Derek Chauvin kneeled on George Floyd’s neck for eight minutes and 46 seconds while the handcuffed black man begged the police officer to let him breathe. In response, tens of thousands of Americans took the streets in protest. The fundamental premise of these demonstrations was that George Floyd’s killing wasn’t an aberration — but officer Derek Chauvin’s indictment for that killing was. Which is to say: Egregious abuses of police power are common in the U.S., indictments of police officers for such abuses are rare, and there is a relationship between these two facts.

Over the past week, cops in municipalities across the United States have done their darnedest to prove the protesters’ point.

To be sure, the past few nights of unrest have put many police officers in genuinely dangerous and difficult circumstances. Several have been the victims of unprovoked attacks. Many have performed their assigned duties lawfully and with restraint. But many have not. Over the past 72 hours, videos of audacious police abuse have proliferated so rapidly, subgenres like “cops willfully attacking clearly identified members of the press” are already stocked with a wide range of titles. We’ve seen police pepper-spray protestors for the crime of exercising their First Amendment rights, shoot paint canisters at people seated on their front porch, and throw senior citizens to the ground. In ways large and small, officers have comported themselves as though they are not bound by the laws they’re meant to enforce.

Which makes sense since, by and large, they aren’t.

Cops are legally unaccountable because they’re politically powerful.

Police officers in the United States kill about 1,000 people in the line of duty each year (only four other nations allow their security forces to take so many civilian lives annually — Brazil, Venezuela, the Philippines, and Syria — all of which have much higher crime rates than our country does). According to research from Philip Stinson of Bowling Green State University, between 2005 and April 2017, a grand total of 80 American cops were charged with murder or manslaughter for killing someone on the job. Less than 30 were convicted. In other words: Over that 12-year period, American cops who killed people in a professional capacity faced legal sanction in 0.25 percent of instances. Maybe only one in 400 police killings in the United States are unjustified. But given the myriad indefensible, unpunished police killings that have come to light in recent years, this seems unlikely. And uses of excessive force that result in a person’s death are the exception. Lesser forms of needless physical abuse are ubiquitous and even less likely to result in disciplinary action.

A wide range of fortifications protect abusive police officers from legal accountability. In many cities, police unions’ collective-bargaining agreements are full of provisions impeding oversight and abetting cover-ups. An anti-snitching culture (a.k.a. the “blue wall of silence”) further inhibits investigations. Meanwhile, the Supreme Court’s “qualified-immunity” doctrine has neutered the capacity of citizens to deter abuse through civil lawsuits (more on this point in a moment).

But all of these barriers between criminal cops and justice rest on the same foundation: The immense political power of police officers in the United States.

It is true that police unions shield their members from public accountability through collective-bargaining agreements. And Campaign Zero, an anti-police-violence organization, has proposed many worthy restrictions on what cops can bargain over in contract negotiations. But there are already five U.S. states where police officers have no collective-bargaining rights whatsoever — Georgia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, and Virginia — and none of them are bastions of police accountability. In New York, meanwhile, state law restricts the rights of police unions to negotiate over disciplinary issues. This did not prevent Eric Garner’s killer, Daniel Pantaleo, from retaining his job for five years after the former’s death. (Pantaleo is appealing his dismissal.)

The fact that unaccountable policing persists even where unions are constrained reflects the primary importance of cops’ political power. You can prohibit police from neutering oversight in collective-bargaining agreements. But you can’t bar them from voting as a bloc, donating to campaigns, or lobbying the legislature. And what can’t be won in a contract can often be secured via statute; in Virginia, cops lack bargaining rights but boast their very own bill of rights.

This is not to say that strong police unions don’t enhance their members’ political clout. But unionization is not the cornerstone of their influence. In addition to the power police officers derive from their capacity to vote as a bloc and pool campaign donations, cops boast two sources of nigh-unique political strength:

1) The police are one of the only popular, widely trusted institutions in the United States. There are only three institutions that perennially command a “great deal” or “quite a lot” of confidence from Americans in Gallup’s polling: The military, small business, and the police. Cops command more than twice as much trust in these surveys as newspapers do and about five times more than Congress.

