It may be fleeting but I sensed a small, distinctive undercurrent of normalcy this week in our political system. A long-weakened party, faced with an insistent and ascendant insurgency from its populist wing, actually gathered itself together and acted in collective self-defense. What the Republicans were incapable of doing in 2016, the Democrats are attempting in 2020. As the GOP has dissolved into a crass husk of a media organization, dedicated to a cult figure, there’s life in the rickety, old Democratic Party structure after all.

What struck me first was the swift and joint decision of both Pete Buttigieg and Amy Klobuchar to put party (and country) before candidacy. Their campaigns had not quite been nailed to the perch Tuesday night, but there was no credible way forward to victory for either. (If only Trump’s rivals had exercised that discipline in the GOP primaries four years ago). Mayor Pete’s pretty flawlessly executed strategy didn’t fail; in Iowa and New Hampshire, it worked beyond anyone’s original expectations. It just ran into the incompetence of the Iowa Democrats (denying him a triumphant news cycle), the Bloomberg bubble, and his persistent failure to break through with black voters. Klobuchar followed suit, having never quite gained the authority or personal appeal she needed to break out. Then the day after Super Tuesday, Bloomberg got out — a man who had endless cash in hand but also exercised the kind of self-discipline no Republican in 2016 managed. Better still, Bloomberg has committed to throwing vast resources to defeat Trump this fall — and his ads, taunting, brutal and simple, have been the most inspired of the campaign so far.

This was not the GOP in 2016 — unable to winnow the field and coalesce behind a single opponent to Trump, and then staggering backward into submission. This is the Democrats in 2020, finally a party capable of operating with some institutional authority. Here’s a headline you don’t often see: “Democrats Not in Disarray!”

And it was even more exciting that black voters were indispensable to this sudden veering toward pragmatism. If you peruse left Twitter or read a lot of op-ed columnists at big papers and sites, you’d be under the impression that black America has never been more aware of the iniquity of the entire American project, more conscious that no racial progress had been made at all, and is more open than ever to revolutionary politics. But, with the exception of younger black voters who went for Bernie, it turns out the vanguard of the new critical race activists on campus and in elite media represent almost no one but themselves.

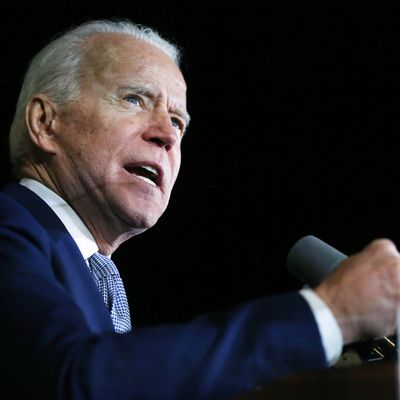

In fact, presented with a choice between an intersectional revolution against “white supremacy” or a doddering but familiar face promising mild reform, African-American Democratic voters emphatically chose the latter. Joe Biden — that mass-incarcerating friend of actual white supremacists in the Senate — won 63 percent of the black vote in Virginia, 72 percent in Alabama, and 60 percent in Texas. In fact, Biden won the African-American vote in every single contest, if not by the same staggering margins.

The gulf between what media elites say about African-Americans and what actual black normies believe even began to sink in with the wokerati. Here’s a nearly poignant epiphany from Ibram X. Kendi, the radical black social constructionist I wrote about recently:

I’m reflecting on how seemingly divided Black politicians are from Black intellectuals and activists. It seems as if more Black politicians have endorsed Biden or Bloomberg. It seems as if most Black intellectuals and activists have endorsed Sanders or Warren.

Nearly there. But what Kendi can’t yet quite grasp is that the reason black politicians aren’t woke is that their voters aren’t either. Black America is not a breeding ground for postmodern theories of intersecting oppressions. Outside the Bernie youth cohort, it’s socially conservative, politically savvy, and more determined to beat Trump than to embrace ideological purism.

The same could be said for Elizabeth Warren’s cringe-inducing campaign, in which she veered left not just on economics but on culture, celebrating transgender children, lamenting the patriarchy’s relentless grip, pledging to end systemic racism, and so on. In debate after debate she deployed feminist identity politics to portray herself as the candidate of women. For upper-middle-class, left feminists, she was the dream candidate. But for normie Democratic women voting on Super Tuesday, she was worth 15 percent support, while Uncle Joe, with all the baggage of his handsiness and his conduct toward Anita Hill, won more than twice that much female support. For good measure, the candidate most in tune with intersectionalism and one of the most committed to racial justice, was rejected by 95 percent of black Democratic voters.

