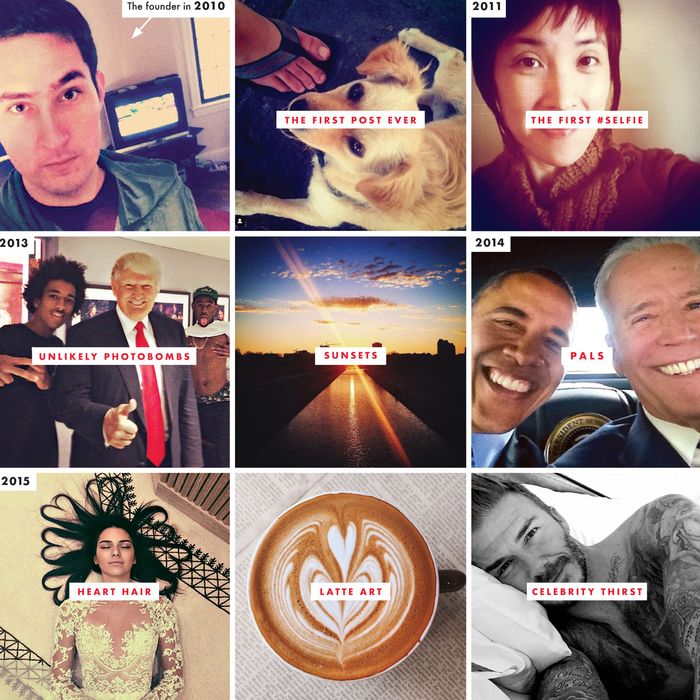

As the decade began, there were reasons to be optimistic: America had elected its first black president, and despite a global recession just two years earlier, the world hadn’t cascaded into total financial collapse. Obamacare, for all its flaws, was passed, and then came the Iran deal and the Paris climate accords. Sure, there were danger signs: the anger of the tea party, the slow hollowing out of legacy news media, a troubling sense that somehow the bankers got away with it. But then maybe the immediacy of social media gave some hope, at least if you listened to the chatter of the bright young kids in the Bay Area trying to build a new kind of unmediated citizenship. Maybe everyday celebrity, post-gatekeeper, would change the world for the better. Some of that happened. But we also ended up with the alt-right and Donald Trump, inequality, impeachment, and debilitating FOMO. How did we get here? Throughout this week, we will be publishing long talks with six people who helped shape the decade — and were shaped by it — to hear what they’ve learned. Read them all here.

The man who unleashed Instagram on the world stands six-foot-five-inches tall and has the careful demeanor of someone who knows people are listening closely to what he’s saying. Talking to him, one gets the sense that he’s a step ahead — that for him, conversation is a game and he’s mapping out potential outcomes. That’s why, for example, he won’t be baited into reckless proclamations about impending class wars or Mark Zuckerberg’s complicated relationship to politics. At the same time, he possesses the excited curiosity of a kid discovering the solar system. This is a man who co-founded a company at 26 that made him a billionaire by the time he was 32 (today he’s 35). Even after a decade that has left many people confused by the role of social media in our lives, Kevin Systrom holds fast to the original premises of Silicon Valley: Technology can improve our lives, connecting people helps humanity, and tech guys aren’t just in it for the money.

What does it feel like to have changed the world with Instagram and to see the world changed to be part of Instagram?

It’s really strange to me to walk down the street and see people using a product that I remember very clearly making, but what’s weirder is it doesn’t actually wow me. When we launched, I think it was 24 hours later, there was someone using it on the subway on the way home. I was blown away. But we didn’t set out to change the world; we just set out to make a good product that we wanted to build and we wanted to use. We got fairly lucky in that, it turns out, what we wanted, a lot of other people wanted. That’s not lost on me, but it is kind of lost on me.

One really concrete example of how it changed culture is that I just went to a music show a couple of weeks ago and they confiscated our phones.

Yeah, I went to a comedy show once, where they put them in these secret bags.

There’s a club I like to go to, and they literally said you cannot use Instagram in this club. The owner said, “It’s really, really disruptive to the experience of being here.” Do people ever complain to you?

All the time. But they just want a verified badge. They don’t complain about the product, no.

