The Democratic House majority emerged from the 2020 election so bruised and emaciated that experts gave it less than three years to live.

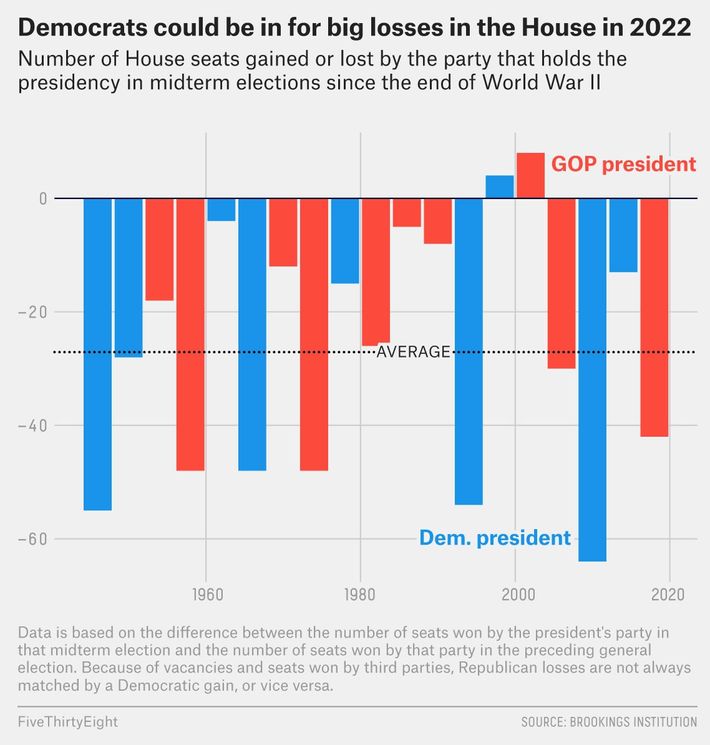

In defiance of polling and pundit expectations, Republicans netted 11 House seats in 2020, leaving Nancy Pelosi’s caucus perilously thin. Since World War II, the president’s party has lost an average of 27 House seats in midterm elections. If Democrats lose more than four in 2022, they will forfeit congressional control.

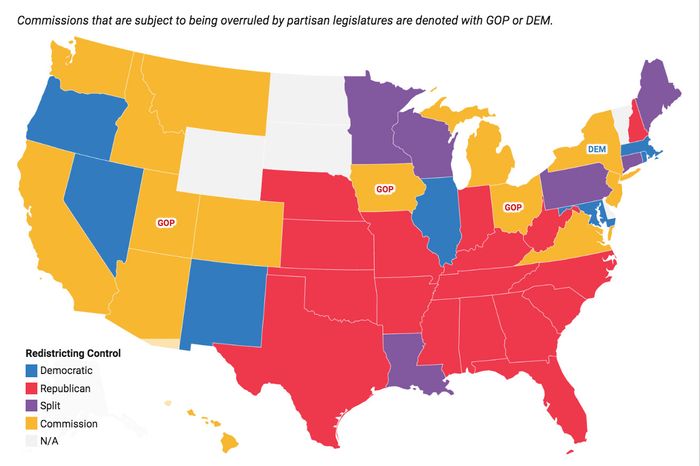

This outlook would be daunting enough by itself. But 2022 won’t just be the first midterm of Joe Biden’s presidency, it will also be the first federal election held after the House map is redrawn to fit the 2020 census. Republicans maintained their dominance of state governments in last year’s election and will therefore have more opportunities to gerrymander than Democrats will. GOP state governments have final authority over the drawing of 187 congressional districts, while Democrats have such authority over just 75. The existing House map was also the product of a Republican-dominated redistricting process in 2011. But between that year and 2018, suburbs across the nation unexpectedly drifted leftward, thereby breaking many GOP gerrymanders. Now, Republicans will have the opportunity to account for this error, and reshape the House map to the contours of their new coalition. What’s more, even without gerrymandering, Republican-leaning states would be poised to add seats from population shifts alone. All told, the GOP could gain as many as eight House seats in 2022, just from the redrawing of congressional maps, according to The Cook Political Report.