Was it sexism that did in her candidacy? Of course there was sexism; it’s everywhere. And maybe Hillary Clinton’s shambolic performance last time around gave people pause about again putting up a woman against Trump. But there was also a lot more to it. Warren’s policies were way to the left, her earlier debacles (like the DNA test) revealed terrible political judgment, and her classic persona as a know-it-all Harvard professor with a plan for everything was almost identical to that of every earnest Democratic candidate who has lost in the last few decades.

But many of her prominent backers can still only see her as the victim of misogyny. Jessica Valenti lamented that “we had the candidate of a lifetime … and the media and voters basically outright erased and ignored her.” In fact, in four critical debates, including those in January and February, Warren was given more time to speak than any other candidate. Valenti went on: “Don’t tell me this isn’t about sexism. I’ve been around too long for that.” Shaunna Thomas, executive director of the progressive group UltraViolet, chimed in: “It is the media’s sexism that determined Warren’s fate.” In fact, puff pieces on Warren abounded. And it seems telling to me that no one seems to be writing tweets or columns ascribing Amy Klobuchar’s withdrawal to sexism or Pete Buttigieg’s exit to homophobia.

We have also learned something important about the electorate as well. The revolution Bernie promised required a massive new surge of young and nonvoters to swarm the polls for a radical transformation of politics. I wrote last week that in Britain, too, the promise of Jeremy Corbyn’s Labour Party was that it might generate a new wave of younger voters who would change the shape of the electorate. And polling has long shown a big, sustained lead for Corbyn and for Sanders among the under-30s. But in the last two British elections, no such youth surge was visible. And on Super Tuesday, although Bernie won a massive 60 percent of the under-30s, that demographic made up a sad 13 percent of the electorate. And this was not a fluke:

In North Carolina, a state that, like Virginia, will figure significantly in November, the numbers were pretty much identical to VA: 13 percent of voters were under 30, down from 16 percent four years ago, and Sanders took 57 percent of them, down from 69 percent. In Alabama, only seven percent of voters were between 17 and 29, compared to 14 percent in 2016. (Sanders did up his chunk of that vote to 60 percent.) In Tennessee, just 11 percent were under 30, down from 15 percent four years earlier.

What about all those previous nonvoters who were about to flood the polls for Corbyn and Sanders? In Britain, they turned out in droves in the 2016 election and made Brexit happen. In the biggest turnout states last Tuesday, it wasn’t Sanders who got people to the polls — it was Biden, showing that large turnouts need not mean left-wing triumphs. The biggest turnout in British electoral history — the 2016 Brexit referendum — brought in swathes of new voters, as did the Trump campaign in the same year. Most of them, of course, were on the right.

I think Bernie Sanders could have won against Trump last time around. And the following year, Corbyn nearly won the British election. The endless and slow economic recovery from the financial crisis took time to pick up some steam, and by 2016 the effects were only beginning to register in the broader consciousness. But since then, it seems, as the recovery in both the U.S. and the U.K. has continued, as unemployment has dropped to new lows, as some measures to restrict mass immigration have calmed some of the anxious, the mood has shifted. Timing is everything in politics. Maybe left populism just didn’t get lucky.

Yes, we still have the problem of lovable old Joe being a touch like Abraham Simpson, along with all his usual gaffes and meandering and his family’s history of grifting. But his relative moderation in what looks to be a slightly less populist electorate than a few years ago may give him a chance. Given the alternative, all of us, Democrat, independent, and sane Republican, should seize it. We have a republic to save. And this is not a drill.

The Politics of a Pandemic

The flu epidemic of 1918 is one of those seismic events in modern history that has nonetheless nearly vanished from public consciousness. With any luck, that will remain the case, but I can’t be the only one diving into online research to better understand that sudden, modern plague as the coronavirus spreads.

I kind of knew this in my head, but it was somewhat startling to see in pixel form that up to 675,000 Americans died in a short period of time, in a population of around 103 million. Did that flu have a much higher mortality rate? Alarmingly, no. The rate was somewhere around 2 to 3 percent, about the same as the one coming soon to an ATM machine near you. Yes, the health-care system was far worse back then, and secondary bacterial infections, largely treatable today, were responsible for much of the toll.

But still, controlling a virus this infectious, and managing the fear and panic that might well ensue is not an easy task. In fact, it’s exactly the kind of public-health emergency that requires an actual president, with serious credibility — someone whose word can be trusted, who is not prone to hyperbole, or conjecture, or disinformation. The moment demands a president who understands and respects science, and who can coordinate a global as well as a national defense strategy. And that president we do not have. The luck we have had so far in avoiding a major crisis with this deranged goon in charge may be about to run out.

Worse, the way Trump instinctually responds to a crisis is that of an autocrat. Something this bad is happening on his watch and it might well reflect badly on him so … what to do? Deny it, then cover it up, then blame others. Call it the Chernobyl instinct. Every natural tyrant has it.