Really? No one ever says to you —

You’re mentioning people retracting from Instagram in some way. I see that as kind of like hip coffee shops that ban Wi-Fi because they want more conversation. I get it. But it also is the other way. You walk into any museum today: Ten years ago, they banned photography; now they’re like, “No, take photos of yourself with the art. It’s great publicity.” So you see organizations that go the opposite way, like fashion shows. Now it’s literally designed to be an Instagrammable event. There are restaurants whose dishes are effectively plated to be Instagrammed.

I used to go on a lot of hikes and not record or share them. I’d simply have the experience. Do you think there’s any aspect of us now that goes on the hike just to share the experience, as opposed to just having the experience?

I’m sure some people do. When I’m on my bike, I go across the Golden Gate Bridge and it’s full of people taking selfies. And I’m sure that drives them to want to go, because they have to show people they visited San Francisco. But I think broadly, you’re having an experience, and the joy of that experience you want to go share with people you love. And I think that’s great. That’s why we created the platform. My job at Instagram was to create products that people loved and found useful, and obviously take into account what the side effects are of building this thing. But often I think people like to judge products based on a small, interesting, and potentially volatile use case, rather than on how most people use it. Broadly, people use Instagram to share with their family and their friends and see what exists in the world that might be interesting to them. And that was always the goal.

I was in Paris and there’s one particular pastry that looks like it was designed for Instagram. Could you have anticipated that?

Not at all. If you look at our first photos in our feed meeting, me and my co-founder, they’re of half-eaten sandwiches and cups of coffee. But I do distinctly remember, when we were deciding what to do, I had this moment where I really felt clarity, that the fact that phones now had cameras meant there was going to be this massive shift in how people shared their lives. The idea that you could immediately show someone what you’re doing, that’s going to happen. I guess, if I were even smarter, to think of the next chapter, I might see the repercussions in a restaurant or a club. But instead, I got a front-row seat to watch that transformation happen. You saw organizations that didn’t necessarily embrace technology in the past start to embrace technology. I remember signing the pope up for Instagram and thinking, Wow. At the highest abstract level, what a magical thing that that can happen, period. A couple guys can create something and, in a few years, shift the world in some meaningful way for an organization that’s been around forever.

Did you personally sign him up?

Yeah. I went to Vatican City twice. The first time was to present the idea.

I explained why, no matter who you are, if you have something to say, Instagram’s the place to do it. He said, “Well, my team will look at this and give me their decision. But they’re not in charge, because everyone has a boss.” He pointed at himself. He said, “Even I have a boss,” and he pointed up in the sky. I thought that was really funny. A few weeks went by, and they decided collectively — he decided they were going to sign up. They called back, and they said, “Can you come back to sign him up?” I was like, “Well, you just fill out a form. It’s really easy. You just click.” My COO came over and elbowed me in the shoulder and was like, “You get yourself to Rome.” We went two days later. We showed up, and he was finishing Mass. We had just flown in. We were bleary-eyed. He walked in, and he turned the corner, and he goes, “Kevin!” It was like seeing an old friend from your basketball team or something. It was such a fun moment for me, just his humility and friendliness throughout the whole process was pretty awesome. We had an iPad, and it was all set up. The name was filled out. So, literally, all he had to do was click sign up.

When did you first start thinking about selling Instagram? Or selling it to Facebook?

For a while, we were pretty steadfast that we were going to be independent.

In fact, we raised a venture round maybe two days before we sold the company. It was a last-minute thing that we had to consider, where all of a sudden we had raised this venture round, and then Mark came in and effectively doubled the valuation and pitched a really compelling version of the future where we could work together on creating this thing, but it would stay independent and we would get to build it. The goal was not to sell the thing. We had tons of interest from folks along the way, and we just said, “No, thank you.” And basically Facebook just came in at the right moment. Really, we saw it as a way of accelerating the success of Instagram. They definitely helped along the way.

The idea of scaling has exploded in the past decade — even just the transformation of what you sold Instagram for, $1 billion, versus what it’s worth now, $100 billion. How do you even wrap your mind around that growth?

We’ve entered a world where there’s basically zero marginal cost to expand.

In the past, if you wanted to sell another car, you had to build another car.

It took a long time. It took an enormous amount of money. Then that car went out, and maybe you sold it, maybe you didn’t. Whereas Instagram’s kind of like — imagine you build an imaginary car. If it’s a good imaginary car, all of a sudden a billion people are using it. If you’re digital, it’s no longer hard to expand your business. The reason we’re in this moment is because there’s no capital cost to expansion.

