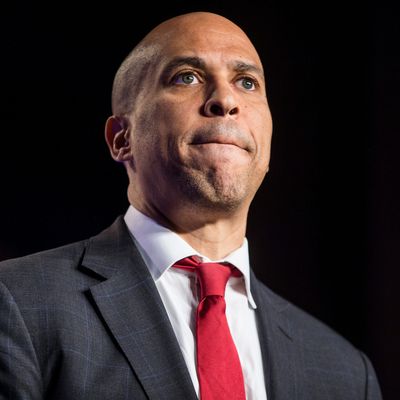

On one level, New Jersey senator Cory Booker’s withdrawal from the 2020 presidential contest wasn’t surprising at all. He failed to meet the Democratic National Committee’s polling thresholds for participating in last month’s candidate debate in Los Angeles and tomorrow’s in Des Moines.

In the RealClearPolitics national polling averages for Democratic candidates, he is in tenth place with 1.8 percent. He is only doing marginally better in his two most crucial states, Iowa (seventh place with 2.7 percent) and South Carolina (sixth place with 3 percent). He has been trailing in the money sweepstakes for a while; his $6.6 million haul in the fourth quarter of 2019 was his best yet, but far below such back-of-the-pack rivals as Andrew Yang ($16.5 million) and Amy Klobuchar ($11.4 million), not to mention the Big Four of Bernie Sanders ($34.5 million), Pete Buttigieg ($24.7 million), Joe Biden ($22.7 million), and Elizabeth Warren ($21.2 million), or the billionaire self-funders Tom Steyer and Michael Bloomberg.

And indeed, it’s money that Booker himself cited as the problem, along with exclusion from the debates:

But on another level, the failure of Booker 2020 remains a bit of a mystery. He entered the contest with as much Senate experience as Elizabeth Warren (and more than Kamala Harris), and a significantly stronger record of municipal service (as mayor of Newark) than Pete Buttigieg. He has been in the national media spotlight since his first, unsuccessful race for mayor of Newark back in 2002 (he won the job four years later). Famously eloquent and upbeat, he was a progressive Democrat with just enough ideological heresy in his record (e.g., support for school vouchers) to make him interesting to pundits and attractive to donors (particularly those in nearby Wall Street). He was particularly strong on one of the top issues of 2020, criminal-justice reform, and had a signature “baby bonds” proposal that gave him an all-purpose answer to the key problems of structural inequality and racism. At the age of 50, despite his extensive résumé, he was one of the younger candidates in a relatively old field.

His 2020 strategy made abundant good sense, replicating as it did the successful 2008 strategy of Barack Obama: Build on his retail political skills to overachieve in Iowa, and then achieve a breakthrough in the majority-black Democratic primary electorate of South Carolina. Early reports from Iowa suggested he was building a formidable organization there. As my colleague Gabriel Debenedetti noted in June of last year, this approach played to his apparent strengths:

Booker’s early and intense focus on organizing the state — which he’s now visited four times — is the result of his campaign’s calculation that in-person campaigning and field organization are his strengths, rather than the national-media-narrative game.

But Booker also took advantage of his national opportunities, too, delivering probably the most consistently strong performances in the Democratic debates from June through November. So what went wrong?

In an August column puzzling over Booker’s inability to take flight, the New York Times’ Michelle Goldberg put her finger on something often suspected about him:

Booker’s problem may be that he’s too well known by political journalists to be exciting, but too little known by most voters to be a household name.

His “story” was old hat to observers who had been watching him closely for years, but he still had to sell it to regular Democratic voters who had never heard of him.

Booker had another problem that didn’t confront Barack Obama: the handicap of another credible African-American candidate, Kamala Harris, who had the same strategy and something of the same profile as the New Jersey senator. When Harris’s campaign took flight last summer after a strong debate performance marked by her direct challenge to Joe Biden’s record on racial justice, it seemed to diminish Booker’s prospects.

But ultimately both Harris and Booker succumbed to the common problem — absolutely crippling in South Carolina and (presumably) other important states with large minority populations — of having little appeal to their fellow African-Americans. And even though Harris preceded him in dropping out of the race, Booker has still lagged far behind white candidates among black voters, as a new Ipsos–Washington Post survey showed. With a mere 4 percent of African-Americans in his camp (the same percentage held by Mr. Stop-and-Frisk Michael Bloomberg), Booker was outgunned by a margin of 12-to-1 by Joe Biden (48 percent), five-to-one by Bernie Sanders (20 percent), and better than two-to-one by Elizabeth Warren (9 percent).

In some respect, the Booker candidacy represented a Catch-22 in that he could never gain enough support to develop the kind of buzz that might have lifted him into the top tier of candidates. He was, for example, the kind of candidate — with a message of unity, common purpose, and even love — who could have, like Obama before him, exhibited some serious trans-partisan appeal at a time when his party is desperate to expand its base. But he never had enough of a clear public profile to make him look “electable” against Trump. Despite all those years in the spotlight and a long and vigorous campaign, Morning Consult still shows that 37 percent of Democratic primary voters don’t know enough about Cory Booker to form an opinion of him.

His departure from the 2020 contest leaves just one African-American in the race, Deval Patrick, who isn’t exactly setting the campaign trail on fire, and a total of three nonwhite candidates, including Andrew Yang and Tulsi Gabbard.

Booker is still young enough to make this just the first of multiple presidential runs. Indeed, had he not ruled out becoming the running mate of any male presidential nominee, he’d be at or near the top of veep speculation (and could yet be if a woman is the nominee). More likely he’ll run for reelection to the Senate (under New Jersey law he was able to pursue both reelection and the presidency simultaneously) and work on somehow reigniting interest in his career and ideas in the commentariat while becoming better known to the voters who largely ignored him in 2020.