Editor’s note, May 16, 2019: I.M. Pei died last night at the age of 102. This story, published on April 17, 2017 and republished today, celebrated him on his centennial.

In the early 2000s, when I. M. Pei was well into his 80s, he went on a tour of the Middle East to bone up on Islamic architecture before designing one of its major monuments. His mission was to erect a museum that did not yet exist in a city that had recently been built from scratch. He selected a site on an island that had to be made and paid homage to a tradition he didn’t know and a religion with which he had no prior relationship. Somehow all that foreignness produced a late-period masterpiece, the Museum of Islamic Art in Doha, Qatar.

Over the course of his career, the aristocrat of American architects, who turns 100 on April 26, has drawn on a dazzling range of influences, from Chinese gardens to ancient Colorado cliff dwellings to the fountain in a Cairo mosque. He blended the austere modernism of the Bauhaus with opulent Beaux-Arts classicism, technological daredevilry with reverence for precedent and a minute study of the past. The best of his creations, like the East Wing of the National Gallery in Washington, D.C., look at once audacious and inevitable. He designed a skyscraper for the Bank of China whose exuberant asymmetry snapped the Hong Kong skyline into focus. Even designs that were never built (an astonishing corkscrew tower intended to rise above the FDR Drive near the Queensboro Bridge) or that wound up bowdlerized (the JFK Presidential Library in Boston) failed with panache.

Born a banker’s son in Shanghai, Pei arrived at MIT in 1935 as an engineering student and later attended the Harvard Graduate School of Design. By the time he was done with his studies, the Japanese had gone to war with China and bombed Pearl Harbor. He was not going home anytime soon — not, as it turned out, until 1974. Armored with a light but distinct accent and an air of gentlemanly reserve that would have behooved an English prince, Pei felt at ease around power. He knew how to talk to Jackie Kennedy, Paul Mellon, François Mitterrand, and, early in his career, the hurricanelike New York developer William Zeckendorf.

Pei was working as Zeckendorf’s in-house architect in the ’50s, when he designed the affordable-housing complex at Kips Bay Plaza. The immense grids of precast concrete can feel gloomy and even anti-urban in their brooding, repetitive length, but at the time, their muscular minimalism seemed boldly idiosyncratic, a world away from the generic brick boxes of public housing. The project was a triumph of stinginess and practicality, the kind of accomplishment that might have led to a life of frictionless corporate servitude. Even long after he had formed his own firm and been anointed a past master, he still fretted that he might have sacrificed artistry to ingenuity. In 1979, the Times critic Paul Goldberger found him in a reflective mood: “Maybe my early training set me back. Maybe it made me too much of a pragmatist,” he said. He was 62, with three decades and several more masterworks left to round out his career.

Pei’s cultivation and taste, and his belief in the redemptive power of architecture, could lead him fantastically astray. At Zeckendorf’s behest, he designed a stylish skyscraper, shaped like an elongated hourglass, to replace Grand Central Terminal, which he dismissed as “second-rate.” He would have brought “order” to the architectural “chaos” of Columbia’s Morningside Heights campus by flanking the south lawn with a pair of ungainly towers. In a rare fit of architectural wisdom, Columbia scotched the plan.

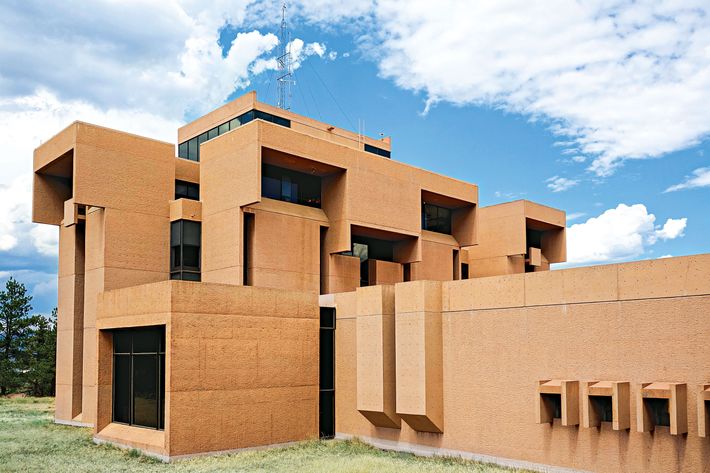

More often, though, he discovered unsuspected solutions lying out in the open. In the early ’60s, when space seemed navigable and the skies knowable, he was asked to design the National Center for Atmospheric Research on the edge of Boulder, Colorado, and was almost flummoxed by the glories of the mountain site. Eventually, he visited the Anasazi village carved into the earth at Mesa Verde National Park and came away determined to fashion something similarly powerful, perpetual, and enigmatic. He produced a cluster of reddish concrete columns, as heavy and pensive as a stand of spruces or Rodin’s Burghers of Calais. With thick walls, sparse windows, and narrow balconies hooded by slablike roofs, the complex’s stony beauty suggests both the mysteries of science and the ruggedness necessary to study the pitiless weather.

