Three summers ago, a worker stood up at “Q&A,” Facebook’s weekly all-hands, town-hall-style meeting, which is usually held on Friday afternoons in Menlo Park and livestreamed to its offices around the world — and aggressively closed to the public and press — to ask Mark Zuckerberg whether the company had a plan in case the public turned against it, like what had happened to the big banks a few years earlier.

Zuckerberg didn’t even know how to answer the question. That backlash won’t happen, he said, as long as the company keeps shipping products people like. Some conservative commentators had been accusing Facebook, with little evidence, of censoring their voices, but the company remained popular. Hillary Clinton, sure to be the next president, was shaping up to be a great friend of Facebook’s and of tech titans in general. In fact, there were few more reliable allies of Silicon Valley in national politics than the Democratic Party. Democrats and many of Silicon Valley’s leaders were partners on everything from campaign funding to voter-data programs. Sheryl Sandberg, of Lean In fame, had traveled to Clinton’s Brooklyn headquarters to talk about gender equality with the candidate and her staff almost as soon as the campaign launched in 2015. The following August, Laurene Powell Jobs, Steve Jobs’s widow, held an intimate dinner for Clinton and about 20 industry leaders, each of whom paid $200,000 to be there. Around that time, Sandberg was widely considered a contender to be Clinton’s Treasury secretary, and other Silicon Valley bigwigs, such as Google CFO Ruth Porat, were the subjects of Cabinet talk too. That spring, Apple CEO Tim Cook found himself on Clinton’s initial list of potential running mates, and on Election Night, Google chairman Eric Schmidt — who’d played an important role in guiding the party’s data operations since 2008 — walked around the Javits Center wearing a staff credential.

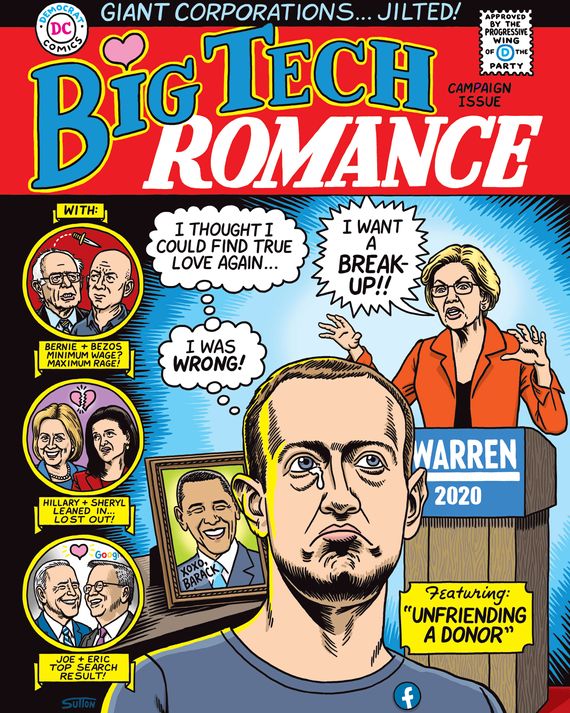

Three years later, things couldn’t look more different. Leaders of Silicon Valley and the Democratic Party are, if not exactly at war, in some ugly early stage of a protracted, high-powered, acrimonious divorce. A new phase of regulatory crackdown has delivered fines, like $5 billion for Facebook’s mishandling of user information (a slap on the wrist that caused genuine panic among other tech companies that can’t afford the same fate). This month, members of the House demanded personal emails from executives at Amazon, Apple, Facebook, and Google. But the split has also exposed the underlying marriage of party and industry as more a union of convenience than either side thought back in the Obama era, when liberals saw in the Bay Area a natural ally of technocratic progress. Perhaps no one had bothered to discuss the ideological details.

