There are some intraparty arguments that Democrats perennially rehash, as though they were a kind of ritual. Bitter Twitter fights over why George McGovern lost, whether “neoliberals” are real or a superstition, and who was the best candidate in the (never-ending) 2016 Democratic primary mark the passing of blue America’s seasons.

But it’s possible that no intra-Democratic-pundit dispute recurs with more grim regularity than this: Should the party prioritize winning over swing voters, or inspiring sympathetic nonvoters? Or, more succinctly, is the key to winning power persuasion or mobilization?

The animating premise of this debate — that there is an inescapable tension between appealing to swing voters and turning out nonvoters — has always relied less on hard evidence than some progressives’ (wishful) speculation. Swing voters, by definition, do not share liberal Democrats’ worldview. The former may not by consummate centrists, or adherents of any particular ideology. But their inability to recognize the hateful extremities of the modern GOP marks them as a different species of political animal — and thus, potentially hostile to values and policies that progressives hold dear.

Nonvoters, by contrast, are a less obviously unrelatable in their outlook. Liberals can point to the demographic composition of the nonvoting population — which is disproportionately low-income and nonwhite — and tell a plausible story about how the Democratic Party’s failure to embrace a more progressive agenda on poverty, inequality, and racial justice is costing it at the ballot box. Offer nonwhite, low-income nonvoters a clear choice (not an echo) and they will enter the electorate en masse. Which is to say, stop worrying about offending the median Rust Belt swing voter; unapologetically endorse progressive stances — including on so-called culture-war issues — and the many will prevail over the few.

There are more sophisticated (and substantiated) versions of this argument. For example, there is evidence that Democrats’ failure to pass pro-labor policies while in power (as opposed to touting them on the campaign trail) has cost their party support among working-class Americans. As institutions that cultivate the class consciousness and civic participation of working people, trade unions appear to make their apolitical members more left-leaning and their left-leaning members more politically active. It’s very plausible that other progressive community institutions such as Planned Parenthood fulfill a similar function.

In other words, there’s some reason to think that the class and social position of nonwhite (and/or working-class) nonvoters make them potential constituents for progressive politics, given sufficient engagement from trusted community institutions. But this does not mean that politically disorganized, low-income, and/or nonwhite Americans are especially likely to subscribe to the left-wing economic views that vulgar Marxists would ascribe to them — let alone to the across-the-board social and racial progressivism that is most commonly found among highly engaged, highly educated Democrats of all colors and income levels.

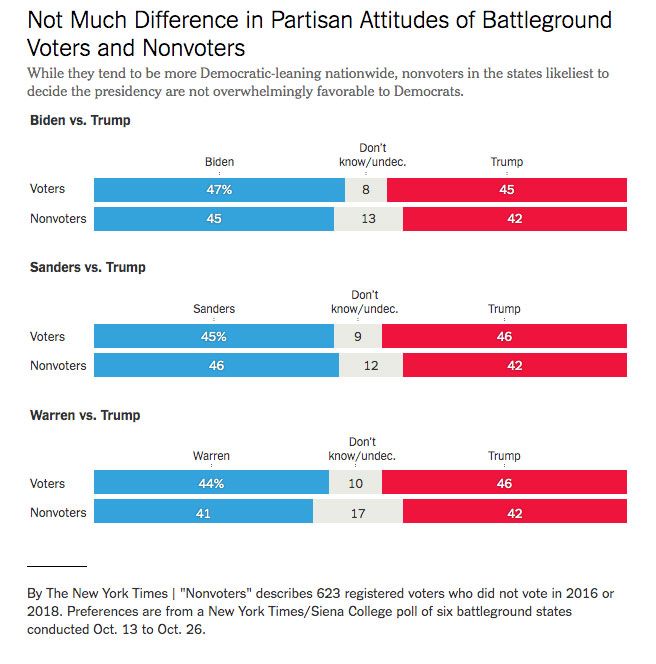

A recent New York Times Upshot/Siena College survey of nonvoters in six battleground states speaks to this point. The survey’s headline finding is that nonvoters in these disproportionately white states are only marginally more Democratic-leaning than the regular electorate. This appears to be a reflection of Trump-era sorting along lines of education; now that non-college-educated white voters are overwhelmingly Republican, and well-educated suburbanites lean Democratic, uniformly high turnout isn’t necessarily great for Democrats in Rust Belt states.