You say there are zero costs, but nothing is zero cost, literally. There are, potentially, human costs or hidden costs. I think you, as a confident, well-adjusted guy —

I appreciate that I fooled you.

I think I’ve listened to enough interviews with you that I can say you seem like a pretty healthy, well-adjusted guy. Did you anticipate the kind of insecurity or the social-emotional impact on the audience for these pictures, for instance?

The people I have met and talked to, they typically express the pressure to feel like they have to put on the idea that they’re living this perfect life, that they go out every night, that they spend a ton of money, that they’re with fancy people, that they’re skinny, the list goes on. I’d say that most of the pressure is thinking, What part of my life can I share? Am I cool enough? Are my friends doing something without me? At the beginning, this was a community of photographers and designers. The idea was more that you had these creatives, and you gave them a fun, creative tool. Very quickly, it morphed as more people used it for just showing your life on the go. The one decision that I think made this a potential issue was that it was public by default, so it meant that if you were willing to share your life, people would follow. Then, the more interesting life you have, the more jealous others might become. It diverged.

While you were watching that happen, what were you thinking?

Initially, the idea was how do you maximize the number of people that use it? Facebook created that science. We adopted it, and it worked really well.

The inflection point happened when we started ranking feed. Because all of a sudden, it wasn’t just who posted and when. When we started ranking feed, in 2016, a lot of people complained, but it’s very clear: People with ranked feed use it a lot more. People without ranked feed use it less. We got really, really good at ranking feed. Usage went through the roof. That was an inflection in our growth.

So you saw this as a good thing?

No. No, no. I don’t know how to explain this, but in business, winning is always great, but winning always comes at some cost of some other part of the business. All of a sudden, a normal user might feel like, Maybe I shouldn’t post as much. Maybe I should just look at Beyoncé. Or, If I’m going to post, it better be good. That wasn’t great, because we were built upon the fabric of people sharing their daily lives. I went through Instagram yesterday, and I was scrolling through my feed; I think I probably looked at, I don’t know, 40 or 50 posts, trying to find a single one of any of my friends. It was all brands. That’s a transition that happened with Instagram. It became a marketing tool for a lot of people, because we had this critical mass.

That change — the invention of this whole influencer economy and creating businesses within your platform — came from the users, and their innovations often seemed to outpace the app’s capabilities. How did you negotiate that?

At the beginning, when we were small, there were no influencers. I think once we crossed say, I don’t know, 100 million people, it became clear that you could maybe start to have an interesting business if you were just on Instagram. But it wasn’t until we were, say, 600 or 700 million using that app that I really started to notice it. And I think the first context where it was raised was just around advertising, because all these influencers were going direct to these brands, and these brands were confused because they didn’t know how the advertising performance compared to our native advertising. That was one of the questions we had to deal with as we grew.

Do you think when a platform becomes overly dominated with brands, it’s the kiss of death?

Clearly not, because Instagram is doing very well. But I felt the need, as the leader and the founder, to get us back to a place where we would protect that family-and-friends sharing. So we took that feed ranking and we prioritized friends and family. That kept people on the platform. But still, there was this headwind of what’s happening to the normal folks. The way we found our way around that was we introduced Stories. It created this outlet where people could share their lives on the go but not feel the need to have it look perfect on a profile. They could limit the audience. They could be goofy if they wanted to.

I use it approximately 25 times a day. I love it very much.

Oh, I remember I was hand-wringing. When we were about to launch, the consensus inside of Instagram-Facebook was not that this thing was going to work. But then we launched it, and all of a sudden, we saw this torrent of content production. My point: You can crush your company under the weight of success. But anyway, backing up, I think a lot about the social effects. I think a lot about what it does in peoples’ lives. Also, you said well adjusted. I want to counter, which is that —

Really?

No, no. In high school, I was the tall, nerdy guy who liked computer science and electronic music, by the way, when electronic music was not cool.

David Guetta wasn’t headlining —

Yeah, you had a radio station out of your —

Yeah, totally. Dorm room. But my point is, I was not the cool kid.

But you seem like you have a healthy relationship, let’s say, to imagery and the world. Have you seen the movie Ingrid Goes West, for example?

I haven’t, no.

It’s an Aubrey Plaza movie in which an Instagram obsessive stalks an influencer. It’s a very dark movie.