If the headwinds facing House Democrats have been clear since November, the preconditions for overcoming those headwinds have also been discernible: The party needed Joe Biden to stay popular, the Democratic base to stay mobilized — and, above all, for Congressional Democrats to level the playing field by banning partisan redistricting.

A little over 100 days into Biden’s presidency, Democrats are hitting only one of those three marks.

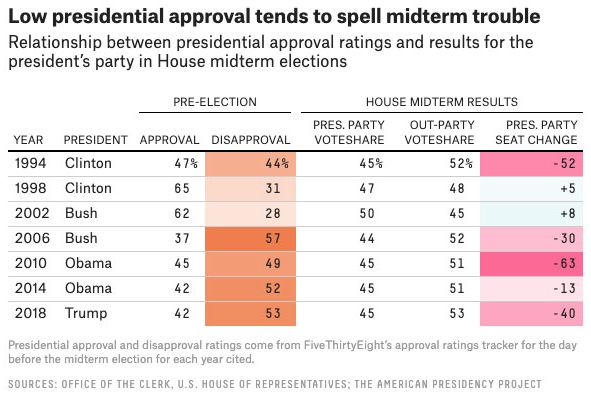

Historically, there’s been a strong correlation between the sitting president’s approval rating and his party’s midterm performance. Only twice in the last three decades has the president’s party gained seats in a midterm election; in both cases, their approval ratings exceeded 60 percent.

Biden’s favorability remains far below that threshold; as of this writing, FiveThirtyEight’s polling average has about 54 percent of Americans approving of the president and 41 percent disapproving. Nevertheless, if that polling average is roughly accurate — and Biden were to retain that level of support come November 2022 — then his party would have a fighting chance. That last if is a big one. Presidential approval almost always declines between the hundred-day mark and the midterm elections. Biden’s current favorability is robust in the abstract. But judged by the standards of presidential “honeymoon” periods, it’s relatively low: The only presidents who had lower approval ratings than Biden after 100 days in office were Gerald Ford and Donald Trump. Meanwhile, as David Shor notes, if one assumes that the Democratic Party’s popularity follows the average historical trajectory of an in-power party, then its current advantage in the House “generic ballot” would be too small to keep it from dipping below 50 percent by Election Day 2022.

Still, there are reasons to think that these historical benchmarks are obsolete. If partisan polarization has put a ceiling on Joe Biden’s support, it could also keep his solid-but-unspectacular approval rating steady going forward: The more firmly Americans are divided into separate partisan camps, the less likely emergent events are to change their allegiances. And there are other reasons to think Biden’s standing may hold up better than his predecessors’. Unlike many recent presidents, Biden is not pursuing any controversial legislative objectives. He is not trying to reform the U.S. healthcare system, or launch a ground invasion of a Middle Eastern country; he’s just trying to enact a bunch of popular infrastructure investments and social welfare programs, funded by popular tax hikes on the wealthy. Further, Biden appears poised to preside over the end of a pandemic, and the strongest economic growth that the U.S. has witnessed since 1984. By November 2022, America may well have the tightest labor market it’s seen since the late 1990s.

So Biden’s polling gives Democrats some cause for hope. Or it would, if Chuck Schumer’s caucus uniformly valued their own party’s political success over Senate tradition.

Earlier this year, the House passed a sweeping democracy reform package that included ambitious (though inadequate) restrictions on partisan gerrymandering. And there was some basis for hoping that this legislation would eventually make it through the Senate. Although Democrats only have a bare majority in the upper chamber — which is dependent on the cooperation of Joe Manchin, a conservative Democrat from one of America’s reddest states — they were able to get a $1.9 trillion COVID relief bill into law. Persuading Manchin and other moderate Democrats to abolish the legislative filibuster, so as to pass redistricting reform, was going to be a tall order. But it looked like Republicans were making the left’s task a bit easier: After a GOP president incited an insurrection on Capitol Hill — and Republicans passed a battery of voting restrictions in states across the country — surely moderate Democrats would recognize the high stakes of making federal representation more small-d democratic.

