This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

The scandal started with a party, of course, because this was Palm Beach. It took place last year, during the winter season, when the rich men arrive on their jets with their third wives and the island swirls with charity benefits and gossip. A few opulent venues compete to hold society events, including Mar-a-Lago, the estate Donald Trump runs as a private club. But since 2016, many charities have shunned the president’s impolite company, opening the way for a new social set. In February 2018, a Jewish activist known for walking around Trump-campaign rallies in a Stars and Stripes–patterned blazer staged a big affair at Mar-a-Lago, which he promoted as an act of patriotic and financial solidarity with the president.

It was called the Truth About Israel Gala. Tickets started at $750. A VIP package, priced at $3,000, included dinner for two, “meet and greet privileges,” and “autographs.” Diamond and Silk, the pro-Trump social-media personalities, provided the entertainment. A “speed painter” was on hand to produce portraits of Donald and Melania for sale at an auction. A well-known local rabbi, Leonid Feldman, was invited to give the invocation.

When the rabbi arrived, he encountered a strange scene. “As I come out of my car, I see a bunch of Chinese people dressed to kill,” Feldman said. “I turned to the couple next to me and asked, ‘Is this the right event?’” Inside the club, dozens of other Asian guests were jostling around the pool, snapping selfies with the president’s Spanish-style stucco mansion in the background. Many of the visitors spoke little English, but they were eager to network. They posed for photos with Ron DeSantis, now the governor of Florida. One man brandished marketing materials for a Chinese electric-toothbrush company.

“I collected probably 25 business cards — president of this, CEO of that,” Feldman said. “I was told the Chinese people are fascinated by Mar-a-Lago, and maybe also they thought they were going to meet the president.

The whole thing was bizarre.”

At the center of the confusion, wearing a royal-blue gown and carrying an embroidered MAGA clutch, was a ChineseAmerican businesswoman named Cindy Yang. She had materialized that season in Palm Beach. First she started coming to Mar-a-Lago, then she started bringing friends. Sometimes Yang would buy party tickets in bulk, providing a welcome subsidy to organizers — and, indirectly, the president of the United States. Mar-a-Lago’s revenues dropped by 10 percent last year, financial disclosures show, but the decline would have been even more dramatic had it not been for a phenomenon that Palm Beachers describe as “Trump tourism.” The socialites might turn up their noses, but there are plenty of other wealthy individuals, many of them foreign, who are more than happy to pay for access to Trump’s orbit. Providing that access was Yang’s business.

Even as relations between Trump and China were taking a hostile turn over trade and other issues, Yang was acting as a for-profit goodwill ambassador. On the Chinese-language website for her company GY US Investments, she promised she could open the gates to Mar-a-Lago and the president. The Israel gala met with mixed reviews in Palm Beach — Shannon Donnelly, the veteran society columnist for the Palm Beach Daily News, pronounced the party “weird” — but Yang’s site portrayed it as a crowning achievement to people back in China, displaying a gallery of party shots.

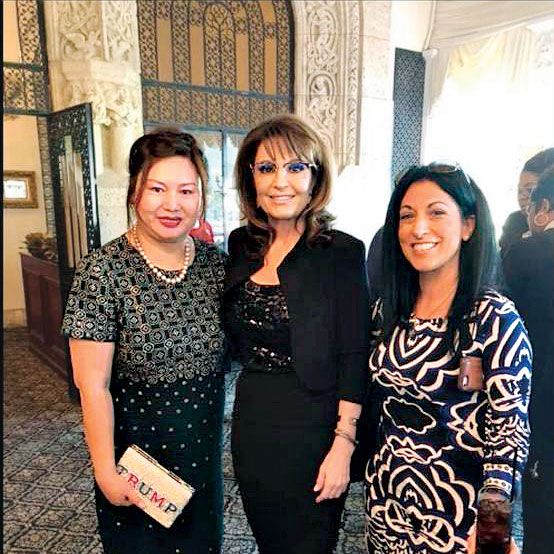

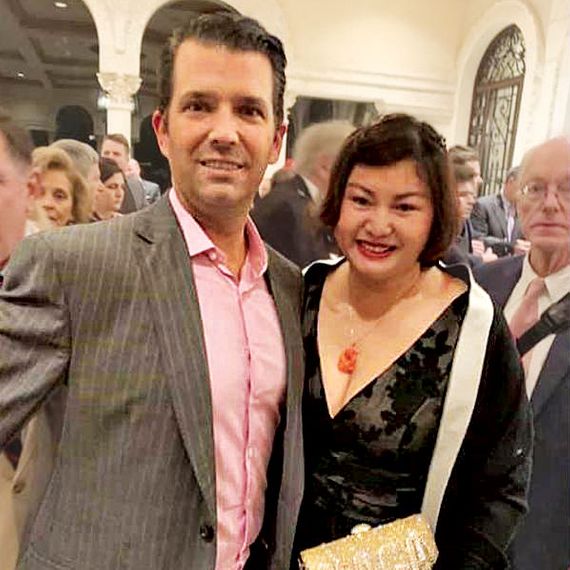

Yang’s social-media feeds, on Facebook, Instagram, and the Chinese platform WeChat, were similarly full of advertisements for her proximity to Trumpworld. There she was, posing with Don Jr. at Mar-a-Lago.