That sounds dark, yeah.

It’s an extreme study of the female psychology of hero worship. I think, for a lot of women, the emotions and experiences of flipping through a magazine, with fitness ideals and beauty standards and all of that, have been translated to Instagram.

Well, I think one of the biggest challenges of social media is that you need to work really hard to make sure you don’t put on your hat as you but as the user when you’re building the project. We did enormous amounts of focus groups with teens; understanding how they use the product, understanding what they liked, what they didn’t like. But I don’t have a teen in my household.

But you do now have a child?

A 2-year-old who doesn’t use social media.

Will you let her use social media?

Of course.

At what age, do you think?

Whatever the legal age is, which, right now, is 13 in the United States.

Most kids have it much younger than that.

That is not a fact I can substantiate.

Okay, I’ll just say, anecdotally, most of the parents I know generally seem to give their kids phones around 9, 10, 11. Social media around 11, 12.

See, I’m not in these parent circles. Most of the kids that I meet, at least in Silicon Valley, maybe because their parents work at these companies, they know the age is 13.

Do you think you’ll monitor her Instagram account?

Of course. I’m going to be a normal parent. But also, if Instagram’s around 12 years from now, that’s awesome. So I’m going to be very happy if I’m going to have a conversation with my daughter about Instagram.

My daughter’s already moved on to TikTok. She’s 14. But I’m still wary of how she performs her life online. What will you say to your daughter? What if she starts doing inappropriate things or things you’re unhappy about?

It’s really hard for me to answer the hypothetical, potentially 12 years from now. I don’t know. Let me get there. But I don’t actually espouse any crazy, contrarian views on social media different than any other parent. I’d worry about my kid’s safety. I’d worry about her well-being. I’d worry about her confidence.

Do you remember the first time law enforcement had to get involved in Instagram?

I do. I can’t share details of what it was about, but I got an email from a very official-sounding federal department and they needed information about specific accounts because it was involved in some very large thing. So I had to figure out what to do about it. This was pre-Facebook. A year or two later, we had a law-enforcement team that fielded these requests, vetted them, made sure that they were legal, etc. But I do remember that moment because I was the one who got the email.

I’ve heard you say you were very proactive in the beginning about kicking people off who were trolling.

Yeah, we weren’t the first social-media product to hit the block. I had worked at Odeo, which became Twitter, so I was very familiar with their journey. Anyone can create a photo-sharing app; not everyone can create a community. If you can protect that asset — if you can help nurture and grow it — and your product doesn’t suck, you have created something much more valuable than a great product with a terrible community. Our first value at Instagram was always community first. It got changed, by the way, when we left.

What is it now?

I don’t know, but it was removed.

Some of those policing decisions fostered a feeling of conspiracy. A lot of people think, Oh, my posts are being hidden. Or, I’m not being shown, because I’m inappropriate, or, I’m saying something political, or, There’s a nipple in my post.

I think I understand what was happening. I don’t have proof, but there were lots of systems where, yes, if there was clearly nudity, it would get flagged by the community. It would be reviewed by a human and then taken down. There was some automatic stuff happening if it was very clear. There were a lot of bugs in the system in terms of ranking. I remember posting with some hashtags, and they wouldn’t show up on the hashtag pages. I was like, “Team, what’s going on?” After a day of debugging, they realized the spam filter had accidentally labeled me spam because of, I don’t know, it might have been something like I put a URL in my bio. Anyway, there was a mistake. I think what happens at scale, you don’t really see the edge cases. Then it leads to people thinking they’re getting shadow banned and it’s a bug in the software. I’m pretty confident those were most of the issues.

Why ban nudity?

Apple’s very clear. If you have nudity in your app, you’re not allowed in the App Store, but I think we probably also would have decided to have similar standards, even if it wasn’t in the App Store.

Is there something important about keeping nudity out? Is it that it cuts out that whole porn sector?

Yeah, if your 14-year-old’s going to Instagram and parents are saying, “Wow, there’s a lot of porn on Instagram,” you’re not going to be comfortable, right?

But there is porn on Instagram.

There might be, but saying there’s a lot is a very different thing.

It’s been interesting to watch my teens show me things happening on Instagram that very much reflect the real world but have become weirdly virtualized, like drug dealing or invitations to secret parties or things that high-schoolers have always done. Instagram has begun to reflect the negative sides of the real world.

