With Wednesday’s second impeachment of Donald Trump, a second Senate trial for him is a certainty. But there is a lot of uncertainty remaining about when, exactly, the trial will convene, who will set it up, and who will preside over it.

McConnell has refused to bring the Senate back early to receive the article of impeachment passed by the House. So that means the earliest it could be “exhibited” by House impeachment managers in the Senate is January 19. If that happened expeditiously, a trial would begin at 1:00 p.m. on January 20 by the terms of the standing rules on impeachment trials. That’s an hour after Joe Biden and Kamala Harris are due to be sworn in at the inaugural ceremony.

The first question is who would be in a position to trigger the trial. If it were to happen right now it would be Mitch McConnell, since there are currently 51 Republican senators until Raphael Warnock is sworn in and replaces interim senator from Georgia Kelly Loeffler, and only 49 Democrats until Warnock and his new Georgia colleague, Jon Ossoff, are sworn in. Once that happens and Harris is sworn in as vice-president and president of the Senate, the chamber will flip to Democratic control and Chuck Schumer will be in charge of organizing the Senate generally and the impeachment trial specifically. But it’s unclear exactly when the Georgians will be certified by their state as winners of the January 5 runoff, and made eligible to take their seats. The deadline for state certification is January 22, but election officials have said it could happen a bit earlier, “around the same time as the January 20 inauguration.” It’s all a bit up in the air, and it’s still possible McConnell will draft and present ad hoc rules (procedures covering details not specified in the Constitution or the standing rules) under which Schumer will subsequently run the trial.

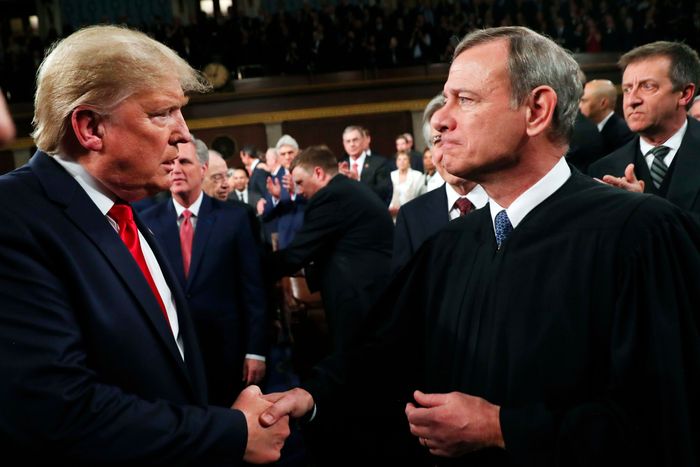

Aside from that ambivalent matter, there’s the question of who will be in the chair during the trial — the chair in which Chief Justice John Roberts sat in the first Trump trial. That depends on how one reads the language of the Constitution providing that “When the President of the United States is tried the Chief Justice shall preside.” If the trial begins after noon on Inauguration Day, the man symbolically in the dock will no longer be president. And it is reasonably clear that the Founders put the chief justice in the chair for a presidential impeachment trial because it would be unseemly for a vice-president who could be elevated to the presidency by a conviction to be in that position. That will not be the case if Trump is convicted though. So arguably Kamala Harris, not John Roberts, should preside; some even say incoming Democratic president pro tempore Pat Leahy might be a less controversial choice. (Trump, after all, called Harris a “monster” and a “communist” not long ago, in a prime example of his chronically impeachable character.) But some authorities think Roberts should still be in the chair, in part because Trump was president when the process began with impeachment by the House. And still others think either Roberts should decide whether to preside, or that the Senate can do whatever it wishes. There is scholarly support for all these positions and no real precedent.

This is more than a matter of ceremony. The person in the chair during an impeachment trial is in a position to make binding rulings on procedural objections and questions of constitutional law. In Trump’s second trial, a very big question of constitutional law will be whether (as many conservative legal wizards argue) the authority to hold an impeachment trial vanishes the moment its object is no longer in office. Without a doubt Trump’s defenders will make that argument, perhaps in a motion to dismiss the charges and end the trial. It could matter a great deal whether it’s Roberts ruling on that motion, which would virtually have the authority of a Supreme Court decision on an obscure topic never litigated in the federal courts; or it’s Harris or Leahy, who are very unlikely to put a halt to a trial that every single House Democrat deemed necessary in the impeachment vote.

Even so, Democrats might prefer that Roberts is presiding to give the proceedings a nonpartisan cast, knowing that if push came to shove they could override a ruling from the chair by majority vote. Most likely this and other trial details will be subject to negotiations involving both parties in the Senate along with House impeachment managers and possibly even Trump’s attorneys. If there is anything good about the lull between impeachment and trial, it’s that everyone will have the opportunity to absorb the unique details of his historic event and sort it out before Trump’s final contribution to chaos in Washington becomes the conduct of his own trial.