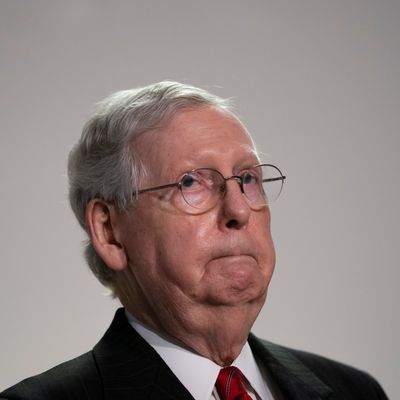

Mitch McConnell leads a political party that believes that Roe v. Wade legalized genocide, that Christian institutions have been placed under siege by LGBT extremists, and that most regulations of the corporate sector are stepping stones on the road to serfdom.

Whether these civic ills will turn fatal or dissipate depends largely on the composition of the Supreme Court. Conservatives have little hope of paring back reproductive freedom or restricting trans rights or repealing the Clean Air Act through congressional action. On the contrary, the party proved incapable of even partially repealing Barack Obama’s health-care law when it had unified control of Congress.

But federal judges don’t need to worry about alienating voters. And a conservative Supreme Court majority doesn’t need to get a bill through conference committee to kill the Affordable Care Act; it can do so by fiat. Thus, from the conservative perspective, nothing less than the cessation of mass murder, the maintenance of religious liberty, and the preemption of totalitarianism (and/or, social democracy) hinges on control of the high court.

In 2016, McConnell’s party controlled the Senate, which gave him the power to block Barack Obama’s proposed replacement for Antonin Scalia. Merrick Garland may have been a relatively moderate choice, but his ascension would nevertheless have cost conservatives’ their hard-won Supreme Court majority. Had Obama proposed a policy that the conservative movement vehemently opposed, no one would expect McConnell to support it. And yet, faced with a Supreme Court appointment that would undermine almost all of the conservative movement’s policy goals, Democrats indignantly demanded that the Senate majority leader put preserving “norms” above ending mass feticide. McConnell refused.

Four years later, McConnell’s party still controls the Senate. And now it has the White House too. This gives him the power to approve Donald Trump’s proposed replacement for Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg. The ascension of another right-wing jurist to the Court would advance almost all of the conservative movement’s ideological aims. And yet, Democrats are indignantly demanding that McConnell sit on his hands, and let the next president — who, according to polls, is very likely to be Joe Biden — handpick Ginsburg’s successor. McConnell has refused.

Framed in these terms, there is no contradiction between the Senate majority leader’s position on filling a Supreme Court seat in 2016 and his current one. And the rationale that unites them is also eminently reasonable: To confirm an Obama nominee, or block a Trump one, would be to grossly betray the causes that Mitch McConnell claims to stand for.

But McConnell did not make this argument.

Why everyone is pretending that the fight over Ginsburg’s replacement is actually about ethics in Senate proceduralism.

Instead, in 2016, he made an ideologically neutral argument about just procedure. “Given that we are in the midst of the presidential election process,” McConnell said, “we believe that the American people should seize the opportunity to weigh in on whom they trust to nominate the next person for a lifetime appointment to the Supreme Court.” A little over four years later — with voters already casting ballots in an election that is weeks away — McConnell has modified his view. Today, respect for popular sovereignty does not require holding a Supreme Court seat open for whichever candidate Americans elect in November. Rather, it requires Republicans to keep their “promise” to the Americans who “reelected our majority in 2016 and expanded it in 2018 because we pledged to work with President Trump and support his agenda, particularly his outstanding appointments to the federal judiciary.”

Democrats have (justifiably) cried hypocrisy. Although, their present position is in some tension with the one they held four years ago. Back then, Democrats insisted that whether a Supreme Court vacancy falls in an election year has no bearing on the sitting president’s right to appoint justices. Now, the party insists that although the rule McConnell articulated four years ago was misguided at the time it was established, the Senate majority leader must nevertheless respect his own precedent.

The resolution of this argument is likely to be tragic, but the debate itself is pure farce. On the campaign trail, Democrats and Republicans both invoke the enormous policy stakes of Supreme Court appointments, whether for abortion or LGBT rights or corporate influence over democracy. And yet, both sides then turn around and pretend that their support or opposition for a given Supreme Court nominee is rooted in some abstract principle with no inherent ideological valence.