You could have all the same conversations about the internet. I think the difference is we tried very hard to make a lot of this stuff not happen. I think had we not, it would be in a much worse state today. But that doesn’t mean there’s nothing. It’s a constant fight.

The narrative around Silicon Valley in the media has changed in the past decade from the default “They’re saving the world” to a more cynical view of how it’s all working. Have you felt that change?

I don’t know that it’s changed. I just think people have come to realize what is true. There was a while where everyone thought it was all about solving the world’s problems and it was all mission driven. There is a lot of that, but the idea that there’s no sense of capitalism, no sense of winning at all costs, would be misguided. People have come to realize that Silicon Valley is just like every other large center of business in the world. It’s an industry, and it has its cast of characters. It’s not all philanthropy.

Do you think the media gets anything wrong about Big Tech?

That’s a really hard question. Obviously, analysis of any industry, if you’re not literally in that industry, leaves itself open to some misinterpretation. But I don’t think it is broadly misinterpreted. Sometimes when you’re in it, you believe it; then when someone calls you on something from the outside, you can’t believe it because you’re in it. But actually it is true. Sometimes you’re so close to the work that you don’t see that you’re acting in a certain way. And when people call you on it, it makes no sense, but it makes sense to everyone else. I think that’s a healthy tension. Self-awareness is the highest value you can have as an industry, a company, or a leader.

There’s this mantra in Silicon Valley — and you have definitely espoused it — of “failing your way to success.” Do you think that has a different message now with all these big companies like WeWork actually failing after being extremely overvalued?

Well, the companies haven’t failed. Valuation is a very tricky thing. It’s all fake until it’s real. Failing your way to success doesn’t mean have excess, and have a private jet, and a hot tub in your office on the way to success. I just think the acceptance of failure is one of the magical things about Silicon Valley. You can have an idea, think it’s going to work, try it, it doesn’t work, and you’re not blacklisted from that industry. That doesn’t mean that if you abuse your users, or you abuse policies, or you hide things from people, that that’s okay. That’s the bad type of failure. I’m sad every time I see a Theranos or a WeWork story. It puts a bad name to an industry with a lot of earnest people who are working tirelessly to create the next thing you will love.

Do you think the main thing people want in Silicon Valley is to create the next thing people love, or do you think it’s to just get as rich as possible?

I don’t meet anyone who starts a conversation with “I want to be as rich as possible.” I would not be able to recruit people if the pitch was “Let’s get as rich as possible.” It doesn’t work that way. Do people want to be very successful? Of course. They’re humans. It’s a very type-A-driven culture, meaning people want more. They want growth. More is more. But I don’t know a lot of people who get into the game because the probability is so low that they’re going to be a Gates or a Bezos —

Or a you?

I’m not like Gates and Bezos. They’re a different order of magnitude. How could you possibly get into the game with the expectation that that’s going to happen to you? You have to do it because you love it. Of course, there’s a game that says, “How can I be part of the next big thing?” Because even if you’re not Bezos, being part of Amazon early is probably a pretty good deal.

Everything’s really expensive, and there’s only seven by seven miles of the city. You’ve got more people piling in, so prices are going up.

You still live in San Francisco?

I do, yeah. Same house I’ve lived in since the beginning of Instagram.

How has that changed around you in the past decade?

It’s gotten a lot more expensive. I’ve seen the development of neighborhoods that used to be kind of rustic and full of nonwhite tech people change dramatically. I guess you’d call it gentrification. I’ve seen an enormous amount of construction. But the funny thing is, the culture of the place hasn’t gotten any fancier. Everything feels pretty constant but with an enormous influx of people, so everything’s packed. It feels like, in New York, there are thousands of restaurants of a certain level that are hard to get into. But in San Francisco, you’ve got four. There’s a line down the block. There hasn’t been a requisite increase in the supply of these interesting things to go do, but there’s been this enormous increase in demand. Properties are probably the one thing that’s changed the most. When we bought our house, it was worth X, and now it’s 2X. There’s nothing fundamental about my home that’s changed that should make it worth 2X.

But it gets back to that idea of Instagram being worth a billion at sale and $100 billion now, numbers that don’t make any sense, kind of.

Those numbers make sense.

Well, they make sense in terms of revenue, but people can’t wrap their minds around quite how much money has been poured into this industry, and that’s why there’s this anti-tech, populist sentiment that’s bubbling up.