Broadly speaking, Silicon Valley remains socially liberal and anti-Trump. Its boards and executive floors are stacked with Obama-administration alums. But what once seemed like an intuitive mutual understanding between the emerging Democratic majority and the robber barons of the 21st century has grown into something more mutually suspicious, sometimes even hostile. Technologists no longer unquestioningly assume the more liberal party actually shares their values, and Washington Democrats are no longer willing to be seen by tech billionaires as know-nothing functionaries who can be counted on to do their bidding. In 2017, when a nationwide listening tour prompted widespread speculation that he was running for president, Mark Zuckerberg was asked about his political plans at another company Q&A. No offense to the presidency, he said, but I already run a community of 2 billion people. Today, tech leaders are baffled and angry that Democrats so routinely question their motives. Who do they think they are?

And while it took the 2008 financial crisis — and the decade of fallout that followed — to tear Democrats from Wall Street, the onset of their breakup with Silicon Valley happened much more abruptly.

This decoupling reflects the tarnished reputations of once-gleaming companies like Facebook, Google, and Amazon, still widely trusted but increasingly damaged, especially on the left, by public furor over election interference, monopolistic practices, and labor policies. It reflects, too, a more populist Democratic Party, which sees tech monopolies not as the swaggering future of corporate America but as a target for a revived antitrust movement. (“The fact that within the first five minutes of the first debate of the entire season, antitrust came up — how far are we from 2008?” asks Facebook co-founder and Obama 2008 “online organizing guru” Chris Hughes, who in May called for the company’s dismantling and labeled his Harvard roommate Zuckerberg’s power “unprecedented and un-American.”)

Partly it reflects the rise of the alt-right and increasingly open libertarian sympathies among leaders in Silicon Valley, along with the growing divide between some of those bosses and the rank and file, who are much less comfortable with Trump. (Elizabeth Warren was the biggest recipient of Google-employee campaign donations over the first half of 2019, even as she threatened to separate the company’s central businesses.)

But this isn’t just an ideological story or an inevitable one. Some blame for the breakup lies with the calculated maneuvers of just a few politicians on the rise and the blunders of a few big-money techies looking to play politics, with neither party willing to pay the deference the other felt was required. Democrats might’ve been a lot more willing to forgive the sins of Big Tech if its executives had performed even the smallest show of political humility or contrition in their responses to political scandals or in their outreach to candidates.

Or if some hadn’t been so shameless in their courting of Trump or their ham-fisted playacting of distance from Democrats in response to Republican accusations of bias — one leading industry group presented its Internet Freedom Award to Ivanka Trump in May, for instance. Complaining about tech leaders, the chair of one state Democratic Party told me that at this point, “the only way for them to redeem themselves is to write big checks, which they’re not doing.”

If the question about banks befuddled Zuckerberg at the town hall, it would’ve made sense to Warren, who, in private meetings on Capitol Hill as early as mid-2017, was explicitly comparing the country’s tech leviathans to the pre-regulation giants of high finance because of their information advantages over consumers and their D.C. influence. Over the next two years, she effectively made it politically impossible for her serious rivals to offer Silicon Valley outright praise. BREAK UP BIG TECH read a billboard her campaign put up outside San Francisco’s main Caltrain station this spring.

Last September, Bernie Sanders re-branded legislation from Bay Area congressman Ro Khanna as the “Stop Bad Employers by Zeroing Out Subsidies Act” (Stop BEZOS), aiming to pressure Amazon into increasing workers’ wages. Sensing trouble, Amazon calculated it would be worth back-channeling with Sanders’s staff and invited the Vermont senator on a warehouse tour even as he ratcheted up public pressure. Sanders pushed on, and in October Amazon announced a $15 minimum wage for its U.S. workers. Sanders got no heads-up, but the left felt empowered. The company was reluctant to play nice again if it meant another public capitulation. The next month, when Amazon announced its deal to place a second headquarters in Long Island City, it did no concerted outreach to progressive activists, figuring it already had sufficient support from New York’s Democratic mayor and governor, the latter having jokingly offered to change his name to “Amazon Cuomo.” As opposition to the deal soon mounted, both Cuomo and Mayor Bill de Blasio failed to get Bezos on the phone, instead only occasionally connecting with Jay Carney, the former Obama White House press secretary now running Amazon’s comms and policy arms. Amazon had enough of the leftward pressure and pulled out in February.