There she was with Eric. There she was with Brad Parscale, and Elaine Chao, and Sarah Palin, and Sebastian Gorka. There she was with Trump himself in February, grinning in a party snapshot at his golf club in West Palm Beach. The occasion would turn out to be disastrously perfect: the Super Bowl.

“How does a woman like that end up at Mar-a-Lago?” wonders Jose Lambiet, a longtime gossip columnist and chronicler of the Palm Beach scene. The answer, he adds, is self-evident: She paid. Yang’s offense was not daring to enter but being too blatant in her aspirations. But Trump is not judgmental about social climbers. “That’s something that Trump never gets credit for,” says Lambiet. “In his infinite greed, he doesn’t discriminate.” Although that assertion might sound bizarre to the rest of America, by the standards of Palm Beach, Trump is considered a sort of democratizer. After he bought Mar-a-Lago in 1985, from the estate of a cereal heiress, he battled the town government for many years over his plans to commercialize the landmarked estate, attacking the anti-Semitism of the old Palm Beach clubs. Trump triumphed, and now Mar-a-Lago is open to anyone who can afford the price he charges to bask in his company. Trump, always alert to an opportunity, hiked the joining fee to $200,000 immediately after his election.

Yang saw the opening and pushed her way through, with a determination that would later look a little suspicious to some partygoers. She apprehended, maybe even more quickly than many native-born Americans, the way the mechanics of political ascent have changed under Trump. Influence once worked through campaign donations and winks and nudges, but this president has opened a more direct route. If an individual gives $5,600 to Trump’s campaign, the maximum allowed, that contribution is publicly recorded and regulated by laws, including one that bans donations that flow from overseas. If the same person pays the Trump Organization the $200,000 it costs to join Mar-a-Lago, that’s perfectly legal. And if that person just wants to buy a benefit ticket, the cost of which will partly go back to Mar-a-Lago in the form of rental and catering fees? Party on.

Because it is a private club, there is no way to know exactly who is going into Mar-a-Lago and what is going on inside. But every once in a while an errant signal leaks out. In 2017, for instance, a Mar-a-Lago member posted a picture of himself posing with the military officer carrying the nuclear football.

Had it not been for a preposterously improbable chain of events — some not of her own making — Yang’s activities would probably have gone unnoticed. No one would have known the original source of her (relative) wealth, a chain of strip-mall massage parlors, and her reputation wouldn’t have been ruined by widely reported allegations of involvement in prostitution, campaign-finance violations, and maybe even spying (all of which she denies). She wouldn’t be suing the Miami Herald for defamation, accusing the newspaper of pursuing the “playbook for the anti–President Trump manifesto.” And she wouldn’t be banished from Palm Beach, lying low in a locale her lawyer won’t disclose.

“They are always making up news about me,” Yang complained to me over the phone one day this spring. “I am just so tired and so sick.” Soon afterward, the Herald reported that Mar-a-Lago and Trump’s reelection committee had been subpoenaed as part of a broadening FBI investigation of Yang. The winter season was over, and the heat was only rising.

For all their snobbery, Palm Beachers have an understanding that it is best not to pry into the sources of their neighbors’ wealth. The island’s residents have included the reputed former bootlegger Joseph Kennedy and the Ponzi schemer Bernie Madoff as well as countless ex-royals, ex-mistresses, and future convicts. One of its current grandes dames is the widow of the mobbed-up sleaze merchant who founded the National Enquirer. Yang was unusual, though, in the velocity of her ascent and her chosen propellant, the volatile politics of Trumpism. Her social-media posts were full of adulation for the “people-first president,” as she called him in Chinese, and punctuated by emoji: full hearts, flexed biceps, clenched fists. To Yang, Trump’s shamelessness served as both an inspiration and a license: to make a move, to crash the party, to invent a place in society.

Before she fled Palm Beach County, Yang lived about a dozen miles and an incalculable social distance from Mar-a-Lago, across the waterway that separates the island from the real Florida—the sunbaked flatlands of the state’s interior. She owned a tile-roofed house in the town of Wellington in a gated community where all the lots are set on little man-made coves. In a petition filed earlier this year to legally change her name to Cindy — her given name is Li Juan — Yang listed her occupation as “beauty school manager.” The document offers the bare rudiments of her biography: born in 1973 in a suburb of Harbin, China, a frigid northern city; graduated from the prestigious Wuhan University in 1994; immigrated to the United States about six years later.