Given Pei’s penchant for elegant solidity, it’s ironic that the project that nearly sank the firm was the Hancock Tower in Boston, a glass edifice so ethereal that clouds seem to glide right through it. Construction of the tower damaged nearby Trinity Church. Then the curtain wall began to crack, and for a while workers patched the broken windows with plywood panels, making the façade look diseased. Finally, an engineer discovered that a strong wind might knock the structure over, and it had to be reinforced with 1,650 extra tons of steel. Pei’s partner Henry Cobb had designed the building, and the tower opened in 1976 to become a Boston landmark, but notoriety clung to the firm.

Pei managed to wash away the Hancock taint, partly with the East Wing of the National Gallery, which opened in 1978. A pair of nested triangular forms taper to an edge so sharp that visitors get a frisson from stroking it, using it as a gun sight for photos of the distant Capitol. The white H-shaped façade invites visitors into an atrium that balances clarity and complexity, sliced by bridges, hung with a giant Calder mobile, and topped by a spectacularly luminous glass roof. (The East Wing recently reopened after a sensitive renovation.) In the decade-long process from contract to completion, Pei demonstrated his virtuosity with every tool of his profession, navigating tortuous politics, protecting the design’s integrity, and developing a contemporary architectural language that merged formality with warmth.

He also indulged his penchant for geometric precision, a love that bloomed in his renovation of the Louvre Museum. When France’s President Mitterrand tapped Pei for the project, the architect faced attacks that ranged from stylistic criticism to outright racism: How could a not-French, not-European — not even fully Western! — quasi-modernist dare to tamper with a great (if neglected) icon of national culture? Pei responded with a design that invoked the geometric purity of the 18th-century French architect Étienne-Louis Boullée and also gave Paris a jolt of modernity as bracing as the Eiffel Tower.

He carved out a new underground entrance in the central court of the U-shaped building, then topped it with a crystal pyramid and a set of triangular pools. The crisp planes embraced by arms of ornate stone, the skin of water reflecting Paris’s turbulent skies, the transparent portal to an underground realm, the stagy staircase that spirals down into the atrium like a long curl of orange peel — all these features now seem so intuitively correct that it’s easy to forget how many experts howled about each one. With the simplest of gestures — albeit one hugely complicated to execute — Pei had transformed a great creaky mess of a museum into a modern palace of blockbuster shows, able to handle multitudes.

He has been called the wrong man for many different jobs. The architect and critic Michael Sorkin recounts calling Pei in 1987 and half-jokingly demanding that he turn over the task of designing the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in Cleveland. “What do you know about rock and roll, I. M.?” Sorkin asked. The elder architect politely answered that he knew all about popular music thanks to his son: “T’ing gave me a book!” he explained. That cultivated naïveté has served him well. When the call came from Doha, he responded with the confidence and humility to revisit his education and forge a new style, yet again, in his 80s. A signature, he once said, is a trap. “I don’t envy the architects who have such a strong stylistic stamp that clients would be disappointed if they do not get the same ‘look’ in their projects … I think I have greater freedom.”

He trained that freedom on the Museum of Islamic Art, a bleached mirage like a palace of sugar cubes emerging from the Persian Gulf waters into the hard glare of Doha. Like Candide searching for happiness, Pei went hunting for the “essence” of Islamic architecture. He rejected the Great Mosque at Córdoba, the Umayyad Mosque in Damascus, and the Ribat fortress in Tunisia and finally found what he was looking for in the pared-down tranquillity of the Mosque of Ahmad Ibn Tulun in Cairo. There, a round dome on a square chamber in a large arcaded court expressed the nested geometries that had danced through his mind for decades. In the museum he finally designed, the purest distillation of Islamic architecture turns out also to yield the perfect synthesis of the Beaux-Arts polygons and stern modernist orthodoxies he had absorbed as a student in the 1940s; of all the solid, rocklike presences and airy atria he had conjured; of all the deluxe surfaces and liquid light he had ever choreographed. On his way to his centennial, I. M. Pei struck out on a quest through exotic lands and finally found himself.

*This article appears in the April 17, 2017, issue of New York Magazine.