“Amazon came, Amazon left,” Warren crowed a few weeks later in Long Island City, announcing a new plan to “break up” the biggest tech firms (which would actually have regulators undo a series of tech mergers). “You know, that is the problem in America today — we have these giant tech companies that think they rule the Earth. They think they can come to towns, cities, and states and bully everyone into doing what they want.”

Not everyone in the party saw it like that. Among the 2020 candidates, none have tried having it both ways on tech more than Pete Buttigieg, the contender who could fit most seamlessly into Sand Hill Road tomorrow if he wanted to. Buttigieg was Facebook’s 287th user as an undergrad, knew Zuckerberg at Harvard, and hosted him in South Bend in 2017. He has criticized Google and appeared with striking Uber and Lyft drivers, but he has also raised money from or staged fund-raisers hosted by Netflix chief Reed Hastings; former Facebook exec Chris Cox; Uber’s Chelsea Kohler; Google’s Scott Kohler, John Flippen, Jacob Helberg, and Clay Bavor; Nest’s Matt Rogers; Quora’s Charlie Cheever; and Groupon’s Andrew Mason. Buttigieg also tapped a Square and Kleiner Perkins alum, Swati Mylavarapu, to run his finance operation and a former Google big shot, Sonal Shah, to lead his policy shop.

But even Buttigieg’s growing Silicon Valley financial network pales in comparison to the operations assembled for candidates in recent election cycles after the door between Big Tech and campaigns burst wide open with Obama in 2008 and the industry cemented its role alongside Hollywood and Wall Street as one of the party’s biggest backers. One reason for this is that the field of candidates is so big that investors are still hedging their bets, giving to Joe Biden, Kamala Harris, Cory Booker, and others. Yet none of the candidates has publicly visited any of the tech behemoths in person, unlike in previous election cycles, when a Google stop was part of the campaign circuit for aspirants aiming to prove their savvy.

The general cooling has shown up in more conspicuous places as well. Whereas tech giants co-sponsored many primary debates in recent election cycles — Facebook hosted two Democratic and two Republican debates in the 2016 race, while Twitter and YouTube each sponsored a Democratic one — this spring the companies made it clear to the debates’ organizers that they would no longer participate. Onstage at the first debate in June, Booker was pushed to name specific companies when discussing the dangers of corporate consolidation, and he responded with a juxtaposition that would have been unthinkable a few years earlier. “I will single out companies like Halliburton or Amazon that pay nothing in taxes,” Booker said. No one batted an eye at the comparison of Amazon (which had hosted a big presidential address from Obama in his second term) to Dick Cheney’s old company, and the moderators moved on.

Tech’s battered image goes only so far in explaining the Democratic Party’s retreat. Tech overreach may have been just as important — Silicon Valley billionaires’ being unwilling or unable to play nice with political veterans and what the tech crowd saw as their old, fusty rules when they did choose to get involved.

LinkedIn co-founder Reid Hoffman, for one, let the Democratic Establishment know he meant to innovate them into the future over the weekend of Trump’s inauguration. Hoffman — who’d advised Obama and Clinton, then finished Election Night 2016 by watching The West Wing’s pilot — stood alongside Zynga founder Mark Pincus at a secluded gathering of party donors in southern Florida and pitched them on a platform that would empower voters to pick issues to pressure Congress about. That project was greeted with groans when shared more widely, like many “disruptive” initiatives brought to Democrats in the aftermath of that humbling election. “It’s hubris that these folks believe they can do anything and everything better than anyone else and that if you just give them some time and money they’ll be able to fix it,” one senior party leader told me.