Yang first lived in San Francisco, in a walk-up apartment in Chinatown, where she says she worked in the local Chinese-language media. After a few years, she moved to South Florida; she had friends there and liked the warm weather. Because the language barrier still presented a challenge, she went into cosmetology, an industry dominated by Asian women. “I never did massage,” Yang told me adamantly. “I did the facials and the nails.” In 2007, after a couple of years of toiling for other people, Yang had saved enough money to start her own business, Tokyo Day Spa & Massages. From a single spa, the business expanded and contracted through a half-dozen locations over the years, typically in upscale areas. Yang also owned the Tokyo Beauty & Massage School, which advertises its “hands-on training” in an “ever-growing field.”

The school currently lists an address that corresponds to the flagship location of the Tokyo Day Spa chain in Palm Beach Gardens, an area known for its golf-course communities. It is situated next to a yoga studio and a psychiatrist’s office. When I inquired, a young Asian woman wearing a medical-style smock handed me a laminated card with a picture of a geisha on it, promising “a touch from the Orient.” Down a narrow hallway were small, windowless rooms containing massage tables.

I didn’t get a massage, so I can’t say what happens inside the Tokyo Day Spa. What I do know is that once you start thinking about massage parlors, you notice them everywhere, especially in Florida, where they blend into the commercial landscape of osteopaths and pain clinics and salt therapy and physical therapy and spiritual therapy. “It’s a common way to become an entrepreneur if you have cross-national connections,” said Rochelle Keyhan, a former prosecutor who heads Collective Liberty, an advocacy group that investigates human trafficking. Keyhan told me that some Asian spas are actually just spas, some are outright brothels, and some occupy a “gray area,” performing both legitimate and sexual services. But she said they frequently exploit low-paid and often undocumented immigrant workers. The women are recruited from abroad or from the Chinatowns of San Francisco and New York, often via deceptive posts on Chinese-language social-media sites like WeChat. Physical force is rare, but once women are in the network, they may be imprisoned by debt and cultural isolation. They sometimes live in the spas. Masseuses may be told it is their choice if they want to sell sex. But they are working for tips.

One indicator of the industry’s prevalence in South Florida is the existence of Woody McLane, who advertises his services as a massage-parlor real-estate broker. When I met him at a diner near his home in Cooper City, McLane, a paunchy man with big square glasses, told me he was in the coin-laundry and collections businesses before he started frequenting massage parlors, where he met his current wife and found a new line of work.

“There’s a seamy side to the business — everyone jokes about happy endings and whatever — but I try to look beyond that to their work ethic,” McLane said. He told me much of his brokerage business involves matching sellers with women who have amassed enough cash to finance the $30,000 or so it costs to buy a spa. McLane had dealt with Yang — she was a well-known figure in the industry — but she operated at a higher level. “She was not cut out of the same cloth as 99 percent of these people,” he said. “The nicest, busiest street and the best location on that street — that’s where you’d find her.”

McLane told me Yang “prided herself on running a legitimate massage school” and said hers was “the preeminent one in South Florida.” That may not be much of a recommendation. Keyhan told me massage schools can be a key part of trafficking networks, allowing newcomers to obtain the necessary state licenses. “Florida has become the new mill,” she said.

Xiaoqi Wang, another Republican activist in Palm Beach County who got to know Yang during the Trump campaign, told me Yang’s business model was to open a Tokyo location and then flip it to her students once it was established. Keyhan said that’s a common pattern — a way for those at the top to cash out and distance themselves from legal risk. She also said that a nice location means little. “They’re presenting an air of legitimacy,” she said.

“Their customers are businessmen wanting a safe, seemingly consequence-free form of purchasing sex.”

When I asked McLane what proportion of the spas he dealt with offered sexual services, he wrinkled his face and guessed 80 percent. “A lot of the owners of these spas, they don’t want to be the happy-endings place,” he said. “But a customer comes in and they close the door … Who the hell knows what happens in that room, Andrew?” McLane told me that if I wanted to do further research, I should check out a subscription website called Rubmaps (motto: “Find your happy ending”), where men in search of prostitution post reviews. The site lists 1,425 massage parlors in the state of Florida, broken down by location, along with individual masseuses.

