Shortly after news broke this month that Bill Shine would resign as the White House communications director and deputy chief of staff, a person knowledgeable about his decision told me the former Fox News exec had come to understand the counterintuitive dynamic that defines many of Donald Trump’s relationships: Proximity can be meaningless, as those who have his ear are often out of his sight. “When you talk to him at night, you’re gonna have more impact than sitting in a room with six people,” the person said, referencing the president’s after-dark practice of calling and fielding calls from a vast network of informal advisers.

Trump abides by what I call the “Groucho Marx Law of Fraternization,” meaning anyone choosing to be near him is suspect while everyone else gets points simply for existing elsewhere. “He always kind of wants what he doesn’t completely have,” the New York Times’ Maggie Haberman once said. “You are never more valuable to Donald Trump than when you’re walking away from him.”

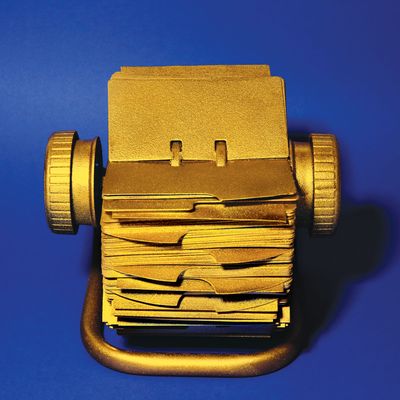

What explains this social idiosyncrasy? Obvious answers, like self-loathing, don’t quite feel complete. But whatever the psychological cause, the effect is manifest in at least one thing: his compulsive phone habits. His Rolodex is a Greatest Hits and Deep Cuts composed of mostly friends, associates, media figures, and tycoons. Although Trump is known to call senior members of his staff at all hours, his informal advisers share a common attribute: They’re not there and, therefore, they can’t be blamed when things are falling apart. Their praise sounds less sycophantic and, therefore, more compelling; the president seems to grant the calls coming from outside the White House an inherent credibility. They are also a welcome distraction, a link to his old life in Trump Tower, when concepts such as “executive time,” a term used by aides to make it seem like the president is doing something productive when he’s fucking around and calling TV-show hosts to gossip about ratings (a subject of intense interest for him, even now), were irrelevant.

Over the last two years, current and former officials from his campaign and White House, as well as his friends and acquaintances, have provided information about Trump’s Rolodex to New York. One source almost literally provided a Rolodex, sharing an internal document from the Trump Organization with contact information for 145 employees and 26 individual departments within Trump Tower. In the White House, a similar document exists: The switchboard operators maintain a list of cleared callers, a few dozen outsiders, whose contact with the president was sanctioned by Trump’s second chief of staff, John Kelly. The list includes Eric Trump, Don Jr., Sean Hannity, Stephen Schwarzman, Rupert Murdoch, Tom Barrack, and Robert Kraft.

And then there are the unsanctioned callers. The outgoing contact from the Oval Office or the residence is unregulated, learned of only after the fact from the call logs kept by switchboard operators, while the calls to and from Trump’s cell phone are unknown — a mystery to the official staffers who long ago abandoned any hope of controlling who the president speaks to when they’re not around. And mostly they’re not around. Those who can’t call the president directly often went through Hope Hicks, Trump’s trusted communications director, until she resigned last year. Often, information has come through Rhona Graff, the longtime gatekeeper of Trump Tower who has served as a channel for those seeking to quickly get a message to the president outside the official communications structures. As Roger Stone told the journalist Tara Palmeri in 2017, Graff was the route for “anyone who thinks the system in Washington will block their access.” Others to endorse this plan? Gristedes’s John Catsimatidis.

Last month, Trump’s former personal attorney Michael Cohen testified before Congress and confirmed that “Mr. Trump” doesn’t email or text. In 2014, the journalist McKay Coppins wrote that Trump still used a flip phone “because he likes how the shape places the speaker closer to his mouth.” But by the time he was running for president, he possessed both an Android and an iPhone, from which he lobbed countless tweets and international news cycles. In Team of Vipers, Cliff Sims, a staffer on Trump’s campaign and in his West Wing, described how, on Election Night 2016, as everyone else anxiously watched the returns, Trump was “casually” accepting calls from blocked numbers and, at one point, yelled out for someone to “get Rupert on the phone” (Murdoch later called to congratulate Trump, who told him, “Not yet, Rupy,” according to Sims). The first time I walked through the West Wing, a few weeks after Inauguration Day, I was confronted by a large photo of Trump talking on his unsecure Android hanging in a stairwell. He continued using unsecure personal devices, allowing Russia and China to spy on his calls, according to the New York Times (in response to the report, Trump tweeted, “I only use Government Phones, and have only one seldom used government cell phone. Story is soooo wrong!”)

Most profiles of Trump since the 1980s have featured a description of him making a phone call or a phone conversation between the writer and the chatty subject. Marie Brenner, in her seminal portrait of Trump’s Chumbawamba era, “After the Gold Rush,” said one such conversation went on for two hours. My first interview with Trump, in 2014, was by phone, which isn’t in itself unusual; lots of interviews happen that way. What was unusual was how much of Trump came through the receiver, a level of comfort that suggested he was picking up a conversation with someone he’d known for years rather than not at all. Normally, distance can create a barrier, but with Trump, it’s almost like, by removing the distraction of his physical being, he can become something approaching human. I wrote then that his voice conveyed a surprising sadness.

In February, Axios obtained three months of Trump’s unofficial daily schedules, revealing that for a staggering average of 60 percent of each workday, or the period between 8 a.m. and 5 p.m., the president engaged in “executive time.” But what happens after 5 p.m.? The president usually leaves the Oval Office around seven. His dinners rarely take place “off campus,” meaning off the White House grounds. By eight, he’s watching Fox News in the residence, and by the time Hannity ends, at ten, he’s on the phone, often with Hannity himself, or with one of the other members of his external cabinet, or just anybody else he feels like talking to. Politicians in Washington — and their family members — have spoken about receiving calls from the president with almost alarming frequency. So many calls that they interrupt wood-chopping or interactions with constituents or, in the case of one call between Trump and Mitch McConnell, a Nationals baseball game. Trump will call if he sees you on TV and likes something you said. Or if he sees you on TV and hates something you said. He’ll also call to try to change your mind or to try to get you to change someone else’s mind. Or just to chitchat about golf. “I just feel comfort in calling President Trump,” Senator John Barrasso said to the Washington Post. Lindsey Graham told Mark Leibovich this is the most contact he’s had with any president. And Graham is still answering the calls, even though, during an antagonistic period, the president once read Graham’s private cell number aloud onstage at a rally, forcing Graham to change his number.

Former staffers, whom Trump rarely banishes completely from the outermost sphere of his orbit, have told New York about receiving unexpected evening calls from their old boss. One former campaign official said that, after not hearing from him for months, the president rang to ask if it was a good idea to send a certain tweet. The ex-official said he had the impression everyone else had told Trump no and he was searching for someone who might tell him yes.

One person who has received late-night calls from the president told me this: “If you’re Trump, the last thing you want is a moment of self-reflection. That’s why he’s constantly on the phone at night. Everybody’s afraid of themselves. People fear silence because they don’t want to hear voices. But Trump really fears that.”

*This article appears in the March 18, 2019, issue of New York Magazine. Subscribe Now!