This dynamic was well illustrated by WeWork co-founder Adam Neumann, who’d never demonstrated much interest in domestic politics before. (Hoffman, at least, has been a big Democratic supporter for years.) The Israeli-born businessman, who in the past few weeks has reportedly decided to cut the valuation of his company precipitously in advance of an IPO, recently talked with a political pro about the feasibility of changing the laws so people not born in the U.S. could run for president. He was told that this would be quite an undertaking and that it was unrealistic—it would require a change to the Constitution. Neumann was then asked if he might consider running for governor or mayor in New York. According to someone familiar with the conversation, he replied, “Once you’ve reached my level of success, only president will do.” (A person close to Neumann says he was kidding about the requirements for running for office and denied he said that line.)

Dustin Moskovitz, perhaps the least-known Facebook co-founder, rose from obscurity in late 2016 to become the Democrats’ newest megadonor, one multimillion-dollar check for liberal groups at a time. Others, such as Hoffman’s LinkedIn co-founder Allen Blue, launched groups like DigiDems, promising to help the party’s political-technology efforts. It looked at first like a new era for Democrats’ relationships with their Silicon Valley backers, and the party’s central infrastructure responded in kind: The DNC began its internal data overhaul by hiring Raffi Krikorian, an Uber and Twitter engineering alum.

It took only months for cracks to show. In Krikorian’s first speech to DNC partners, in October 2017 in Las Vegas, the political novice sought to rouse the crowd by lauding the democratization of data and calling for access to the party’s voter files to be granted to all who consider themselves Democrats — not realizing this would endanger a major revenue stream for state Democratic Party organizations and potentially endanger incumbent lawmakers.

Meanwhile, Hoffman had partnered with a Democratic operative named Dmitri Mehlhorn and formed an all-purpose political shop called Investing in US, which sent Hoffman’s considerable money to a huge range of new initiatives, including widely heralded resistance-era groups like Run for Something and Indivisible. But in Virginia, the site of the group’s first major electoral investments, party officials who had originally been thrilled with Hoffman’s efforts and involvement began to chafe. They believed Mehlhorn was pressuring them to use political tools from Higher Ground Labs, one of the Investing in US beneficiaries. At the same time, he was funding an outside group, WinVirginia, rather than directly supporting local candidates in need of financial help. This group plowed money into conservative legislative districts even as Virginia’s Democratic leaders pleaded with it — unsuccessfully — to spend in more moderate areas they were already targeting. At one point, WinVirginia asked for access to the state party’s voter-data file only to be rejected by fed-up officials. Mehlhorn didn’t help matters in their eyes when he took what local pols saw as a victory lap that fall, claiming credit for Democrats’ widespread wins.

But by then, his reaction wasn’t much of a surprise to D.C. Democrats. When Mehlhorn arrived for a meeting with a Democratic super-PAC about potential collaborations on projects, including Alabama’s 2017 Senate race, things quickly went off the rails. Operatives there said they found him nervous to the point of paranoia when it came to security threats. As he spoke to them, at first he occasionally skipped words and wrote them down on a whiteboard instead, as if to avoid being recorded. Then, as the political team members explained their work to him, he asked how in-depth their message testing was. One of the operatives responded that it had matched the population segments they were targeting. “Okay,” said Mehlhorn. “Well, I think of the prehistoric megafauna.” The political veterans in the room were confused, so Mehlhorn continued. “White college women on campuses in Florida—they all voted for Trump because they have guns in their purses because they think black athletes are going to rape them.”

The operative froze, stunned. Mehlhorn appeared to be asking them to target racist white college women worried that Democrats would take their guns. The group’s leader cut in: “Dmitri, two things we will never do — foment hate against persecuted groups and send the wrong election date to people.”

“Okay, well, agree on the first; agree to disagree on the second,” Mehlhorn replied, according to multiple participants in the meeting. (Mehlhorn says this recounting of the exchange is “flatly misleading”: “One participant made a remark about GOP dirty tricks such as mailers and robocalls articulating false election dates. In response, I made an unfunny joke, and the room laughed—not because it was funny but because it wasn’t. None of us suggested or even considered that idea as one our side would undertake.”)