The Democratic Party’s reasons for doing this are easier to understand (and their rationales, easier to defend). In both 2016 and 2020, Democrats had prevailing norms on their side, but not the prevailing balance of power. Traditionally, the Senate’s authority to advise and approve Supreme Court appointments was not construed as a right to block any and all nominees from an opposing party’s president. McConnell’s refusal to so much as grant Obama’s nominee a hearing was a gross violation of precedent, and one with threatening implications for an archaic constitutional order held together by norms of mutual restraint (given the frequency of divided government, an America where the same party must control the White House and Senate to replace dead Supreme Court justices is one in which the high court could be stuck at a 4-4 or 3-3 split for years on end). In this context, appeals to procedural fairness were the best ammunition at Democrats’ disposal. Making a forthright case for the substantive benefits of a liberal Supreme Court majority wouldn’t undermine McConnell’s position but justify it. Thus, Democrats tried to win over public opinion and moderate GOP Senators with the invocation of precedent. Four years later, the same basic dynamics are at work: Democrats lack the power to block the confirmation of Trump’s nominee, but they have a precedent (McConnell’s) to wield as a cudgel.

At first glance, the Senate majority leader’s appeals to procedural ethics are more puzzling. In the Supreme Court fights of 2016 and today, the actual reasons behind the GOP’s position are more coherent than their avowed ones. McConnell could have just said, “It is not reasonable to expect a Republican Senate to approve a Democratic president’s Supreme Court nominee, or to forgo an opportunity to approve a Republican president’s pick, given the enormous policy consequences of such actions.” But he didn’t.

McConnell’s motives aren’t actually indiscernible. One can deduce them by observing the Democrats’ growing chatter about court-packing: To frankly admit that the Supreme Court is a partisan, policy-making entity — and that its decisions are now of such profound ideological consequence that polarized parties can’t be expected to let norms constrain their attempts to gain judicial supremacy — would be to imperil the entire conservative judicial project.

The greatest trick conservative judicial activism ever pulled was convincing the world it doesn’t exist.

The American right’s agenda is unpopular. A majority of voters may support the Hyde Amendment, but they do not support the overturning of Roe v. Wade or the establishment of fetal personhood. Americans may be skeptical of “big government” as an abstract concept. But they like the Clean Air Act, and believe that Uncle Sam has a responsibility to ensure universal healthcare. And the conservative agenda is poised to grow more anti-majoritarian in the coming years, as the unprecedentedly left-wing millennial and zoomer generations reach their prime voting years.

In this context, the existence of a counter-majoritarian policy-making entity — that is broadly perceived as being above politics and which can advance conservative goals by declaring them constitutionally necessary (as opposed to having to persuade the public of their substantive merit) — is immensely valuable to the GOP. And this is all the more true now that Trump has packed the judiciary with Federalist Society 40-somethings. With a mere five conservative Supreme Court justices, Republicans have managed to ban limitations on corporate political spending, gut the Voting Rights Act, pare back Medicaid expansion, restrict the capacity of consumers and workers to sue corporations that abuse them, and stamp out school-desegregation efforts, among other things. Almost all these measures would have been too unpopular to enact through the (semi-) democratic branches of the U.S. government. And yet, the Roberts Court has not only assembled a record of conservative policy-making more far-reaching than Donald Trump’s — it has also managed to do so while retaining the approval of 56 percent of Democrats in Gallup’s most recent poll.

The fiction of an apolitical judiciary —whose judges harbor disparate constitutional philosophies but not loyalties to competing ideological projects — enables conservatives to enact much of their political agenda with little public awareness, let alone pushback. Each year, a select few Supreme Court cases become major news, while the vast majority pass by unnoticed by the median voter. This is an ideal setup for an anti-majoritarian ideological movement. And conservatives safeguard that setup by dutifully framing their judicial ambitions in ideologically neutral terms. So, McConnell did not justify blocking Obama’s 2016 Supreme Court nominee by noting Garland’s pro-labor jurisprudence would impede conservative economic goals. Rather, he appealed to popular sovereignty: Let the people decide who gets to pick the next justice. Similarly, in an editorial calling for Republicans to replace Ginsburg before Election Day, the National Review does not argue that fortifying a conservative Supreme Court majority is vital for advancing the right’s ideological aims, but rather, for advancing “constitutionalism on the Court” (as though there were one objective approach to applying the ambiguous language of an 18th-century document to 21st-century legal disputes, and that this entirely non-ideological approach just so happens to dictate conservative policy outcomes in virtually all cases).

If the McConnell rule is dead, then court-packing is permitted.

More fundamentally, maintaining the right’s capacity to implement anti-majoritarian policies from the bench requires maintaining a norm against the more democratic branches of government intervening in the judiciary’s affairs. Congress has the constitutional authority to alter the number of justices on the Supreme Court, and it has done so six times since the Republic’s inception. All that stands in the way of a Democratic president and Congress from legislating themselves a liberal Supreme Court majority are norms. And this is what’s actually at stake in the bizarre, mutually disingenuous procedural argument about election year Supreme Court appointments: McConnell wants to disguise the fact that he is subordinating norms of forbearance to the attainment of power, and Democrats want to expose this fact.

