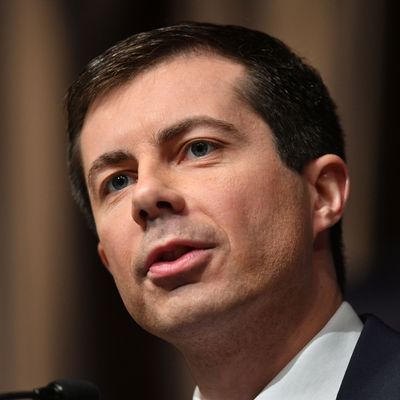

Mayor Pete Buttigieg is not your average presidential candidate. Currently 37, if nominated, he would become the second youngest major-party candidate in U.S. history (William Jennings Bryan was 36 in 1896); if elected he’d be the youngest president by a wide margin. Despite his youth, he’s that increasingly rare commodity: a military veteran. He’s the first openly gay Democratic presidential candidate. He has an unconventional résumé as the mayor of a relatively small city (South Bend, Indiana, population: 102,245). He harkens back to an abandoned tradition of multilingual aspirants to the presidency, as his campaign confirms his working knowledge of eight languages (English, Norwegian, Spanish, French, Italian, Maltese, Arabic, and Dari). That would put him in the same company as Thomas Jefferson, who was fluent in English, French, Greek, Italian, Latin, and Spanish, and knew some Dutch and Arabic (!) as well.

But Buttigieg stands out in an even less conventional way: He’s an observantly religious (Episcopalian) Democratic millennial, part of a party and a generation increasingly characterized by nonsectarian belief or unbelief, and prone to thinking of religious expression in a political contest as something those intolerant, Bible-thumping conservative Republicans do. That makes him an unusually effective scourge for politicized conservative Evangelicals who can’t begin to grasp the phenomenon of a married gay Christian who may go to church more often than they do. But if he’s not careful, he could alienate both irreligious voters and those whose view of the intersection of faith and politics don’t match his own. It’s inherently a balancing act.

Mayor Pete shows his understanding of this problem in answering a very basic question from Religious News Service’s Jack Jenkins about “the appropriate role of religion in American politics”:

You should be able to offer (messages) that anyone — of all religions or of no religion — should find meaningful. Sometimes we’ve been afraid to use this language because we think it means not honoring the separation of church and state. For me, it means we need to honor the separation and also speak to those who are guided (by faith.)

This is a very carefully wrought answer that avoids the sort of shrugging my religion is an accident of birth language that was common in a bygone era when everyone was nominally religious, and the off-putting militancy of those who would build a Christian Left to fight the Christian Right for control of the Bible and the cross. Asked if he thought conservative Christians were “sinful” for their love of Donald Trump, Buttigieg stuck to criticizing the hypocrisy involved in that unnatural attachment:

I’ll be careful to use that word to kind of point out a speck in my brother’s eye. What I would say is that it’s clear that some naked sins are being at best condoned by people who then summon religious arguments. That rings more and more hollow. It’s not just that we might have a different interpretation of faith, it’s that these arguments no longer stack up even on their own merits, right?

For example: Mike Pence’s view of Christian sexuality is obviously a little different than mine. But even with his view, it makes no sense to condone this president and his behavior. So there’s two layers to this. There’s the fact that I subscribe to a vision of faith that leads me to a certain place politically. But it’s also just seeing the hypocrisy among people who now endorse people and practices that are offensive, not only to my values, but to their own.

The fine line Mayor Pete has to walk is one that isn’t necessarily very politically convenient. Asked about his silent attendance of a recent protest near the White House held by the Poor People’s Campaign (much of whose leadership, notably Rev. William Barber II, is very definitely faith-based), Buttigieg is particularly circumspect:

What I saw was a moral call coming from people of many very different faith traditions, all concerned about how policies of this White House were harming those most in need of our support. And, to me, there’s a direct line between that moral call and what is in the Christian faith. But the people who were there were not all Christian. Nobody was there as a Democrat or a Republican, which is one of the reasons why I understood that my role was simply to be there and witness.

You have to acknowledge that Pete Buttigieg’s single biggest political problem as a presidential candidate is his lack of demonstrated appeal to minority voters, and especially African-American ones. Tensions back home in South Bend over police misconduct toward black citizens have made this problem even more acute. Being conspicuously identified with someone like Barber (often considered the heir to Martin Luther King’s legacy of church-based social protest) would be worth its weight in gold to a white wine-track candidate like Mayor Pete. But Buttigieg takes his own religion seriously enough to avoid opportunistic use of it even when he really needs it. That won’t help him become the 2020 Democratic presidential nominee. But perhaps he is storing up treasure in heaven.