In March, the Herald reported that reviews posted on Rubmaps indicated at least some women working at Tokyo Day Spas had offered sex. The paper also cited a 2016 post on Yelp, in which a reviewer complained that a Tokyo Day Spa worker had asked her husband if he “wanted a hand job.” A Yelp commenter named “Cindy Y.,” identified as the “business owner,” replied with a profuse apology, writing, “We do not offer those kind of service.” The Herald also reported an allegation from an anonymous former Tokyo Day Spa employee, who said she told police her workplace was a front for prostitution. That story is now the subject of Yang’s defamation lawsuit. Her complaint claims the article is “fake news propaganda,” full of “conjecture, innuendo, and xenophobia.”

Yang wanted to get out of the massage business. In 2016, McLane said, she contacted him to say she wanted to sell her school and her spas as a package. “She always talked about big, big numbers,” he said. Her asking price, he recalled, was $400,000 — a ridiculous sum by the standards of the local massage industry. Since then, Yang appears to have closed or sold her spa properties one by one.

Friends say Yang was always seeking a more glamorous existence. She dabbled in side interests like real estate and fashion, pursuing them with feverish intensity until she got bored. “She has such a desire for high-cost things, for being excited, being among successful people,” said Cliff Zhonggang Li, a South Florida tech entrepreneur who became close to Yang through Republican politics. “She is also very much a dreamer.” Li said she once tried to bring a Silicon Valley–based “innovation channel” called Ding Ding TV — imagine TED but in Chinese — to Florida. Yang told him she admired Wendi Deng, a woman in the orbit of billionaires and prime ministers. “She is a very sharp person, and she has a talent to figure out what you want. It’s like a sixth sense of what you’re up to, and she will feed that,” said Li.

This was during the period when China’s ruling class was rapidly acquiring immense wealth and looking for brokers who understood America to help them invest in it. Around 2015, Yang tried to set herself up as an art dealer via a company called Fufu International. The gallery’s website — which had an address that corresponded to one of her spas — displayed pictures of Yang at art shows and described an event attended by Chinese collectors during Art Basel Miami Beach.

To further her connections back home, Yang got involved with a community organization with links to the Chinese government, the Florida chapter of the China Council for the Promotion of Peaceful National Reunification, which advocates for the mainland’s position on Taiwan. She established her own small nonprofit called the Women’s Charity Foundation, which put on events like a Chinese beauty pageant.

“She likes to show off. She wants to go to all the groups and be part of it, be somebody,” said Wang. “When she talks to me, I feel like all the purpose in her life is making money. I don’t really think she has a strong opinion about any issues.”

Yang’s interest in politics was mild at first. She attended the 2015 kickoff rally for Jeb Bush’s presidential campaign, but when Trump started winning primaries, something clicked. Yang posted photos of a local event for Republican women on her Facebook wall.

“The new life will start,” her caption read.

Yang’s introduction to politics happened over WeChat. The platform plays an overarching role in China: Imagine Facebook if it were also what you use to bank, buy groceries, and book a doctor’s appointment. In 2015, Li founded a WeChat political-discussion group that quickly developed a conservative following. “The thing was like a fire,” he said. Because Chinese rules limit WeChat groups to 500 members, Li’s soon fathered many offshoots. The Republican National Committee noticed the online activity and encouraged Li’s efforts to start a national political organization. The WeChat discussion also drew in Yang. Li became her political mentor and collaborator.

Over a long lunch at a strip-mall Thai restaurant, Li told me he was “an IT guy” and a former pro-democracy activist who left China after Tiananmen Square and later gravitated toward Republican ideas about free enterprise and affirmative action in education. He said he was initially wary of Trump — he was a Jeb! Supporter — and had to talk himself into overlooking the nominee’s radical rhetoric about trade and immigration. But Yang had no qualms. “She was fascinated by Trump.” Li said. “Cindy was falling in love with the president, not because of policy. When people are cheering and getting excited, that gets Cindy excited.”

While Li had ideas, Yang had contacts. She put together a well-attended Fourth of July gathering at an apartment she owned overlooking Biscayne Bay in Miami, where Li addressed the local Chinese community’s leaders. Their organization staged many campaign events: a group trip to a Trump rally in Fort Lauderdale, a protest at a Tim Kaine appearance, a screening of a Dinesh D’Souza movie called Hillary’s America, a day of “deplorable fun” at a park with a gun group.

That July, Yang was invited to attend the Republican National Convention in Cleveland as part of an Asian-American delegation led by Li. Its members wore matching white golf shirts embroidered with the party seal and make america great again. On posts to a WeChat forum she was active in, Yang rhapsodized about Trump’s speech. “I always think I’m a lucky person because I’ve seen many great moments,” she wrote in Chinese, saying the spectacle of balloons and confetti reminded her of watching the Chinese National Day military parade from the viewing platform at the Beijing International Hotel back in 1999. The American Dream, she wrote, was to dare to believe that people like her could play a role in government.