Socialist.

Yes. Inequality has created this new phenomenon of popular socialism in America. You’re obviously very pro-business. You’re pro-growth. You’re pro–make as much money as possible, get as many eyeballs as possible. Do you think that has contributed to that populist sentiment?

Sure. Some of the smartest people I know both believe in capitalism, which I do, and also believe that capitalism is broken in a bunch of different ways that leave specific groups behind. But does that mean I think we shouldn’t have a place in the U.S. where people with no resources should be able to take chances? I might have had a few thousand dollars in my bank account at the time Instagram sold. No one’s crying for me. You should be able to take a chance and build something of value for the world that should be able to grow and be worth a lot and use that to give back socially. I don’t just mean philanthropy. I mean, like, now we have this platform. How can we help people at scale? We tried really hard to do that, to be a force for good. So, yes, I understand that, if you look at the numbers, wealth and inequality —

It’s extreme inequality, the Bezoses of the world, as you mentioned. The extreme inequality of the richest one percent, or even .001 percent.

But also — I’m not making an argument for Bezos, but everyone loves Amazon.

Well, not everyone loves Amazon anymore.

Sorry, I shouldn’t say everyone. A lot of people. The only reason Amazon is as big as it is is because people buy from it. That’s my point.

Oh, I know. But then you hear these stories about people dying at the Amazon fulfillment centers shipping packages while other people are forced to continue to work around them — literally having a heart attack on the floor, packing boxes or whatnot. These stories proliferate, and there could be a real backlash.

The trend I see is that people will have a social agenda they’ll talk about over dinner or coffee, but they still use the company. I’m not saying there’s this giant hypocrisy right now; I don’t have proof for that. I’m just saying I’ve seen more of it. I think it’s brilliant that if you disagree with a company’s values or how they act, you don’t use them. But my goal when we were building Instagram was “I hope people think that what we’re doing is good.” I know there are some side effects, and we’re working our best at keeping those side effects from proliferating. The best companies are not the companies with no side effects. They’re the company with the least side effects. You do your best to mitigate it.

But take something like Lyft, which has been inundated with lawsuits from women accusing the company of mishandling their sexual assault complaints against drivers. All these technologies start off with these wonderful promises of making our lives more seamless and easy; they succeed, but they don’t account for any of those potential downsides.

I guess what’s your counterfactual? That they shouldn’t exist?

That the profits they’re making are at the expense of the monitoring of the experience. That the extreme profits that we hear of are an abnegation of responsibility.

That’s interesting. Okay, I get it.

Would you agree?

When I look at the margins — meaning the percentage gap between revenue and costs, the profits — in technology, it’s enormous. I have often thought that controlling costs by not hiring a ton of people to, like you say, protect X, Y, or Z allows you to flip it and say, “Man, there’s a lot there to go invest.” So what an interesting opportunity, if you’re still profitable, to go do the hard stuff. I’ll give you an example. On Instagram, this is not exactly spending money, but it’s giving up money: Being able to turn off comments is very clearly negative for engagement. People use it less because there are fewer comments going back and forth bringing you back into the app to see “Hey, what did someone say?” Then you browse your feed, and you see an ad. We made a bunch of these decisions. Being alerted when you’ve spent a certain amount of time on Instagram — very useful to keep people relatively safe, but not pro-revenue. So that is investing some of that margin. I agree with you that there are enormous opportunities for companies to take that margin and invest it in the safety of their communities or their companies. I’m not familiar with a lot of the cases you’re talking about. I’m being careful because I really don’t understand those specific stories.

That, as a concept, applies to many things.

The problem is that with a lot of these companies, everyone is paid in stock, effectively. If you feel like you have to manage your stock prices in any way, especially once you’re public, growing that margin, or at least protecting it from declining, matters. So the incentive system is not set up.

Do you think regulating that incentive system in a governmental way might help mitigate some of these problems?

There are certain industries where they cap margins. So, for instance, insurance is one of these things: You’re not allowed to make more than a certain amount because that would imply that you’re somehow taking advantage of people. I don’t actually know the exact rules, but it’s not out of the question. I’m not sure that’s a policy proposal I’m putting on the table right now.

So your soon-to-be son will be 10 in the next decade. What do you hope for him and your daughter for this next decade?