More to the point, we know by now that this is how Trump thinks, and it’s directly counter to good public-health policy. We also know it’s essential to communicate transparently, clearly, and carefully when guiding a public through such an ordeal. So Trump used a press conference this week to muse out loud and praise himself, misstate crucial facts, and then on Wednesday night went on Sean Hannity to say he has a “hunch” everything is going to be okay. He still has no clue what his job is, does he?

It’s eerily quiet now, outside the financial markets, and I’ve gotten a few funny looks when I wear my face mask in the airport. But it feels to me like one of those long, silent, calming scenes in the opening of a horror movie. I have shitty lungs, a long history of asthma, bronchitis, and pneumonia, and a somewhat compromised immune system, so perhaps I’m a little bit more jittery than is reasonable. But it’s obscene to refer to possible deaths from this disease as somehow more tolerable because the victims tend to be old, or sickly, or vulnerable in some other way. Life is life. What makes the West more decent than most civilizations is concern rather than contempt for the weak.

And no, we shouldn’t politicize this. But purely as an analytic process, it’s easy to see how this could be the most important moment for this administration. If its core incompetence is exposed in ways even Fox News can’t contain, and the primary victims of the 2020 flu are concentrated among Trump’s older base, the cult might break up a little. On the other hand, a global epidemic in a world that’s evermore interdependent could accelerate the cultural backlash to internationalism. It might wound Trump but reward Trumpism.

Or, of course, God willing, it might also peter out.

Welcoming Aaron Schock

One of the more mischievous things that Tina Brown did when I was working with her at the Daily Beast — for three years that site hosted the Dish — was to insist on my going to the White House Correspondents’ Dinner. That was bad enough. But then she seated me at a table next to then-GOP congressman Aaron Schock. I say mischievous because I assume Tina intuited that Schock was gay and thought therefore he and I might have something in common (this happens at weddings as well and almost never works). Or perhaps she foresaw an excruciatingly awkward evening in which I was supposed to pretend it wasn’t bleedingly obvious to me that Schock was gay.

Happily, at that ghastly schmoozathon, you can easily get up and move around, between or even during servings to air-kiss, greet corporate sponsors, suck up to media honchos, and gawk at the occasional Hollywood B-list celebrity. But I had to start some sort of conversation, so I introduced myself and subsequently watched all the blood drain from his pretty face. After a couple of brief niceties, he turned to his left and talked to the woman seated on the other side (I confess I can’t remember who), and didn’t even look at me again.

He wasn’t being rude. It was quite obvious to me he was simply shit-scared. There are few things that freak out closeted gay men more than openly gay men; there’s often an obvious rapport between us that has to be somehow stamped out. And my own long campaign for marriage rights and open military service probably made him feel even more defensive because of his multiple congressional votes against gay equality. Nonetheless, I felt and feel a certain sympathy for him that most other gay men don’t. Yes, the argument for his rank hypocrisy was and is pretty airtight, and maybe I should have called him out. But I’m also acutely aware that we never truly know who a person is, what experiences might have led them to a given impasse, and what struggles they are trying to overcome. It’s why I have always opposed outing people. Punishing the weak and afraid is a form of self-righteous sadism. Even hypocrites deserve mercy, especially if they are confessing their flaws.

And reading his coming-out letter, published yesterday on Instagram, you can see all the classic syndromes: the deeply fundamentalist upbringing, the conservative politics, the best-little-boy-in-the-world complex compensating for his internal self-loathing, the push and pull of ambition and fear. And I sure wish he had been able in his Instagram post simply to say sorry. It’s hard to give forgiveness to someone who isn’t asking for it.

But he’s a useful and important reminder that with all our progress, the pain of the gay adolescent in a conservative family, school, neighborhood, or church remains. Many internally distressed souls find themselves acting out to compensate, or constructing a fake life in which your integrity, once compromised, can eventually disintegrate altogether. Many of us who are lucky to have left all that behind, who found strength others simply couldn’t, can sometimes forget this agony still exists, even for the younger generations who have grown up in a far more tolerant world. In our more callous or bitchy moments, we mock it. Or we turn some of our own anger at homophobia into hatred for another man trapped in the same syndrome. I’m ashamed to say I was shocked by the story of football star and murderer, Aaron Hernandez, as a recent HBO documentary it laid out. He loved and revered his father but always believed he would never be accepted — and might even be ostracized — by him if he came out as gay. It led him into a terrible dead end. This was not decades ago; it’s very recent. And it’s happening now. Politics can’t change this, and the pain is all the more searing because it is created by and directed toward your own self.

So can we forgive? Can we accept? Can we even welcome such a man into a movement in which he can help others, as he has pledged to do? Yes, of course we can. And for those many gay men and women who have compassion and memories of our own pain and a certain humility, we really must.

See you next Friday.