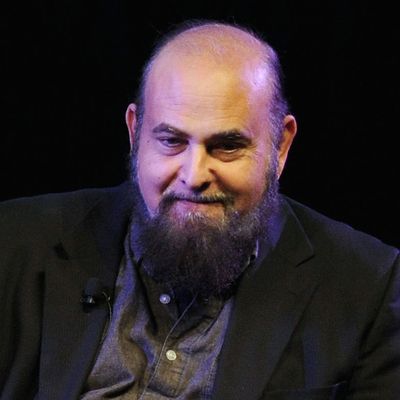

With the possible exception of national security, there’s no area of public policy in which politicians have gotten more things tragically wrong than in the nexus where drug-control efforts meet the criminal-justice system. The United States is only now beginning to dig itself out of the destructive rubble of the War on Drugs and its evil handmaiden, mass incarceration of low-level drug offenders. And we’ve just lost one of our most valuable guides on the road to more sensible policies, Mark Kleiman, who died this week due to complications from a kidney transplant. During his many years as a professor at UCLA and then at NYU, Kleiman was simply irreplaceable.

Back in my own days as a policy wonk and sometime writer about crime policy, Mark was the one expert in which I had unshakable faith, as did an awful lot of other people from diverse backgrounds and outlooks. While he was a sometimes sharp-elbowed partisan in politics, he was unfailingly decent and generous in helping those who needed the benefit of his vast erudition in a tricky field, as Vox’s German Lopez testified in his own posthumous appreciation:

Kleiman was also known for being incredibly kind and helpful. When I started at Vox in 2014, I found myself covering criminal justice and drug policy issues — especially marijuana legalization, which was taking off at the state level — at the national level for the first time in my career. I had a lot of really basic questions.

When I called, Kleiman would always ask how I was doing, making sure things were going well at Vox and inquiring about what I was working on. It was a small thing, but exchanging details about our newest projects made it clear he actually cared about the work; it wasn’t just a transactional interview.

His fans were by no means limited to those who shared his Democratic politics; both Reason and National Review have already published takes on his contributions to the policy world. At NR, Gabriel Rossman, calling him “America’s greatest thinker on drug policy,” had this to say about his influence, which is just now beginning to be fully felt:

Although he was an extremely partisan Democrat, Kleiman recognized the need to build a bipartisan consensus on drugs and criminal justice. To that end, he cooperated with the conservative criminal-justice group Right on Crime, wrote for National Review using arguments and frames targeted to its readership, and generally forged collegial friendships with people who were open to his ideas about criminal justice and drugs regardless of serious disagreement on other issues.

Kleiman was best known for his empirically-based takes on drug addiction and the economics of the drug trade. In that capacity he was a regular critic of what he denounced as a “brute force” mass-incarceration approach that failed to reduce drug-related crime and inflicted untold collateral damage. But he also warned against simplistic drug-legalization regimes that paid insufficient attention to the realities of addiction and to the risk of creating corporate drug cartels under the likely domination of Big Tobacco. In his last years Kleiman was a valued adviser to states (including New York) that were planning or implementing cannabis legalization.

But arguably Mark’s most valuable contribution over many years was the attention he paid to an issue that policy-makers in both parties had systematically ignored in a rush toward inflexibly longer sentences and less probation and parole: how we reintegrate prisoners, particularly those with substance abuse problems, in a way that doesn’t simply exacerbate their problems, and in turn, society’s problems. He was constantly promoting practical efforts to implement and fine-tune post-prison supervision (with teeth, to deter backsliding) in a way that reduced time in the slammer but also recidivism. And though he was very committed to research on this subject, he was also very good at explaining the situation to non-specialists, as in an important 2015 article for Vox with two of his academic colleagues:

Consider someone whose conduct earned him (much more rarely “her”) a prison cell. Typically, that person went into prison with poor impulse control, weak if any attachment to the legal labor market, few marketable skills, and subpar work habits. More often than not, he’s returning to a high-crime neighborhood. Many of his friends on the outside are also criminally active. Maybe, if he’s lucky and has been diligent, he’s learned something useful in prison. Perhaps he’s even picked up a GED. But he hasn’t learned much about how to manage himself in freedom because he hasn’t had any freedom in the recent past. And he hasn’t learned to provide for himself because he’s been fed, clothed, and housed at public expense.

Now let him out with $40 in his pocket, sketchy if any identification documents, and no enrollment for basic income support, housing, or health insurance. Even if he has family or friends who can tide him over during the immediate transition, his chances of finding legitimate work in a hurry aren’t very good. If he’s not working, he has lots of free time to get into trouble and no legal way of supporting himself.

Altogether, it’s a formula for failure — and failure is, too often, what it produces.

Now that criminal-justice reform has become an ongoing (and rare bipartisan) cause at both the federal and state levels, we have an opportunity to get crime and punishment, addiction and recovery, right this time, before we lose another generation to death, ill health, and prison. Mark Kleiman’s work will likely be relevant for years to come, much as we will miss his provocative and constructively critical presence. May he rest in peace. He earned it.