No. 1, I hope the world does something serious about climate change.

Socially, I hope the division that we have and the partisanship — not even politically, but just in society — that we figure out a way to come together.

Because either we solve them, or they solve themselves in pretty ugly ways, because the system has a way of working itself out.

What’s an ugly way? A war?

If you look at the history of populism, it usually arises around great wealth disparity and social tension. Things like the freedom of the press go away. Often wars happen with other countries, sometimes civil wars, violent class war. I’m not predicting any of these things; I’m just saying that history shows it’s not good for humans when you’re in this state.

What do you think the role of social media will be in solving those problems?

Right now, it seems that we live in our own little bubbles on social media and we follow the accounts we believe in. You’re not exposed to other opinions. That, to me, is a problem that’s well within the reaches of the folks running these companies.

So is it possible for a technology company to actually fix that problem?

It is possible, yeah, but I guess my point is these policy decisions on things like political advertising or fake news are incredibly important for society. The outcome of those decisions will chart the next chapter of this polarization. You asked about ten years in the future: I hope the leaders of these companies and the folks that regulate them on the outside come to a productive conclusion that helps that problem. I decided when we’d been doing Instagram for many years, [and] we’d won on a bunch of different relative measures of winning, What do we want to have our legacy be here? And we worked a lot on kindness — like, a lot. That was really important to me, to feel like we left a company that was actively trying to make the internet a better place.

Would you say Zuckerberg made the right call in saying he won’t fact-check or monitor political ads?

I’m not going to give you my view on whether he made the right call, because he has way more information about the problem he’s facing. What I believe is that it’s very difficult to run these platforms, because you have lots of stakeholders and you’re trying to get it right. These companies both want to be neutral, and they want to be responsible. Sometimes being neutral comes at the expense of the other, and that’s a hard tension and it’s not clear to me that there is a specific right answer there.

What do you think the media gets wrong about Zuckerberg?

I really do believe he believes he’s doing the right thing at all moments.

I don’t agree with him on everything. Nor does everyone, clearly. But I believe, in his heart of hearts, he does believe that what he’s doing is the right thing for society. I think some people sometimes paint ill intent. I don’t think that’s true.

*A version of this article appears in the November 25, 2019, issue of New York Magazine. Subscribe Now!

Now food is created specifically for Instagram, as with @vibrantandpure’s “Unicorn Toast” (cream cheese, natural food colorants, bread) in 2016.

Now food is created specifically for Instagram, as with @vibrantandpure’s “Unicorn Toast” (cream cheese, natural food colorants, bread) in 2016.

@Franciscus’s first Instagram post, March 2016.

In April 2012, Systrom and Krieger agreed to sell Instagram, with all 13 employees, to Facebook for $1 billion. At the time, it was Facebook’s biggest acquisition.

@Franciscus’s first Instagram post, March 2016.

In April 2012, Systrom and Krieger agreed to sell Instagram, with all 13 employees, to Facebook for $1 billion. At the time, it was Facebook’s biggest acquisition.

Beyoncé routinely makes news with her account; her 2017 pregnancy announcement was the year’s most-liked post.

Now there are countless influencers, including @lilmiquela, who is computer-generated.

Instagram launched its version of Snapchat’s Stories. As Systrom admitted at the time, “They deserve all the credit.”

Systrom and Krieger abruptly left Facebook in 2018 to “explore [their] curiosity and creativity again.” It was later reported that they left owing to tensions with Facebook over privacy and Zuckerberg’s desire for control.

Beyoncé routinely makes news with her account; her 2017 pregnancy announcement was the year’s most-liked post.

Now there are countless influencers, including @lilmiquela, who is computer-generated.

Instagram launched its version of Snapchat’s Stories. As Systrom admitted at the time, “They deserve all the credit.”

Systrom and Krieger abruptly left Facebook in 2018 to “explore [their] curiosity and creativity again.” It was later reported that they left owing to tensions with Facebook over privacy and Zuckerberg’s desire for control.

On June 2, 2019, Spencer Tunick took this shot of nude models holding nipple cutouts in front of Manhattan’s Facebook office to protest the ban on showing female nipples, which he believes hurts artists.

On June 2, 2019, Spencer Tunick took this shot of nude models holding nipple cutouts in front of Manhattan’s Facebook office to protest the ban on showing female nipples, which he believes hurts artists.