Ever since the United States mistook a Twitter-addled con man’s publicity stunt for a presidential campaign — and then elected him to our nation’s highest office — calls for rethinking America’s approach to democracy have been at the forefront of public debate.

For Democrats, Donald Trump’s victory illustrated the importance of expanding popular sovereignty in the United States. After all, an America governed by majority rule would be one where Trump could never govern. The mogul’s victory was not merely contingent on the Electoral College, but also on the low voter participation rates of America’s poor, young, and nonwhite citizens. In a country where the non-voting public skews left, right-wing “populism” can’t compete unless turnout skews elitist. Thus, to American liberals, the best prophylactic against future Trumps is more democracy — which is to say, reforms that expand the electorate and render the government more accountable to the will of electoral majorities. To that end, House Democrats made a package of democratic reforms — including nationwide automatic voter registration, a revamped Voting Rights Act, and a ban on partisan gerrymandering in federal elections — their first legislative priority upon taking power. Since then, the party’s 2020 candidates have almost all unveiled their own platforms on democracy expansion.

But some took the opposite lesson from Trump’s triumph. For one contingent of political observers, the reality star’s victory seemed to be a symptom of too much democracy. After all, had the GOP’s establishment elites been free to appoint their preferred standard-bearer, Trump would have gotten no closer to the nomination than his “university” did to accreditation. And while Trump did lose the popular vote, he lost it by far less than one would hope, given his conspicuous lack of qualifications for high office. The peculiar ethnic and partisan dynamics of the U.S. might render Trump’s specific brand of demagogy less viable under more majoritarian rules. But his ability to even compete highlighted a fundamental flaw in popular democracy, one that also enabled Brexit, and the rise of majoritarian right-wing nationalist movements throughout much of Europe and Asia: in the absence of expert guidance and mediating institutions, the ordinary voter is cognitively unfit for self-government.

Politico recently summarized UC Irvine political scientist Shawn Rosenberg’s rendition of this argument:

Democracy is hard work. And as society’s “elites” — experts and public figures who help those around them navigate the heavy responsibilities that come with self-rule — have increasingly been sidelined, citizens have proved ill equipped cognitively and emotionally to run a well-functioning democracy …

[Democracy] requires a lot from those who participate in it. It requires people to respect those with different views from theirs and people who don’t look like them. It asks citizens to be able to sift through large amounts of information and process the good from the bad, the true from the false. It requires thoughtfulness, discipline and logic. Unfortunately, evolution did not favor the exercise of these qualities in the context of a modern mass democracy.

For reasons cited above, I find the notion that the U.S. government is suffering from a surfeit of democracy to be unintelligible. But those who rage against the twilight of the elites do get one thing right: Good government does require institutions that mediate between voters and state.

Rosenberg is correct that democratic self-rule asks too much of the isolated individual. And other advocates for “less democracy” are right to question whether direct elections are always the most effective tools for elucidating the public interest. Sometimes referenda enhance responsive government by isolating voters’ preferences on discrete policy issues from their broader partisan attachments (i.e., Medicaid expansion ballot measures are often a more reliable means of gauging public support for that policy in red states than legislative elections between pro- and anti-Medicaid expansion candidates). On policy questions that are abstruse or unfamiliar to the mass public, however, plebiscites may not empower “the people” so much as they advantage whichever interested party has the most money to spend on propaganda.

But these facts say less about the deficiencies of democracy than they do about about the insufficiency of elections — by themselves — to produce popular self-rule. The alternative to naive faith in the omnicompetence of the individual voter need not be an equally naive faith in that of unelected technocrats. The most vital mediating institutions in a liberal democracy are not those formed by elites to check the irrational appetites of ordinary voters, but rather, those formed by ordinary voters to check the avarice of elites. Democracy asks too much of the individual. But if individuals organize collectively, they can force democracy to give them a better deal.

Which is a fancy way of saying: To repair American democracy — and fortify it against future threats — Democrats must not only bring more Americans into the electorate, but also, more American workers into labor unions.

Democracy begins at work.

