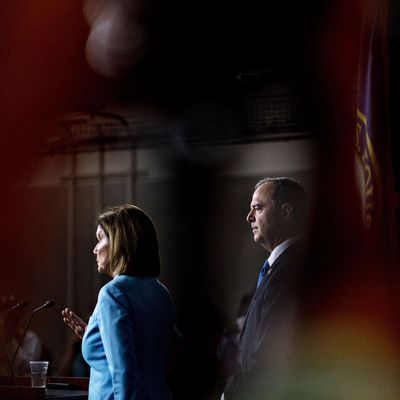

When House Speaker Nancy Pelosi publicly announced an impeachment inquiry on September 24, she made it clear that the trigger for her decision, and her primary focus, was the president’s efforts to coerce Ukraine into a damaging investigation of Joe and Hunter Biden. As part of that focus, she put the principal investigation into the hands of Intelligence Committee chairman Adam Schiff instead of the traditional impeachment forum of the Judiciary Committee. But at the same time, she did not foreclose the possibility of additional articles of impeachment; even before her public announcement, she asked the chairs of all the committees investigating Trump to prepare to “send Nadler their best cases for impeachment,” as my colleague Gabriel Debenedetti reported. The idea was that the Judiciary would draft the formal article or articles of impeachment, even if the charge the House chose to pursue was a simple matter of a Ukraine quid pro quo aimed at Joe Biden.

At that time, understandably, the many House Democrats (and their even more numerous progressive allies in the opinion biz) who had been fruitlessly agitating for the impeachment of Trump before the Ukraine story came out were upset about the idea of a narrow impeachment inquiry. What about the Mueller Report? What about the obstruction of justice evidence Mueller invited Congress to use in an impeachment proceeding? Would a narrow focus on Ukraine implicitly exonerate Trump on matters not related to that incident, or encourage him to do bad things in the future? And given the extremely high odds that the Senate would refuse to remove Trump from office on narrow or multiple articles, should Democrats throw everything they have at Trump to damage his 2020 reelection prospects?

These were all very good questions, but Pelosi seemed clearly to believe that the answer to the last one was, No, go with something simple the public can understand. And the rapidly rising public support for impeachment of Trump after Pelosi’s announcement seemed to vindicate her strategy.

But Trump himself is now complicating the strategic calculation, just as he did by beginning his campaign to get Ukraine to destroy Biden even as Democrats were still debating what to do with Mueller’s report flowing from Trump’s behavior toward Russia. The man just won’t stop committing impeachable offenses. And worse yet, his most egregious impeachable offenses are aimed at frustrating the Ukraine investigation, and Schiff is among many Democrats pointing this out, as the Washington Post reported last week:

The impeachment inquiry is having a hard time getting central players to even talk, and on Tuesday, the White House said it wouldn’t cooperate with the impeachment inquiry in any way.

Democrats are saying all this amounts to obstruction and are hinting strongly at what the House can do to get around this: impeach Trump for blocking the investigation.

“The failure to produce this witness [diplomat Gordon Sondland], the failure to produce these documents, we consider yet additionally strong evidence of obstruction of the constitutional functions of Congress, a coequal branch of government,” said House Intelligence Committee Chairman Adam B. Schiff (D-Calif.), who has become the face of the investigation, on Tuesday.

Obstructing a congressional investigation of the Executive branch, particularly if it involves potentially impeachable offenses, is a well-acknowledged impeachable offense in itself, as my colleague Jonathan Chait observed in making “obstruction of Congress” a whole category in his menu of “high crimes and misdemeanors” Trump has committed:

The Executive branch and Congress are co-equal, each intended to guard against usurpation of authority by the other. Trump has refused to acknowledge any legitimate oversight function of Congress, insisting that because Congress has political motivations, it is disqualified from it. His actions and rationale strike at the Constitution’s design of using the political ambitions of the elected branches to check one another.

This is hardly a novel concept. One of the three articles of impeachment the House Judiciary Committee approved in 1974, which triggered Richard Nixon’s resignation, involved similar but arguably less comprehensive efforts by the Tricky One to obstruct Congress:

[Nixon] failed without lawful cause or excuse to produce papers and things as directed by duly authorized subpoenas issued by the Committee on the Judiciary of the House of Representatives on April 11, 1974, May 15, 1974, May 30, 1974, and June 24, 1974, and willfully disobeyed such subpoenas. The subpoenaed papers and things were deemed necessary by the Committee in order to resolve by direct evidence fundamental, factual questions relating to Presidential direction, knowledge or approval of actions demonstrated by other evidence to be substantial grounds for impeachment of the President. In refusing to produce these papers and things Richard M. Nixon, substituting his judgment as to what materials were necessary for the inquiry, interposed the powers of the Presidency against the lawful subpoenas of the House of Representatives, thereby assuming to himself functions and judgments necessary to the exercise of the sole power of impeachment vested by the Constitution in the House of Representatives.

Nixon, moreover, didn’t try to incite violence against his congressional tormentors as Trump has repeatedly done.

You could certainly make the case that an article of impeachment involving “obstruction of Congress” with respect to the Ukraine scandal is a natural sidebar to an article on the scandal itself, in that it strengthens public perceptions that far worse presidential behavior probably occurred but cannot be documented. But there are bigger questions about public perceptions. Yes, it’s clear under the Constitution and any reasonable interpretation of the Founders’ intent that “high crimes and misdemeanors” do not require violation of criminal statutes. Indeed, the kind of misconduct that cannot be addressed by the criminal-justice system is precisely the sort of thing the Founders had in mind in providing for impeachment. But does the public understand that, and if so, does it accept it? The Ukraine scandal clearly involves conduct most people would consider criminal (particularly if it’s explained as a violation of campaign-finance laws, including those aimed at preventing foreigners from being involved in U.S. elections). Obstructing Congress? Maybe not so much, particularly since Congress’s job approval ratings are significantly worse than Trump’s (21 percent, according to the latest RealClearPolitics polling average).

While what to do with Trump’s obstruction of Congress is one question House Democrats must face before pursuing a Ukraine-only impeachment strategy, it’s not the only one. Other examples of impeachable conduct keep popping up, as the Washington Post observed over the weekend:

Within a one-day span, The Washington Post reported that Trump sought to enlist then-Secretary of State Rex Tillerson in the fall of 2017 to stop the prosecution of a Turkish Iranian gold trader represented by Rudolph W. Giuliani. The former New York mayor is Trump’s personal attorney.

The Financial Times reported that Michael Pillsbury, one of Trump’s China advisers, said he had received potentially negative information on Hunter Biden during a visit to Beijing.

What do you do when the target of (to use the criminal-justice analogy) a prosecution won’t stop doing crimes for long enough to pin down an indictment?

“We’re basically getting like three new impeachable offenses a day, so it suggests that we are only seeing the tip of the iceberg on what’s happening,” said Daniel Pfeiffer, a former Obama strategist who hosts “Pod Save America” and who has been pushing Democrats to expand their probes.

Toss in the unacted-upon Mueller findings, and whatever fresh hell may come up from past, present, and future Trumpian misconduct, and you can see that when the deal finally goes down, House Democrats will have a tough decision to make, whatever Pelosi originally intended. And it’s a big question for Republicans as well, who may get a tad reluctant to go to the mat for their president without knowing what other nightmares are in undisclosed closets — or have yet to be fully formed in Trump’s own twisted imagination.