The conversation continued, pivoting to Alabama. But first Mehlhorn wanted to know if the super-PAC had a SCIF (a “sensitive compartmented information facility”) in the office. When told no but that there was another conference room if the current one wasn’t good enough, they moved to the second space. There, he had the political team unplug all the electronics in the room, including the TV monitor, and asked his hosts to put their phones in pouches to block surveillance. (He didn’t seem to notice the Apple Watches on his counterparts’ wrists.) He then pitched them on using billboards to advertise out-of-state events to white supremacists on Election Day and on boosting a conservative third-party candidate. He left the office with no collaboration agreement, though the New York Times later reported that a $100,000 Hoffman donation did go to a group experimenting with Russian-inspired social-media tactics meant to tank the candidacy of Republican Roy Moore. Hoffman apologized, saying he’d been unaware of the project, and promised to track his political investments more closely.

After the midterms, Mehlhorn’s team prepared a 15-page slide presentation outlining its work, a copy of which New York obtained. It is called “The Promethean Project,” and the slides detail the breadth of the group’s investments, listing 30 organizations it had funded or worked with, divided into categories like “New, Innovative Technology Tools,” “Changing the Culture of Voting and Increasing Turnout,” and “Fueling Resistance Energy: Candidates and Volunteers.” Among them are well-known and emerging partners like MoveOn and BlackPAC; some were helping redefine the modern Democratic Party in the Trump era, but others, like MotiveAI, got into trouble during the midterms for their unconventional work. (MotiveAI was found to be tied to Facebook groups including one page called “The Keg Bros” that both attacked Trump donor Rebekah Mercer and wrote that Representative Tulsi Gabbard “makes us want to go Democrat,” labeling her a “certified C.W.I.L.F.,” a sexist acronym for “congresswoman I’d like to …”) The presentation says the experiments “communicated with” over 20 million voters in 53 House districts during the midterms.

But the deck offers no mention of the Hoffman-funded initiative causing the most agita in some D.C. circles. Before news broke of the unseemly electoral experiments Hoffman had paid for in Alabama, the team began telling allies about a $35 million project they called Alloy, an attempt to build a voter-data venture outside the DNC run by three former Obama aides: Mikey Dickerson, Haley Van Dyck, and former U.S. chief technology officer Todd Park. At first, party officials feared the undertaking would interfere with their own centralized efforts to reinvent the Democrats’ data program. More than once, they sat down with Hoffman’s team members to make the case that building a parallel voter file would lead to a logistical and political nightmare for Democratic groups and candidates. By mid-2019, it sounded to Democratic officials as though the plan had shifted slightly — it would now be more of a data warehouse for party-affiliated groups — and as the year progressed, Mehlhorn met often with party officials to keep them posted. At times, said people who’ve met with his team, he expressed exasperation about their animus toward Hoffman, and when asked why his group wouldn’t just invest in the party’s existing centralized data program, he said this outside work was more efficient and allowed his team to avoid difficult party officials and campaigns.

Leaders of top Democratic groups mused privately about no longer taking Hoffman’s money, but conversations between the sides continued and hope of a data collaboration persists, particularly among those who readily acknowledge the success of some of the groups he has funded. On June 25, the DNC received just its third check this year for the legal maximum, $865,000. It was from Hoffman. Within a month, he sent over 40 state Democratic parties $10,000 each. And in August, Democratic operatives started hearing about Mehlhorn’s next plans. Among the projects: researching various voter groups, including “softer” white nationalists.

Facebook’s entry into Democratic politics was considerably more cautious but perhaps no more self-aware. Mark Zuckerberg had first tried engaging a bit with politics by funding FWD.us, an immigration group, starting in 2013, but it was Sheryl Sandberg, a Treasury Department alum, who had first pushed the company to build up its presence in Washington. No one ever thought Zuckerberg would do much lobbying; he was too busy and preferred to limit his few interactions to heads of state. But eventually he came to see the use of a positive relationship with the White House, since his and Sandberg’s primary political concern was executive-branch audits or oversight. They maintained a solid working relationship with Obama, and Sandberg courted Hillary Clinton’s inner circle. Throughout 2016, Sandberg had the ears of both Clinton and her top aides, advising them on everything from tech policy to the candidate’s image.

