in the lab.

And of course, Walgreens wouldn’t even talk to me because they’re clearly so embarrassed about what happened. Even in the documents of the initial [Walgreens–Theranos] lawsuit, before they settled, you can see how angry they were, and yet, they were clearly complicit in it. They were blinded to the facts of the matter by their exhilaration about doing something in tech, which I think they felt they needed to do, and they were completely steamrolled by the force of Elizabeth’s storytelling skills. So much so that they didn’t even look inside the fucking box.

But so like, [venture capital investor] Tim Draper is unapologetic to this day.

Intelligencer: Why do you think that is? On some level it’s the job of both the journalists and the investors to get these things right, for different reasons.

Gibney: I think there’s a line of narration in the film, “We like to think that investing is a balance of risk and reward” — you know, carefully calculated. But I think it has a lot more to do with emotion and subjectivity than we would like to think. And same thing with journalism.

You like to believe that you’re the rigorous, distant scientist, but there was a very compelling story. It was a story not only about a device that would allow people to take more control of their own health care. It was also a story about a young, female entrepreneur who could stick it to the male-dominated world of Silicon Valley and make a success.

That’s part of what I was trying to get at in the film, even going back to Thomas Edison, the first guy who kind of made himself into a kind of celebrity businessman. There were a lot of things that Edison didn’t do that he took credit for. But everybody was willing to invest in that idea because he created this mythic sense of the magical inventor, the Wizard of Menlo Park. And people liked that story. It was a story they wanted to tell. I think these things are powerful, more powerful than we think.

Intelligencer: But Thomas Edison also had products.

Gibney: He did have products, ultimately. But the incandescent light bulb didn’t work when he said it did. And he was faking tests.

There’s a wide difference between Elizabeth and Steve Jobs and Elizabeth and Thomas Edison, because her products didn’t work. But I’m also saying, if you think about the huge number of inventions that Edison effectively took credit for, you know, he wasn’t the inventor, he was the storyteller. And same thing with Jobs. That’s what I think Elizabeth shares in common.