There’s a strong argument that giving ordinary Americans a say over how their workplaces are governed is just as fundamental to democracy as giving them the ballot.

These days, political liberty is often defined narrowly as the freedom to vote in fair elections. But in earlier eras of American history, genuine political freedom was thought to have a material component: To truly participate in self-government, one needed not only a voice in public affairs, but also a modicum of power in one’s economic life. Franklin Roosevelt articulated this principle when introducing his economic bill of rights in 1944, telling Congress, “We have come to a clear realization of the fact that true individual freedom cannot exist without economic security and independence.” This sentiment might have struck some of FDR’s fellow “economic royalists” as un-American. But the notion that self-government is impossible without a degree of economic autonomy was common among our republic’s founding generation. The historian Terry Bouton writes of America’s original grassroots revolutionaries:

[M]any Pennsylvanians believed that economic equality was what made political equality possible. They were convinced that “the people” would never have political liberty until citizens had the economic wherewithal to protect their rights. To them, concentrations of wealth and power led to corruption and tyrannical rulers, while widely dispersed political and economic power promoted good government.

… Farmers and artisans declared that the Revolution was about “the freemen of this Country” stating that “they do not esteem it the sole end of Government to protect the rich & powerful.” … [G]overnment should promote the interests of “the mechanicks and farmers [who] constitute ninety-nine out of a hundred of the people of America.” In short, the objective of the Revolution was bringing “gentlemen men … down to our level” and ensuring that “all ranks and conditions would come in for their just share of the wealth.”

The revolution’s elite architects had other objectives. But while they typically did not believe that all white men (let alone, all people) were entitled to political liberty, they agreed that one needed economic power to exercise such freedom. As Alexander Hamilton wrote in the Federalist Papers, “A power over man’s subsistence amounts to a power over his will.”

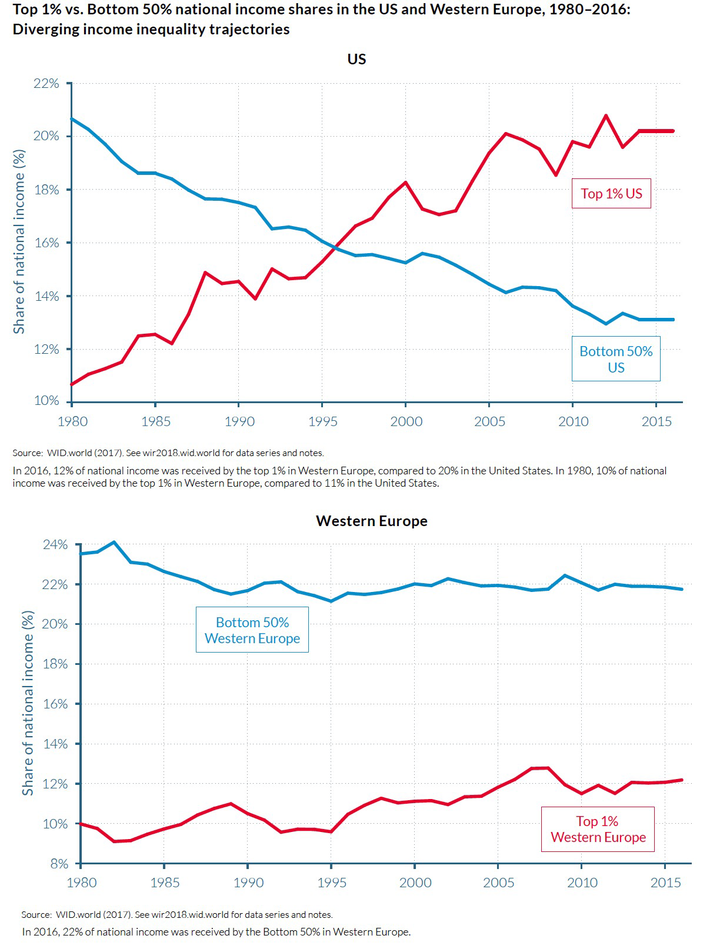

If we accept our founders’ premises, then the true measure of a democracy — which is to say, a system of government in which all citizens enjoy political liberty — cannot merely be how many offices its people get to vote on. Rather, to gauge how democratic a society is, one must examine how much power ordinary citizens have over the terms of their own subsistence, and how evenly economic resources are dispersed across the demos. Judged on these terms, it is clear that the contemporary United States is the opposite of “excessively democratic” — and that it will remain so, absent a revival of its labor movement.