“I once thought that politics is a man’s world,” Yang wrote. “History is always changing. What’s the distance between man’s ideals and woman’s dreams?”

Yang attended Trump’s inauguration, where Li organized a party at the Mayflower Hotel. She appears to have spent a decent portion of 2017 in China, getting married to a furniture-factory owner whom she’d met through a mutual friend and making new business connections. Inevitably, this brought her into closer contact with the ruling Communist Party. The party has always been intertwined with the private sector in China, but controls have tightened under Xi Jinping, the country’s increasingly authoritarian leader. He has sought to reinvigorate a strategy known as the “united front,” under which every element of society — government, the military, business, academia — comes together to advance patriotic interests.

A Communist Party organ called the United Front Work Department strives to promote the ideology at home and abroad. Xi has called the strategy a “magic weapon,” while an increasing number of analysts outside China see it as his tool for enforcing loyalty to the party line, particularly within the overseas diaspora. Peter Mattis, a former CIA analyst who is now a fellow at the Victims of Communism Memorial Foundation, says it is common for China to work subtly through business deals. “The point of the United Front work,” Mattis said, “is to ensure that things like political activity on behalf of the party and moneymaking come together.”

When Trump took office, there was widespread enthusiasm for him in China. “The Chinese just love to have somebody breaking the existing system,” said Li. “Also somebody like Trump, who is a little bit of an authoritarian figure, fits that culture very well.” Early in his presidency, Trump invited Xi to a summit at Mar-a-Lago, where he said they “developed a friendship.” The notion that the president of the United States had a private residence that was open to paying visitors was mind-boggling to the Chinese, whose leaders rarely appear in public settings, let alone pose for selfies. The business class was eager to figure out how to meet Trump. “You have to know the Chinese mentality,” Wang said. “They just feel, Okay, if I spend $100,000 to take a picture with the U.S. president and then come back home and put the picture on the wall, I can make maybe $10 million, because that connection is important in China.”

In the summer of 2017, a route into Mar-a-Lago opened for Yang. Trump had refused to condemn the white-supremacist rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, prompting almost universal condemnation and a wave of charity-benefit cancellations at Mar-a-Lago. The holes in its calendar were filled by more politically themed affairs, like a Celebrating Trump party thrown by a group of Palm Beach socialites called the Trumpettes, who wear matching sashes. (“I was so angered by the ridiculous, stupid comments that were made against President Trump,” founder Toni Holt Kramer told me. “And my event, thank you very much, has been the hottest event on the island the past two years.”) At these parties, there was always a slight chance you might run into Trump himself. And you didn’t have to trace your bloodline to the Hapsburgs to score an invitation.

Yang started to escort guests to events at Mar-a-Lago, such as a Safari Night party for a youth charity. “She is a really good businessperson,” said Wang, who helped to organize a children’s Chinese-dance performance at Safari Night. “She saw an opportunity to get into Mar-a-Lago, and also if she buys the table, she can make money.”

Soon after, Yang started bringing visitors to Republican campaign fundraisers as well. This created a potential problem. Although anyone can attend political fund-raisers, only citizens can make the contributions required to get in. Starting in late 2017, Yang, previously only a small contributor, started making large donations to various Trump-campaign committees, as did her new husband and her parents, who also lived in Florida, amounting to some $70,000. Some Tokyo Day Spa employees gave thousands more, raising the possibility that straw donors had been illegally reimbursed to get around contribution limits.

In December 2017, Yang traveled to New York for a Trump fundraiser at Cipriani. Yang was one of several people who brought groups. VIP tickets were priced at $2,700, while a formal photo with the president required a $50,000 contribution. Yang enthusiastically reported on the event to her WeChat group, describing Trump’s explanation of his China policy and his laudatory words about Xi. “President Trump is one of the most trustworthy and honest US presidents!” Yang posted on WeChat that month. “He always tries his best to carry out campaign promises.”

Ten days after the Cipriani event, Yang filed to incorporate her tourism company, GY US Investments. Within months, the company’s website was promoting upcoming Trump-campaign fund-raisers in Texas and Ohio as well as various other networking and business opportunities, such as the federal EB-5 program, which offers green cards to foreigners in return for investments. On the site, she identified herself as a member of Mar-a-Lago. The club does not disclose who belongs, but I was told that Yang did in fact gain membership privileges in return for offering assistance to a Chinese car-factory owner who paid the $200,000 fee to join. (“The guy is loaded, a billionaire,” said Li.)

