Stephon Clark was shot and killed on March 18 in his grandmother’s backyard in Sacramento by two police officers who claimed they thought his white cell phone was a handgun. As with Michael Brown and Freddie Gray before him, his name became shorthand for a nationwide pattern of police violence against black men. That his killers would not face trial was the probable outcome well before Xavier Becerra made it official.

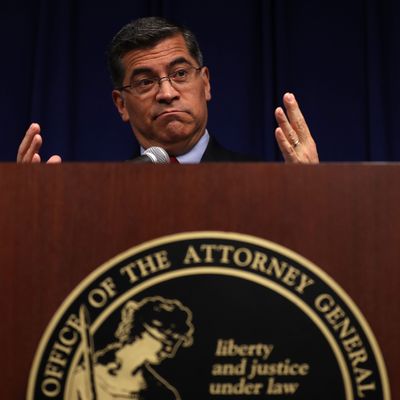

Speaking on Tuesday to reporters in Sacramento, the California attorney general cited a ten-page report summarizing an almost yearlong investigation by the state’s Department of Justice into the incident. “Our investigation has concluded that no criminal charges against the officers involved in the shooting can be sustained,” Becerra said, echoing a similar conclusion announced on Saturday by Anne Marie Schubert, the Sacramento County district attorney. “I know this is not how Clark’s family wanted this story to end.”

Surely not, but the decision was far from unexpected: Just 80 American police officers were charged with murder or manslaughter for on-duty shootings between 2005 and 2017. This despite the staggering number of civilian deaths by firearm for which they are responsible — hovering between 900 and 1,000 during each of the past three years, according to a running Washington Post tally. Of the 80 charged, just 35 percent have been convicted, a figure that attests to the difficulty of securing criminal convictions for men and women who are granted de facto impunity to take lives.

Becerra is certainly aware of this track record. And by refusing to let a jury decide the officers’ fate, he has joined a robust legacy of prosecutors unwilling to take firm stances against the police. This approach was desirable among his fellow Democrats for much of the late-20th and early-21st centuries. The party was fixated then on burnishing its “tough on crime” bona fides as an electoral strategy against Republicans and, sometimes, in response to actual crime spikes. But today, it has arguably become a liability — both for criminal-justice reform broadly, and for Becerra’s credibility more specifically. At a time when advocates and officials in his home state are fighting to reshape California’s criminal-justice system by eliminating cash bail and rebuking President Trump’s anti-immigrant crackdowns, Becerra’s decision belongs squarely among the mistakes of his predecessors.

Clark, 22 when he died, had allegedly spent the minutes before his flight from police smashing a car window and throwing a cinder block through a neighbor’s sliding glass door. He was mentally unwell — a fact affirmed by an internet-search history rife with inquiries about how to commit suicide, and a series of subsequent suicidal threats he’d made to his girlfriend in the days prior. He had allegedly assaulted the same woman two days beforehand as well, which had nothing to do with the circumstances around his death but was nevertheless a point of emphasis in Schubert’s rationale for declining to charge his killers.

Clark was shot eight times that night, with an independent autopsy concluding that almost all of the bullets had entered his back. Becerra and Schubert’s offices both pursued independent investigations of the shooting, in Becerra’s case at the request of local police. Nearly a year later, their conclusions suggest that, despite several years marked by anti-police brutality protests, some prosecutors continue to err on the side of protecting their relationships with police, and police unions, rather than pursue accountability for law enforcement within a system stacked against it.

Becerra — despite his background as a pro-workers’ rights progressive during his time in Congress — is in some ways an exemplar. In February, his office threatened legal action against a group of Berkeley, California–based journalists who had received a list from state commissioners, apparently by mistake, of California law enforcement officers who had been convicted of crimes. Becerra received more than $300,000 from police unions statewide during his last campaign — suggesting a coziness with law enforcement that might explain his opposition to greater accountability and transparency for them, despite what the Berkeley reporters said is the public’s right to know. But this approach may be nearing its last hurrah.

Central to the current pushback against law enforcement overreach from progressives and the Democratic Party’s left wing is a growing awareness that prosecutors are key drivers of inequality. At the local level in particular, they both over-prosecute their poor and often black or brown constituents and regularly decline to take police to task for misconduct and brutality. The latter perception has led to protests — most famously, those affiliated with the Black Lives Matter movement — and the ouster by voters of top cops in several jurisdictions, like Anita Alvarez in Cook County, Illinois; Timothy McGinty in Cuyahoga County, Ohio; and Robert McCulloch in St. Louis County, Missouri, to cite three.

The ramifications of this approach to crime policy have already been felt at the national level. Senators Kamala Harris and Amy Klobuchar and former Vice-President Joe Biden are on the wrong end of the sea change in their party’s approach to criminal justice. All three of their burgeoning or prospective campaigns for the presidency in 2020 are waging an optics war against their records as punitive, police-friendly prosecutors (or, in Biden’s case, as a United States senator) — records marked by what many view today as an excessively harsh approach to crime.

Harris and Biden have addressed this shift by expressing varying degrees of regret for their past conduct, while also maintaining, in so many words, that their behavior was a product of its time. “We were told by the experts that ‘crack, you never go back,’ that the two were somehow fundamentally different,” Biden said at a Martin Luther King Jr. Day breakfast hosted by Al Sharpton, attempting to absolve himself of the “mistake” he made in the 1980s by supporting laws that criminalized crack more harshly than powder cocaine. For her part, Harris has attempted to recast herself as one of the original “progressive” prosecutors — a claim partly supported by her implementation of diversion programs for first-time offenders and anti-bias trainings for her staff, but undercut by some truly horrific pursuits, like prosecuting the parents of truant schoolchildren during an era of falling crime rates. (Klobuchar, who is currently facing allegations that she terrorizes her young staff by humiliating them publicly and throwing objects at them, has made no such concessions.)

Yet even if one finds these arguments convincing — and I am inclined not to — Becerra has no such excuse. He is fortunate, as all of us are, to exist at a time when it is clearer than ever that unaccountable law enforcement paired with a punitive approach to crime and mental health crises in black communities does significantly more harm than good. He is no helpless victim of his era, as his predecessors have claimed to be. Americans have decades of misled policy to look back upon and use as a bellwether for today. To the extent that history can be used as a guide, the lessons regarding how to earn public trust is clear. Instead, Becerra has embraced the old way. It is to his detriment, and to California’s.