Election Night upended this strategy, not only because of Facebook’s scant ties to Trump but also because its leaders suddenly found themselves in the middle of a historic political hurricane. Rattled, Zuckerberg insisted two days after the election that it was “a pretty crazy idea” that fake news shared on the platform had “influenced the election in any way.” But Obama, still the president, was watching from Washington, and he told his staff to make time for him to speak with Zuckerberg when they were both in Lima for a conference a week later. In Peru, Obama looked Zuckerberg in the eyes and told him, “It’s not crazy,” insisting the CEO treat fake news, disinformation, and Russia seriously. Taken aback, Zuckerberg insisted it was a complex problem but not a particularly widespread one.

Back in California, Zuckerberg stewed. He was shaken, questioning his once-strong relationship with the powerful and well-liked Obama but refusing to admit fault. One month into Trump’s presidency, he published a manifesto about Facebook’s role in the world that included nothing about election interference — probably the bare minimum many Democrats would have required to continue counting Facebook as an ally. By then, people close to Zuckerberg and Sandberg were convinced the pair were obsessed with not antagonizing Republicans in and around the new White House.

It had been taken as gospel in certain Facebook circles that Sandberg would’ve been in Clinton’s Cabinet, but by late 2017, she was facing considerable resistance from even her closest allies in Democratic politics. Shortly after Minnesota senator Amy Klobuchar announced she’d be introducing legislation to make online advertising more transparent, for example, Sandberg called her. On that call, Sandberg asked that “issue ads,” as opposed to political-campaign ads, not be included and that Facebook found that nonnegotiable. Klobuchar, however, sternly told her that excluding issue ads would leave an unacceptable gap in the policy, making it a nonstarter. Facebook ultimately caved. The tide turned decisively against Sandberg early the next year when the Times revealed she’d asked staff to investigate George Soros after he made negative comments about Facebook. No rebuke was more stinging, though, than an indirect one from Michelle Obama: “It’s not always enough to lean in,” the former First Lady said in Brooklyn last December. “Because that shit doesn’t work all the time.”

For years, one of Zuckerberg’s informal rules was that Capitol Hill testimony was beneath him, so when he arrived in Washington to speak with lawmakers in April 2018 and called social-media regulation “inevitable,” those close to him viewed it as a significant double concession. Facebook leaders and their allies classified Zuckerberg’s two days in the spotlight as successful, largely thanks to older senators’ out-of-touch questions on day one, which — they felt — made Washington look behind the times and thus made Zuckerberg and Facebook appear sleek.

Even so, Zuckerberg couldn’t tolerate the hostility. During the first break in questioning on his second day of testimony in D.C., he sidled up to the House Energy and Commerce Committee’s then-chairman, Oregon Republican Greg Walden. He was surprised by how harsh the committee’s Democrats were being toward him, he told Walden. Zuckerberg had expected the Democrats to be relatively friendly, but now he was objecting to the opening remarks from New Jersey’s Frank Pallone, the committee’s top Democrat, who called Facebook “just the latest in a never-ending string of companies that vacuum up our data but fail to keep it safe” and made the case for stricter regulation. Zuckerberg’s admission was a remarkable one to make so casually to any lawmaker, let alone a Republican, and Zuckerberg didn’t share his concern with any of the committee’s 24 Democrats.