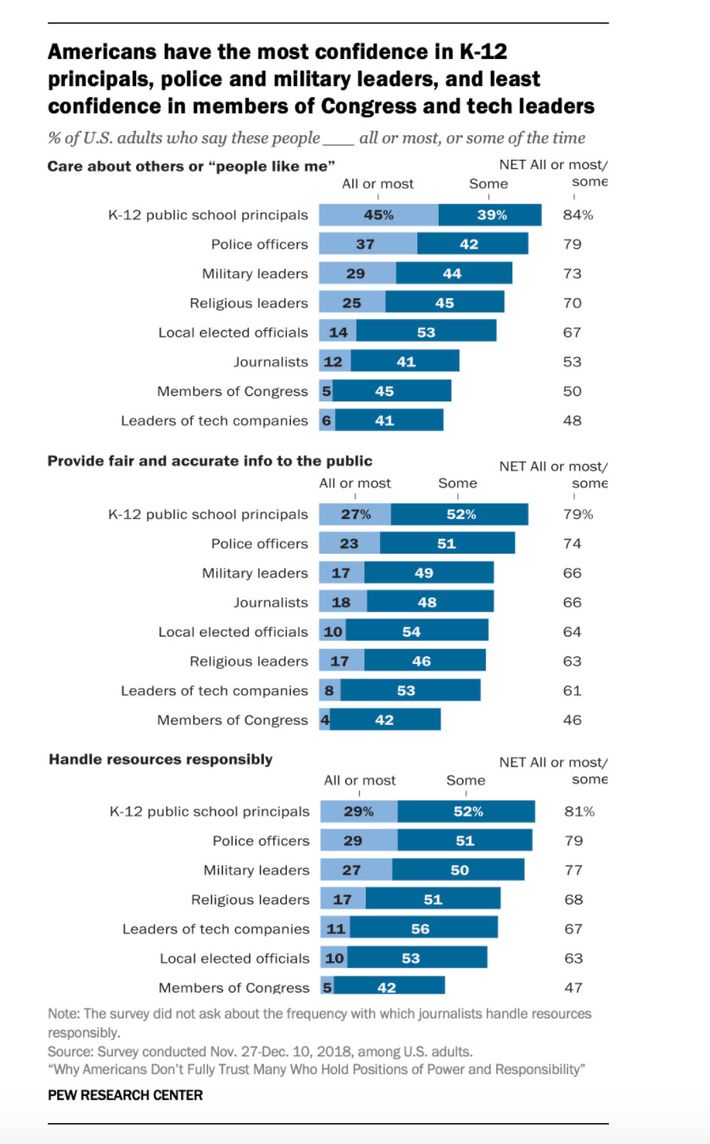

Pew Research’s opinion data affirms Gallup’s findings. In a 2019 Pew survey, only K-12 school principals commanded more public confidence than cops. Some 79 percent of respondents said that police officers “care about them all or most of the time,” while 74 percent said that they provide fair and accurate information all or some of the time. (Granted, “police officers provide accurate information some of the time” seems like an assertion that no one could dispute, but it remains the case that the public expresses more faith in the accuracy of cops’ statements than they do in those of journalists or elected officials).

What’s more, as the Washington Post’s Phillip Bump has illustrated, trust in police is disproportionately concentrated in constituencies with higher-than-average voter-turnout rates, such as the old and registered Republicans.

All this makes crossing the police a risky proposition for elected officials, whether they be mayors, city council members, or prosecutors.

2) Police boast a monopoly on a form of labor that municipalities are profoundly reliant on. To cow elected officials, cops need not rely solely on their claim to the public’s esteem. Although police do not have the legal right to strike, in practice, they have the power to execute work slowdowns that undermine public safety — and thus the standing of democratically accountable politicians. It is true that these quasi–work stoppages don’t always work. When the NYPD organized a slowdown to protest Mayor Bill de Blasio’s response to Eric Garner’s death, incidents of crime fell. But when Baltimore’s police department executed a monthslong “pullback” from the city’s most disadvantaged neighborhoods, a devastating surge of homicides ensued. Small-scale efforts to discipline elected officials by withdrawing law enforcement services from their constituencies are far from uncommon, a reality Minneapolis City Council member Steve Fletcher testified to this week.

To subordinate the police’s prerogatives to the rule of law, reformers will need to erode — or circumvent — these sources of cop clout.

A less reflexively pro-police public is possible.

Of course, protesters are already hard at work at contesting the police’s public image. Recent polling suggests that George Floyd’s killing — and the unrest it provoked — may be affecting a shift in public attitudes on policing. In a Morning Consult poll released Monday, a majority of Americans expressed support for the protests, while 51 percent agreed that “many people nowadays do not take racism seriously enough”; last year, that figure was 41 percent.

A Monmouth University survey produced even more-auspicious results. In 2015, amid the first wave of Black Lives Matter activism, the pollster found roughly half of Americans agreeing that “racial and ethnic discrimination” is a “big problem” in the United States. This week, that figure was 76 percent. Meanwhile, 78 percent said that the anger that sparked these protests was fully or somewhat justified. Most remarkably, after being reminded of the violence that has attended the protests — including the burning of a police precinct — 54 percent of respondents nevertheless affirmed that the actions of the protestors were, in the aggregate, at least partially justified.

Thus, exploiting the ubiquity of cellphone cameras and the reach of social media to raise awareness of police misconduct is a vital endeavor. Political-science research indicates that few things did more to rally the public behind the Civil Rights Act than witnessing the brutalization of nonviolent protesters by southern law enforcement.