The first big night for Yang’s new tourism company was the Truth About Israel Gala. Its organizer, a Boca Raton communications executive named Steven Alembik, had announced the event immediately after Charlottesville. “Somebody needs to take a stand here and do something,” he told the Palm Beach Post. “My president is my president.” But his planning was sloppy. Alembik didn’t even file to form a charity until nine days before the party. (Financial documents filed after the event indicate it had just $900 in net income.)

Alembik declined to discuss the party, but others told me Yang had bailed him out financially. “You go to Steve Alembik and you become StubHub,” said Sid Dinerstein, a former chairman of the Palm Beach County GOP, who attended the gala. “And I will tell you other Asian people are looking to do the same stuff.” In fact, Yang tapped into a network of Chinese promoters who market elitist travel experiences. Invitations to Mar-a-Lago events would be packaged and resold to Chinese buyers at enormous markups, often with hilariously misleading rebranding. According to a web posting unearthed by the watchdog group the Campaign Legal Center, the Truth About Israel Gala was marketed in China as a “Private Estate Presidential Meeting” with a ticket price of $56,000. The post promised a “one-on-one photo” with Trump.

Although Yang advertised the party as a triumph, it was something of a debacle. Many of the Chinese guests were furious that Trump hadn’t shown up as expected. The wealthy investor who bid $21,000 for portraits of Trump and the First Lady sailed his yacht out of the Palm Beach marina without paying, citing concerns about the charity’s tax-exempt status. (Alembik would later be driven out of Florida politics, at least temporarily, after hurling a racial slur at Barack Obama on Twitter.) Yang’s behavior alienated many of the friends she’d met through local politics, like Li and Wang. But she was moving up. She told everyone she was selling her spas and relocating to Washington.

Yang wrote on WeChat about several trips to the capital in 2018. She attended a White House ceremony commemorating the Chinese New Year and participated in meetings with Cabinet members Elaine Chao and Wilbur Ross. “I’ve been invited to the party at the W Hotel next to the White House tonight,” she posted the day of last year’s midterm elections, “and I’ve attended meetings at the White House many times. Everyone has opportunities.”

Yang also seems to have been moving in rarefied circles in China. She traveled home to attend the Boao Forum, a conference modeled on Davos, where Xi delivered the keynote address. By this time, though, China’s rulers were starting to grow alarmed about Trump’s threats of punitive new tariffs. “Trade wars are good, and easy to win,” Trump tweeted that March, and he soon showed he was serious.

That marked the beginning of a new phase of confrontation. But Yang was still trying to reconcile her belief in China’s rising power with her love of Trump. “Trump is a businessman. His logic is very simple, ‘We are no longer suckers of the world,’ ” Yang posted to WeChat in June 2018, right before the first round of tariffs went into effect. “From the perspective of a CEO, it’s completely right to think so, but the problem is that the world has been spoiled by the US, so there is no easy way for the US to be mean to the world, especially China … Actually, the US has also been spoiled by the world. It has been bossing the world for a century. So it’s not easy to let it step down from the throne.”

I wanted to ask Yang about the chain of events that brought her new life to a disastrous end, but she was reluctant to talk. “She’s a broken woman,” explained her spokeswoman, Karyn Turk. Then, as I was driving through a housing development in Florida, Turk let me know Yang was ready. I pulled over and called from a patio table next to a deserted community pool. “My English is not good,” Yang said. She tried to articulate what had attracted her to Trump. “I just feel that’s something special for me, that’s why,” she said. “I love the party. I was just excited for that.”

When I started to ask about the other kinds of parties, the ones she charged for, Yang grew agitated. “Everything was new to me,” she said. “I was just a volunteer.” Soon Yang was sobbing. “That is why I don’t want to talk. It’s just making me very sick. I just feel so horrible.” Then she hung up.

Yang told me if I wanted more answers, I should talk to her spokeswoman. So a couple of hours later, I met Turk at a restaurant in Delray Beach along with her husband, Evan, who is Yang’s attorney. They said they met Yang through the Mar-a-Lago scene. Karyn, who is blonde and chipper, won the 2016 Mrs. Florida pageant and was active in Trump’s campaign, often appearing at events in her sash and tiara.

“Who doesn’t like to go to a charity event and post a selfie?” Karyn asked. She told me she felt immediate empathy for Yang, having gone through her own social-media controversy. Evan shot her a glance. “It’s okay,” she said. “If you Google me, it’s the first thing that comes up.” I did. Evan’s ex-wife had sued Karyn in 2017, claiming she had spread false rumors about her on Facebook and had threatened to hit her with a Louboutin stiletto. Anyway, the suit was dropped in February, and memories are fleeting in Florida, where people go for reinvention. “I think we’re all social climbing,” Karyn said. “That’s a bipartisan — that’s a human — thing. We’re all looking to be the best version of ourselves that we possibly can. So you’re now going to chastise people for wanting to make their lives better by making better friends, by going to better parties, by buying something nice for themselves?”

