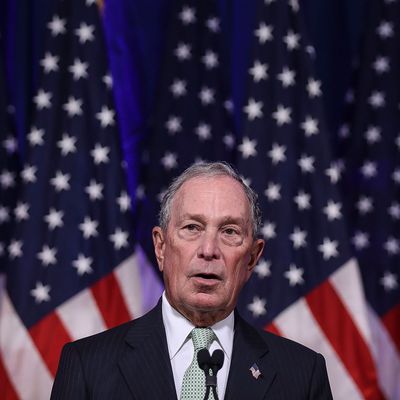

The other day I assessed one theory for how Michael Bloomberg might imagine he’s going to win the Democratic presidential nomination at this late date: He’s gambling, Alex Pareene suggested, on a “brokered convention” controlled by his “Establishment” friends turning to him. I found the theory unpersuasive, mostly because the arrival of Bloomberg’s wallet in the race is more likely to winnow than scramble the field, letting someone else nail down the nomination, instead of creating a deadlocked convention (which would not, in any event, regard Bloomberg as the party’s savior).

But Pareene’s theory strikes me as more plausible than the one penned by John Ellis for CNBC, which suggests panicked Democrats will leap en masse onto Bloomberg’s bandwagon because he’s the only remaining electable candidate in the field after the early contests. Here’s the scenario:

Democratic voters nationally have been moving inexorably toward the view that the party should drop its ideological prerequisites and nominate the most electable candidate, period …

There are two ways things can go in the “electability” half of the bracket. Biden can win by default. (“There is no one else more likely to beat Trump, so we might as well throw in with Joe.”) Or he can get crushed in Iowa and New Hampshire by a 37-year-old gay mayor from South Bend, Indiana, and as a result, watch his candidacy collapse. The latter outcome would leave Buttigieg as the commander of the “electability” army, which (assuming the polling is accurate) enjoys an overwhelming numerical advantage over the “progressive” battalions.

It’s on the latter scenario that Mr. Bloomberg’s candidacy hinges. His handlers are presuming that having seen Mr. Biden dispatched and Mr. Buttigieg all-but-anointed, the Democratic primary electorate in the Super Tuesday states (and beyond) would recoil with buyer’s remorse and scramble to find a more “suitable” (meaning “not gay,” although no one will ever admit it) replacement.

And there waiting for them, with literally billions of dollars ready to spend and open arms, would be Michael Bloomberg.

The underpinnings of this rickety argument structure bear examination. Candidates tend to do better in electability metrics when they are better known and demonstrating popularity in their own party. If, say, Elizabeth Warren swept through the early states, the odds are very good that she’d look as “electable” as Biden looks right now. Ellis seems to assume (based in part on Nate Cohn’s analysis) that progressive candidates are less electable by definition because they don’t appeal to the white working-class voters who will determine the winner of the Rust Belt battleground states and hence (according to Cohn) the Electoral College.

But is there any way on earth that multi-billionaire Michael Bloomberg — pro-gun-control, anti-fossil fuel, Wall Street-oriented Michael Bloomberg — is going to do better among midwestern white working-class voters than, well, anyone else? The fallacy that “centrism” is what these voters want is fully exposed here: Why are these voters attracted to Donald Trump if what they really want is someone like Mike Bloomberg, his polar opposite in the world of New York politics and culture? Beats me.

Ah, yes, but then there is Bloomberg’s wealth and reputation for competence:

Calm, competent, uncharismatic, efficient, former Republican, ruthless billionaire Michael Bloomberg, with an unholy host of political consultants and pollsters ready, willing and able to fan out across every last cable news show to explain why, beyond a shadow of a doubt, Mike Bloomberg was the most electable Democrat in November. (Maybe the most electable candidate in the history of mankind, if it was late enough at night.)

Oh, I don’t know. Was there ever a presidential effort with a larger entourage of “genius” strategists and consultants on the payroll than Jeb Bush’s Hindenburg disaster of a candidacy in 2016? He was absolutely humiliated. Marketing sizzle can accomplish some things, but you have to have the steak, and among Democratic primary voters, Bloomberg isn’t what they’re hungry for, as Ellis concedes. And the idea that he personifies electability is strange. Yeah, his money is impressive, but it’s conventional wisdom in political science that money doesn’t matter a great deal in a presidential general election unless it’s all but uncontested, and we know Trump is going to have a giant bankroll of his own. Which Democratic constituency is he going to get all energized to go the extra mile? African-Americans? I don’t think so. Women? Probably not.

In the end, Ellis’s scenario depends on a Democratic Party in a full electability panic, which it probably shouldn’t and won’t be in, turning to a candidate that most Democrats don’t like and don’t even consider electable. It may be too late for this advice, but Bloomberg should save his money, or better yet, spend it on the many down-ballot candidates who could use it to win.