In the founding era, classical republicans imagined that the great masses of ordinary (white male) Americans could attain the economic autonomy necessary for political liberty by becoming small landholders, or independent artisans. But the industrial revolution rendered that vision obsolete. Today, the vast majority of Americans are not self-employed, and spend the bulk of their waking hours answering to bosses who have power over their subsistence. In this context, most workers can only secure a degree of control over their economic lives by organizing collectively to check the power of their employers. Which is to say, they can only do so by forming unions.

That trade unions do, in fact, increase their members’ power over their own working lives is confirmed by the wage and benefits premiums that unionized workforces enjoy. But organized labor does not merely democratize individual firms; it also democratizes economic power throughout the economy. As America’s private-sector unionization rate collapsed over the past half century, the middle-class’ share of productivity gains went down with it. And a large body of economic research confirms that this is no mere correlation. When workers organize, they secure a voice within the “private governments” that rule their economic lives, and they (typically) use that voice to rationally advance their own material interests — which, most of the time, also advances the self-interest of most Americans (a.k.a. the public interest). In other words, by forming trade unions, ordinary citizens achieve much of what critics of democracy insist it can’t deliver.

Thus, even if organized labor did nothing to increase voter participation, or the responsiveness of elected officials to popular demands, it would still serve an indispensable democratic function by fostering the material preconditions for popular self-government.

Unions make electorates more representative.

Many items on the Democratic Party’s democracy reform agenda are aimed at making the American electorate look more like the American people. Automatic voter registration, a federal Election Day holiday, and felon enfranchisement are all aimed at reducing class and racial disparities in voter participation. And such reforms are laudable. But no plan for lifting America’s low voter turnout rates is complete without a plan for boosting its piddling rate of unionization.

As the Center for American Progress (CAP) has noted, the U.S. states with the highest unionization rates also have the highest rates of voter turnout, and the same correlation holds between nations. And the political science literature suggests this is not coincidental. As David Madland and Nick Bunker wrote for CAP in 2012:

A 1 percentage point increase in union density in a state increases voter turnout rates by 0.2 to 0.25 percentage points according to analysis by Benjamin Radcliff and Patricia Davis, political scientists at the University of Notre Dame and the State Department, respectively. In other words, if unionization were 10 percentage points higher during the 2008 presidential election, 2.6 million to 3.2 million more Americans would have voted.

Similarly, research by Roland Zullo, a labor studies professor at the University of Michigan, shows that self-described working-class citizens — whether unionized or not — are just as likely to vote as other citizens are when unions run campaigns in their congressional district. Yet when unions don’t run campaigns, working-class citizens are 10.4 percent less likely to vote than other citizens.

A similar pattern holds for communities of color. Voters of color are just as likely to vote as white voters in districts with union campaigns but are 9.3 percent less likely to vote in districts without campaigns.

A 2018 study of the electoral impacts of so-called “right to work” (RTW) laws lend credence to these findings. Such laws undermine organized labor by allowing workers who join a unionized workplace to enjoy the benefits of a collective bargaining agreement without paying dues to the union that negotiated it. This encourages other workers to skirt their dues, which can then drain a union of the funds it needs to survive. On the plus side, such state-level right to work laws provided political scientists at Boston University, Columbia, and the Brookings Institution with a natural experiment to test the relationship between unionization and electoral outcomes. By examining how voter turnout changed before and after the passage of RTW in a given state’s border counties — and comparing those shifts to the control group of adjacent counties in non-RTW states — researchers found that right to work laws are associated with 2 to 3 percent reduction in voter participation.