The incident that knocked Yang off the ladder had nothing to do with her, at least directly. Last November, acting on a tip from investigators working on a broader human-trafficking probe, local police in Jupiter, Florida, put a strip-mall massage parlor under surveillance. Over eight days, officers observed many customers coming and going, almost all of them men, including one celebratory group of eight in a golf cart. The police found that the business, Orchids of Asia, had numerous positive reviews on Rubmaps. An inspector from the State Health Department who was trained to investigate human trafficking was sent in. Inside, she found three women, including a nervous manager. Two tiny rooms in the spa were outfitted like a dormitory with made-up beds and dressers full of clothes and toiletries. After the inspector left, one of the women who worked there furtively tossed out a trash bag that was found to contain semen-smeared napkins.

The Jupiter police then took an unusual step, obtaining what is known as a “sneak and peek” warrant. Using the pretense of a bomb threat to the mall, they evacuated Orchids of Asia and installed hidden cameras in its ceiling. For five days, they watched the activity inside. On the second day of surveillance, a white Bentley pulled up and discharged a passenger, an older man in a blue baseball cap. He went into the spa and, according to a police report, was sexually serviced by a pair of women. Afterward, police used the pretext of a traffic violation to pull over the Bentley. The alleged customer produced identification. It was Robert Kraft, the owner of the New England Patriots — a friend of Trump’s and a frequent Mar-a-Lago visitor. He was quite far from the apartment next to the Breakers resort that he used during the social season, some 40 minutes away in Palm Beach.

The operation was ongoing, so Kraft was allowed to drive on after the phony traffic stop. Apparently, the brush with the law didn’t spook him, because the next morning he allegedly returned to the spa for another session, just hours before he watched the Patriots win the AFC championship in Kansas City.

Two weeks later, the Patriots played in the Super Bowl. Trump threw a party at the Trump International Golf Club in West Palm Beach. Yang was there, strategically positioned in a seat adjacent to Trump’s roped-off viewing area. When the president posed for a picture with one of the Trumpettes, Yang poked her face into it. “That photo was really rudely taken,” said Kramer, the Trumpettes founder, who asked me to be sure to mention her new memoir, Unstoppable Me. “There’s no cure for stupidity, and there’s no cure for lack of class.” (“I don’t know why all these women now want to pretend that another woman, who they were sociable with and liked, they know nothing about,” Turk said in reply.)

Soon afterward, Kraft was charged with two counts of soliciting prostitution. He maintains his innocence, and his attorneys recently persuaded a judge to throw out the video surveillance on the grounds that police had overstepped. But the consequences for Yang were devastating. Orchids of Asia operated as a Tokyo Day Spa before Yang sold it off in late 2012. She claimed she had nothing to do with the current ownership, and that seems true. But once the Herald dug up that Super Bowl picture, there was no containing the lurid story. Investigative reporting, driven by local newspapers and Mother Jones, exposed her boasts, her businesses, her questionable campaign contributions. Within South Florida’s Chinese-American community, judgment was scathing. People called her “Yang Laobao” — the latter word translating as “madam,” and not in the respectful sense. A Herald reporter even tracked down her mother at a condo Yang owned in Royal Palm Beach. “She likes to make people jealous,” she said disapprovingly in Mandarin. “It was all because of the parties.”

Her mother was right. The fact that she didn’t own Orchids of Asia was easily elided. Yang had made herself too deliciously symbolic. Among liberals, though, there was some disagreement about what she stood for: the absurdity of this political moment, or its corruption? Democrats in Congress called on the FBI to investigate Yang, raising the possibility that she had been acting as a foreign agent. Yang tried to defend herself in a shaky round of television interviews, saying the scandal was all “fake news,” but then she packed up her house and sold it, seemingly in great haste. She was ruined in Palm Beach. And that led to the tale’s final twist: the spy plot.

One of the events that reporters discovered Yang was promoting was an “International Leaders Elite Forum” at Mar-a-Lago, which was to feature a speech by Trump’s sister Elizabeth. In reality, the “forum” was a reprise of the previous year’s Safari Night. “I was shocked,” said Terry Bomar, the minister who runs the Young Adventurers charity, which the event was supposed to benefit. He said he had been talking to Yang about using the party’s proceeds to sponsor a children’s trip to the Great Wall. “I certainly don’t think she was nefarious,” he said. “She probably thought she was being a smart businesswoman.” Nonetheless, with the controversy, Bomar canceled the party.