Of course, were a future Democratic government to violate the norm against Court expansion, they would clear the way for their Republican successors to do the same. But a world in which Supreme Court majorities come and go with shifts in partisan electoral fortunes would be much less favorable to conservatives than a world in which a six-member right-wing majority reigns for a generation. In the former case, the end result is likely to be the weakening (if not outright destruction) of judicial review — which is to say, of the judiciary’s power to declare duly enacted legislation unconstitutional. This is an authority that the Supreme Court gave itself in Marbury v. Madison and is nowhere to be found in the text of the Constitution. For the vast majority of U.S. history, judicial review has served as a tool of reaction, one that allowed conservative forces to insulate the prerogatives of economic elites from democratic challenge. If Republicans get their way, it will serve that same function in the decades to come.

McConnell’s flip-flop is the entire conservative legal project in miniature.

It’s hardly controversial to call McConnell’s present position on election-year Supreme Court appointments an attempt to disguise a will to power beneath a thin scrim of sophistry. What’s less widely accepted is that the conservative movement’s entire judicial project is more or less the same thing.

In his statement Friday, McConnell had the audacity to claim a popular mandate for approving another Trump justice. In the 2016 and 2018 elections, he argued, “Americans reelected” and expanded his majority, on the understanding that he would use it to confirm right-wing judges. Never mind that Americans cast fewer ballots for the Republican nominee than the Democratic one in 2016, or that they awarded Democrats a historic landslide in 2018’s House races, or that Senators serve six-year terms and thus a majority of Senate seats went uncontested in both of those elections.

The reality is that McConnell and Trump do not owe their power to popular assent but rather, to the Electoral College and the six-point, pro-Republican structural bias of a Senate that awards equal representation to the 578,000 (predominately white rural) residents of Wyoming and the 39.5 million (diverse, heavily urban) residents of California. That McConnell cited elections in which his party won fewer votes as evidence of a democratic mandate is absurd but telling. It is an expression of contempt for democracy disguised as an affirmation of that ideal. In this way, it deftly encapsulates the dissonance between the conservative movement’s official judicial philosophy and its actual one.

Officially, conservatives believe that the balance of judicial power should be determined democratically (hence McConnell’s repeated appeals to letting the people decide), and that the judiciary should refrain from “activism” or legislating from the bench, in deference to the democratically elected branches of government.

In actuality, the right’s position, plainly stated, is this: America’s anti-GOP majority has no preferences that Senate Republicans are bound to respect. The fact that a plurality of Americans rejected Donald Trump does not mean that he must show some deference to their views by nominating moderate justices to the Court. To the contrary, it is perfectly legitimate for the timing of various deaths — and the structural biases of America’s electoral institutions — to award conservatives with a far-right Supreme Court majority for decades to come, even as their party has lost the popular vote in six of seven presidential elections. What’s more, it is also legitimate for that majority to strike down the last Democratic president’s signature legislative achievement on specious grounds, or gut voting-rights legislation that Congress has recently authorized, or remove an entire categories of economic policy from the realm of democratic contestation — because legislating from the bench is only “judicial activism” when liberals do it; when we legislate from the bench, it is “constitutionalism.”

It is unclear whether Democrats have the spine to call this bluff. But someday (if we’re lucky, someday next year), they are going to have to decide whether to play by the rules McConnell advertises or those that actually govern his actions. Which is to say: The next time they secure the White House and a Senate majority, Democrats can either unilaterally defer to norms of forbearance, or they can use the full extent of their powers to reshape the judiciary to their ideological advantage. Adding justices to the Supreme Court would pose real hazards to our democracy. But so would allowing six unelected reactionaries in robes — five of whom owe their seats to presidents who entered office over plurality opposition — to stand athwart the Anthropocene yelling “Stop!” to climate action (or universal health care, or voting rights, or reproductive autonomy, etc.). At a time when an authoritarian right-wing movement is trying to consolidate power over the courts to implement the ideological agenda of a minority, there are worse things than destroying judicial review by turning the Supreme Court into an arm of elected governments. All else equal, it seems infinitely healthier for America to emulate the “parliamentary supremacy” of other Western democracies than the authoritarian clerisy of the Iranian republic.

For now, Democrats are begging McConnell to keep a fig leaf over his ruthless will to power. But once the conservative movement’s ambitions are fully exposed, Chuck Schumer & Co. should not avert their eyes. When judicial independence becomes an enemy of self-government, the former must give way to the latter. In a democratic republic, the emperors wear no robes.