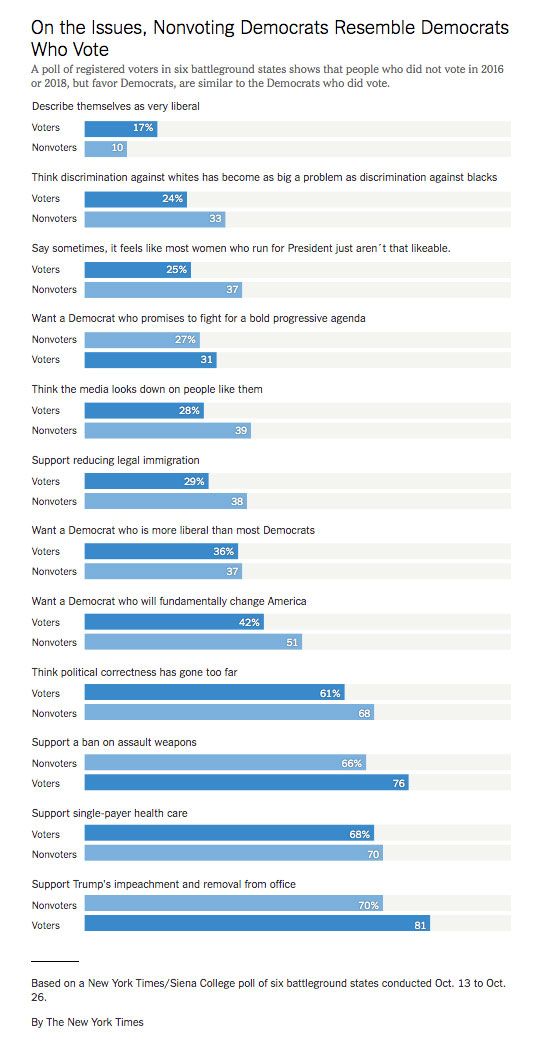

But the poll also suggests that nonvoting African-Americans are, on average, less Democratic than those who vote regularly, and that nonvoting Democrats are less ideologically progressive — especially on (so-called) social issues — than their co-partisans. The latter fact is especially dissonant with conventional wisdom: Despite the fact that the population of nonvoting Democrats is much more African-American and Hispanic than regular Democratic voters, the former were both more likely to favor reducing legal immigration, and to agree that “discrimination against whites has become as big a problem as discrimination against blacks.”

And yet, while nonvoting Democrats were more ideologically heterodox, and averse to identifying as “liberal,” they also expressed some sentiments that will hearten leftists who imagine them as latent revolutionary subjects: 51 percent of Democratic nonvoters said they wanted a presidential nominee who will “fundamentally change America”; only 42 percent of regular Democratic voters said the same. Meanwhile, nonvoting Democrats were also more likely to support single-payer and to approve of Bernie Sanders, who boasted a higher “very favorable” rating among such Democrats than Joe Biden or Elizabeth Warren. In fact, Sanders was the only Democratic candidate to enjoy higher favorability among nonvoting Democrats than those who regularly show up at the polls.

One upshot of these findings: There is much less tension between the preferences of undecided voters and nonvoting Democrats than progressives often suggest. Independent voters in the Rust Belt tend to view the Democratic Party’s positions on health care and taxes more favorably than its stances on immigration; nonvoting Democrats appear to feel the same. A majority of undecided, non-college-educated voters in the Times poll expressed a preference for “moderate” Democrats over liberal ones, but also for single-payer health care and “fundamental, systematic change to American society” over a return to politics as normal. Nonvoting Democrats espoused the same idiosyncratic preferences.(Notably, undecided, college-educated voters in the Times survey were hostile toward single-payer health care and more disposed toward a return to normalcy than fundamental change. But only 35 percent of undecided voters in the poll were college-educated.) Taken together, the Times’ findings suggest that “unreconstructed” Sandersism — which is to say, a bold, anti-Establishment message focused narrowly on health care and inequality — might be the party’s best bet for reaching nonvoting Democrats and swing voters alike.

All of this said, there is one reason to take the Times’ survey with a grain of salt: Its definition of nonvoter is a very specific one. Since unregistered nonvoters tend to be exceptionally difficult to poll, the survey’s pool of nonvoters consists entirely of Americans who registered to vote, but didn’t turn out in the last two federal elections. This is a distinct population from eligible 2020 voters who were not even registered in 2016 or 2018 — either because they were completely disconnected from the political process, or simply too young to cast a ballot. The latter category of nonvoters may be more promising to Democrats, and more receptive to across-the-board progressive messaging. If their generation’s behavior in 2018 is any guide, a lot of Gen-Zers and young millennials will register to vote for the first time next year. Given their cohort’s views in opinion polls, it’s conceivable that unabashedly liberal messaging would be conducive to bringing them into the ballot booth (and/or steering them clear of third parties). Separately, even if moving left on social issues as such is not a panacea for mobilizing unreliable Democratic voters, doing so in discrete policy areas might be. To take just one example, a recent poll from Data for Progress and Tufts University found that the legalization of marijuana enjoys overwhelming support among voting-eligible Americans who did not cast a ballot in 2016 or 2018.

Nevertheless, the available evidence indicates that the Democrats’ best pitch to left-leaning nonvoters and undecided voters are one and the same: We’re a party of “moderate” outsiders who believe that health care is a right, and that Washington’s in need of fundamental change.