In the ensuing months, Facebook’s leaders thought they were smoothing relationships with the left by acknowledging some of their structural problems. A few weeks after Zuckerberg’s testimony, the company hired an ACLU veteran to audit the harm it had caused minorities, including by letting advertisers find ways to target users by race. However, Democrats believed the company was doing too much to appease conservatives, too: Facebook had simultaneously tapped former Republican Arizona senator Jon Kyl to review accusations of internal anti-conservative biases. Then, in September, Facebook’s top D.C. official, Joel Kaplan, a George W. Bush White House alum, was spotted at the Senate hearings for his friend Brett Kavanaugh — who’d been guided through the Supreme Court nomination process by Kyl, who then, in turn, voted for Kavanaugh upon returning to the Senate temporarily after John McCain’s death. This March, a Washington Post op-ed from Zuckerberg proposing potential regulation guidelines was greeted with eye rolls from some Capitol Hill Democrats, and in April Oregon senator Ron Wyden tried persuading regulators to make Zuckerberg personally liable for Facebook’s privacy violations.

Things reached a breaking point in late May, when Trump allies started sharing a distorted video of Nancy Pelosi and Facebook refused to take it down. Pelosi had been souring on Facebook for months, telling journalist Kara Swisher in April about her “questioning attitude” toward the company. No one from Facebook had called her to discuss those comments, and as fury now mounted in her caucus that the company wouldn’t budge on the video — and therefore continued to make money from it — Pelosi grew livid. Recognizing the peril of ending up on the House Speaker’s bad side, Zuckerberg — who has two ex–Pelosi aides on Facebook’s lobbying team — called her office to discuss the clip and disinformation more broadly. But Pelosi, fed up with him, didn’t pick up and refused to call back. In June, the House Judiciary Committee opened a probe into tech giants’ anti-competitive behavior, and Congresswoman Anna Eshoo, a close Pelosi ally who represents much of Silicon Valley, invited Roger McNamee, an early Zuckerberg adviser who has become one of his fiercest critics, to address interested lawmakers. About 30 House Democrats showed up to the dinner, which lasted around two and a half hours. “I’m not sure they yet recognize the gravity of [what’s happening],” says David Cicilline, the Rhode Island congressman who leads the House’s antitrust subcommittee. “The conduct of Facebook and the leadership of that company has been one of repeat offenders.”

Again and again, Washington Democrats were shocked that the company could be so blind to its own faults and so uninterested in doing penance. Weeks after the Pelosi-video debacle, Facebook representatives trekked back up Capitol Hill to explain the company’s new cryptocurrency plan, apparently unprepared, in Democrats’ eyes, for the skepticism they’d encounter. “Facebook is dangerous,” said Ohio senator Sherrod Brown to the Facebook official overseeing the project. “Now, Facebook might not intend to be dangerous, but surely they don’t respect the power of the technologies they’re playing with. Like a toddler who has gotten his hands on a book of matches, Facebook has burned down the house over and over and called every arson a learning experience … Facebook has demonstrated through scandal after scandal that it doesn’t deserve our trust. It should be treated like the profit-seeking corporation it is, just like any other company.”

Facebook, of course, isn’t just any other company, and Silicon Valley isn’t just any other industry. But the more leading Democratic senators treat them as such, the more Big Tech’s evolving role in politics seems poised to follow Wall Street’s from just a few years earlier — perhaps even with Silicon Valley’s leaders complaining all the while about having been forced to second-guess their support of Democrats. After all, even an Establishment Democrat like Joe Biden, devoted above all else to the principle of cooperation, has started looking askance at Big Tech. Shortly before Pelosi stopped taking Zuckerberg’s calls, Biden said breaking up Facebook is “something we should take a really hard look at.”

This spring, when Warren announced her proposal to break up companies like Facebook, an employee asked Zuckerberg about it: Was he concerned? There was already reason to believe Facebook was monitoring Warren closely — it had taken down her ads calling for its dissolution but restored them when people noticed, claiming the ads had violated company policy for depicting its logo.

I run Facebook, and she’s a presidential candidate calling to break Facebook up, Zuckerberg said onstage. Of course I’m concerned. But it hadn’t occurred to him that it might, at some point, have been worth at least trying to give Warren a call. She certainly wasn’t likely to call him anytime soon.

*This article appears in the September 16, 2019, issue of New York Magazine. Subscribe Now!