This news may not have reached China, because on March 30, the date Safari Night was supposed to be held this year, a woman named Yujing Zhang showed up at Mar-a-Lago. Trump was off playing golf when she arrived, but he was staying at the club that weekend, which meant the Secret Service had tightened security. At a checkpoint outside the gates, Zhang presented her Chinese passport. The agent on duty thought she was saying she was there to use the pool. Her name was not on the access list maintained by Mar-a-Lago’s private security, but there was another member of the club named Zhang, so she was presumed to be a family member. (Zhang is one of the most common names in China.) A valet took her to the reception desk, where she attempted to convey that she had arrived for a “United Nations Friendship Event.” There was, of course, no such event.

When Secret Service agents confronted her, Zhang attempted to show them an invitation on her phone, but it was in Chinese, so they couldn’t read it. When she grew angry, she was taken to a Secret Service office for further questioning. Zhang told the agents she had come to Mar-a-Lago to discuss Chinese-American relations with a relative of the president. She said she had secured her invitation from a man named Charles, with whom she had only conversed over WeChat. The Secret Service agents searched her bags and found four phones, a laptop, an external hard drive, and a thumb drive, which they stated in a sworn affidavit was found to contain “malicious malware.” More electronics and $8,000 in cash were later found in her hotel room. Zhang was charged with trespassing and making false statements and held without bail on suspicion of espionage.

In fact, Zhang really did have an invitation, from Cindy Yang. A middleman known as Charles Lee, who, according to the South China Morning Post, has several other identities and a history of being accused in swindles, along with Communist Party ties, had rebranded the rebranded party. Zhang had a receipt showing she had paid the equivalent of $20,000 for her travel package. Federal prosecutors have backed off the claim that her thumb drive contained malware, but Zhang is still being held in detention as she awaits trial on charges that could result in a five-year sentence. She recently fired her public defender and plans to represent herself.

It is hard to know whether Zhang was up to something sinister or is merely the victim of an extraordinary cultural mishap. “This lady who tried to rush into Mar-a-Lago is apparently a moron and not some kind of a spy,” said Cliff Li, a conclusion shared by some China experts. Yang claims she didn’t know Zhang, which seems plausible, or Charles Lee, which seems less so, considering she posed for a picture with him at a Mar-a-Lago party in 2017. Amid the climate of rising suspicion of Chinese spying activity, though, even some of her previously anodyne-looking associations now seem suspect. For instance, remember the Florida chapter of the China Council for the Promotion of Peaceful National Reunification? According to a U.S.-government report, the organization is “directly subordinate” to the United Front Work Department, Xi’s purported weapon for overseas influence. The chapter president attended the fund-raiser at Cipriani, where she took a picture with Kellyanne Conway.

“The United Front is trying to infiltrate,” Li acknowledged. But he laughed off the notion that Yang was a foreign operative. “She is really not a complicated kind of person.” Of course, you never know: Maybe she was what the Soviets would have called a “useful idiot.” Or maybe being overbearing and oversharing was just a clever element of Yang’s cover as a spy. In the current climate, Chinese-Americans are caught in a prejudicial vise: If they look innocent, maybe that’s because they’re really very guilty. Susan Shirk, a former State Department official who heads the 21st Century China Center at UC San Diego, told me she was worried about an “anti-Chinese version of the Red Scare.” Shortly after Zhang’s arrest, the Committee of 100, an organization of eminent Chinese-Americans, raised similar fears, saying citizens were being “targeted as potential traitors, spies, and agents of foreign influence.”

Li told me he hears “a lot of McCarthyism” coming from both the Trump administration and the Democrats. Although he acknowledges that he originally encouraged Yang’s efforts to promote Trump to China, he recognizes the outcome has been disastrous. “Trump tourism really gives us a bad name,” he said, adding that he is now toying with supporting a Democratic candidate, Andrew Yang. Li claimed he tried to caution Yang, telling her about John Huang, the Chinese-American fund-raiser who channeled foreign donations to Bill Clinton’s reelection campaign and ended up pleading guilty to a felony conspiracy charge. “I made such a big, compelling case to her,” Li said, “that if you get a lot of money, you’re going to get yourself in jail.”

Yang is the subject of multiple FBI investigations, according to the Herald. One is focusing on campaign contributions, while a counterintelligence probe is more broadly examining Chinese political activities around Mar-a-Lago. Meanwhile, Kraft may end up walking away with his life and reputation intact. (On June 20, he was presented with an award by Israeli prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu.) Like so many others who have tried to emulate Trump, Yang has discovered the limits of what she can learn from the master. Trump may be able to mix business and politics and foreign intrigue, never seeking permission or apologizing and always getting away with it. But America does not reward its hucksters equally. Cindy Yang was allowed into the club, only to find that it contained another door, and only one man can pass through it.

*This article appears in the June 24, 2019, issue of New York Magazine. Subscribe Now!