Separately, progressives in the entertainment industry may also have a role to play in shifting public perceptions of the police. Judging pop-culture objects on the basis of their supposed ideological merits or heresies can get tiresome. But in some cases, the “woke scolds” have social science at their backs. We live in an atomized, media-saturated society, where televisual entertainment exerts great influence over popular attitudes. Multiple studies have found that the omnipresence of police procedurals on American television — almost all of which cast law-enforcement officials as sympathetic protagonists — has powerfully shaped public attitudes toward the police. A 2015 paper from the journal Criminal Justice and Behavior found that “viewers of crime dramas are more likely to believe the police are successful at lowering crime, use force only when necessary, and that misconduct does not typically lead to false confessions.” It is therefore conceivable that dramas and films that dramatize the pathologies of American policing may help chip away at the public’s reflexive support for cops.

All this said, it’s important to note that public opinion data on the present unrest remains preliminary and somewhat contradictory. Even as voters evinced sympathy for the protestors in several polls, a majority also approved of the U.S. military aiding local police forces in reestablishing order in America’s cities. Further, although the upsurge of protest that followed the shooting death of Michael Brown in 2014 brought Americans’ confidence in the police to a two-decade low, it returned to its long-run average of 57 percent within two years.

Thus, while contesting the police’s popularity is important, the most promising path to near-term change may be navigating around it (progressives have already been doing this by, among other things, galvanizing activists and donors behind left-wing district attorney candidates in low-visibility, low-turnout elections). Fortunately, one of the most formidable barriers to police accountability is also among the least fortified by the police’s political power.

“Qualified immunity” deserves unqualified opposition.

In 1871, Congress passed a Civil Rights Act that empowered Americans to file civil lawsuits against any state official who caused a “deprivation of any rights” guaranteed by the Constitution. Had this law been faithfully interpreted by the judiciary, police officers who abused their constituents would find themselves at great risk of suffering financial damages — no matter how generous their collective-bargaining agreements or how much deference they commanded from elected officials. You wouldn’t need a radical district attorney to make a crooked cop pay for their brutality; any skilled civil litigator would suffice.

But the Supreme Court gutted our right to take cops to court by establishing a doctrine known as qualified immunity, which provides public officials with an all-but-airtight defense against liability claims. The Appeal, a pro-criminal justice reform publication, offers a succinct summary of this malign jurisprudence and its consequences:

The Supreme Court invented qualified immunity in 1967, describing it as a modest exception for public officials who had acted in “good faith” and believed that their conduct was authorized by law. Fifteen years later, in Harlow v. Fitzgerald, the Court drastically expanded the defense. The protection afforded to public officials would no longer turn on whether the official acted in “good faith.” Instead, even officials who violate peoples’ rights maliciously will be immune unless the victim can show that his or her right was “clearly established.” Since the Harlow decision, the Court has made it exceedingly difficult for victims to satisfy this standard. To show that the law is “clearly established,” the Court has said, a victim must point to a previously decided case that involves the same “specific context” and “particular conduct.” Unless the victim can point to a judicial decision that happened to involve the same context and conduct, the officer will be shielded from liability.

… This shortcut has led to some outrageous results. In an opinion filed in March 2019, for instance, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit held that officers were immune from liability for the deliberate stealing of property simply because there was no “clearly established” case law governing the circumstances. In that case, police officers who had executed a search warrant seized about $275,000 in property: approximately $150,000 in cash, and another $125,000 in rare coins, but stated that they had seized only $50,000. In other words, the officers attempted to steal $225,000 while on the job.

The Ninth Circuit dismissed the lawsuit against the officers, granting qualified immunity because it had “never before addressed” whether officers executing a warrant could steal property. And, according to the court, it was not sufficiently “obvious” to police officers that stealing property under the guise of executing a search warrant violated an individual’s constitutional rights.

There is some reason to believe that there is a majority on the Roberts Court to at least scale back qualified immunity. Clarence Thomas has indicated that he believes the doctrine merits reconsideration, as has Sonia Sotomayor. On Capitol Hill, there is a modicum of bipartisan interest in reasserting the plain meaning of the 1871 law. Many libertarian legal scholars have decried the creation of qualified immunity as an act of egregious judicial activism, noting that there is no basis in either the Constitution or congressional law for awarding public officials such a broad exemption from legal liability.

Of course, police organizations broadly oppose increasing cops’ exposure to civil suits. And this creates a substantial political obstacle to rolling back qualified immunity. But if reformers can create a climate in which the Supreme Court feels compelled to scale back the doctrine, or if they can elect a Congress and president willing to abolish it, once that single political victory is secured, power to pursue legal action against abusive cops will fall into the hands of actors over whom the police have little leverage — namely, the individuals they abuse and their attorneys.

In the long run, progressives must strive to build an America in which democratic institutions command more public esteem than lawless security forces. The exceptional popularity of the police, elected officials’ profound reliance on their faithful labors, and the prevalence of police misconduct are all inextricable from our government’s disinvestment from other public services. It is possible to live in a society where social-welfare institutions command greater reverence than the police ever have — just take a glance at how Britons view their National Health Service.

For the moment, though, reformers must recognize their adversaries’ political strength and continue finding creative ways of diminishing and sidestepping it.