Separately, unions also appear to facilitate the kind of cross-racial civic solidarity that scholars like Rosenberg fear our species may be evolutionarily ill-equipped to achieve. Although the American labor movement has often been a bastion of white supremacy — one that channeled the “economic anxiety” of white male workers into causes like the Chinese Exclusion Act — it was also at the forefront of the Civil Rights Movement, and helped to keep the bulk of white workers in the Midwest in a partisan coalition with African-Americans for decades after backlash politics painted the non-union South red. According to that 2018 study, the passage of right to work laws is associated with a 3.5 percent drop in the Democratic Party’s share of the presidential vote. Which is to say: Had tea party governments not passed such measures in Wisconsin and Michigan, it’s plausible that the union movements in those states would have kept a critical mass of white non-college voters from chasing the siren song of white identity politics in 2016.

The proletariat needs lobbyists, too.

One testament to American democracy’s dysfunction is the cartoonish incompetence of its commander-in-chief. A less conspicuous — but more consequential — one is the chasm between popular preferences and public policy. The Trump administration’s decision to prioritize tax relief for corporate shareholders over new spending on infrastructure, public education, health-insurance subsidies, or addiction treatment in the middle of a historic drug overdose epidemic didn’t merely buck majoritarian opinion among Americans writ large, but also, among self-identified Republicans. And the same can be said of the White House’s prioritization of various polluters’ profit margins over the cleanliness of America’s air and water, or Congress’ perennial prioritization of the pharmaceutical industry’s profitability over the affordability of prescription drugs, or the myriad other ways that well-heeled interest groups overrule the bipartisan consensus of ordinary Americans in opinion polls.

One could attribute such policy outcomes to the median voter’s failure to meet democracy’s heavy demands; her struggle to sift through large amounts of information, and refusal to sacrifice her limited free time to the obligations of civic engagement. But the average American worker — and typical American CEO — are each working with the same archaic evolutionary hardware. The fact that the latter has proven so much more adept at using democratic freedoms to advance her interest is a function of resources, not psychobiology.

Influencing elections and legislative processes requires investments of time, money, and attention. Wealthy individuals and corporations can easily shoulder such expenses; ordinary voters can’t. For this reason, if the average House member betrays the interests of the oil company based in her district, she will see her voice-mail box fill up, and campaign coffers empty out; if she betrays her median constituent’s avowed desire to see carbon pollution more tightly regulated, by contrast, said voter probably won’t even notice.

This simple reality — that economic power is easily converted into the political variety — is an inherent constraint on popular sovereignty in all capitalist democracies. But trade unions help to mitigate it, both by reducing inequalities in economic power (as we’ve already seen), and by enabling working-class voters to collectivize the costs of political engagement.

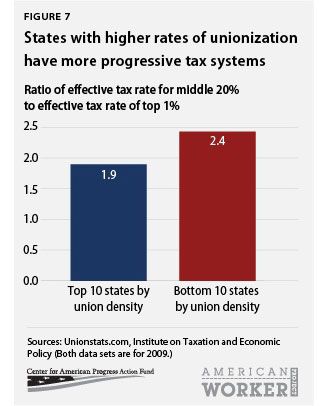

Of course, voters do not all interpret the world as vulgar Marxists would prefer. Class interests do not always map onto policy preferences. Nevertheless, there are some areas where majoritarian opinion across developed countries is quite consistent: Working people of all stripes tend to like it when the rich pay steeper taxes than they do. Meanwhile, as a general matter, most Americans also tend to evince support for increasing spending on the social safety net (although individual transfer programs can be unpopular). And U.S. states with high unionization rates do tend to have more progressive systems of taxation, and more generous levels of social provision.

In recent weeks, the Democratic Party’s top 2020 candidates have unveiled ambitious proposals for eroding legal obstacles to union formation and labor militancy in the United States. Many have separately released plans for fortifying American democracy. Given the broad public support for the objective of rolling back plutocracy — and the centrality of organized labor to actually realizing that goal — Democrats should make clear that the projects of reviving the union movement and restoring “good government” are one in the same.