Alas, this hope turns out to have been misguided. In recent days, Manchin has made clear that he took a very different lesson from the January 6 than progressives did. As Vox’s Andrew Prokop reports:

Some filibuster reformers hope that, as the year goes on, the reality of Republican obstruction will become clear to Manchin and he’ll be driven to change his mind—that Senate rules will in the end be just as negotiable to him as the details of Biden’s stimulus bill. For instance, reformers hoped a GOP filibuster of Democrats’ big voting rights bill, the For the People Act, could spur holdout senators to change the rules to pass it, because it’s so important.

Manchin recoils at the very idea. “How in the world could you, with the tension we have right now, allow a voting bill to restructure the voting of America on a partisan line?” he asked. He says that 20 to 25% of the public already doesn’t trust the system and that a party-line overhaul would “guarantee” that number would increase, leading to more “anarchy” like that at the Capitol on January 6. He added: “I just believe with all my heart and soul that’s what would happen, and I’m not going to be part of it.”

Things could change in the coming weeks — and (small-d) democrats should do what they can to change them. But right now, federal redistricting reform looks dead. Senate Republicans aren’t going to vote for a law that directly costs their party House seats, and moderate Senate Democrats (apparently) won’t vote for one that gives their party a fighting chance at keeping Congress.

If redistricting reform does not happen, then Democrats will need a minor miracle to avert a GOP House takeover two years from now. Nothing short of the strongest midterm showing by any in-power party in modern American history will do. One can tell a story about how Democrats pull that off: As the pandemic recedes, America enters a historic economic boom, and the Democrats’ newfound strength with college-educated suburbanites (who reliably turnout for midterm elections) gives them the supper hand over a GOP increasingly reliant on rural, working-class voters (who’ve been disproportionately likely to sit out midterms).

On Saturday night, however, northern Texas put a dent in this dream.

The Lone Star State’s Sixth Congressional District has been in Republican hands since 1983. But as suburban voters in the Dallas–Fort Worth metro area have drifted left, the district has grown purple (or at least burgundy). In 2020, Trump won the area by just three points. So, Democrats hoped to see their party hold its own in the special House election there this weekend.

It didn’t.

The election was effectively a “jungle primary,” in which a large field of Republican and Democratic candidates competed to finish in either first or second place and thus, qualify for a decisive runoff election. Jana Lynne Sanchez, a communications professional who ran a strong campaign for the seat in 2018, was the Democrats’ favored candidate, and was widely expected to make the runoff. Instead, she came in third behind two Republicans, ensuring that the GOP will keep the seat. But that isn’t actually the most dispiriting aspect of the election for the Democratic Party. Were Saturday’s loss born of a mere coordination problem — with too many Democraitc candidates splitting the blue vote — then it would have few implications for the party’s 2022 outlook. But the main source of Sanchez’s woes was underwhelming Democratic turnout: The race’s GOP candidates collectively won 62 percent of the vote, while Democrats claimed just 37 percent. As Cal Jillson, a political scientist at Southern Methodist University, told the New York Times, “The Republicans turned out and the Democrats didn’t. That’s a critical takeaway.”

Special elections are special. Many idiosyncratic factors influence the outcomes of individual, off-year House elections. Republicans have held this north Texas seat for nearly forty years, and Democrats were unlikely to flip it with Biden in the White House, so Saturday’s election was always likely to function as a de-facto GOP primary. Given this reality, it’s unsurprising that Republican voters participated at a markedly higher rate. There’s no reason to presume that Democratic turnout will be as lackluster in the midterms as it was on Saturday.

If Democrats do not ban partisan gerrymandering, however, they won’t need strong turnout to keep the House in 2022 — they’ll need spectacular turnout to do so. And events in north Texas last weekend suggest that this scenario is as far-fetched as it sounds.

The Democratic Party will either use its tenuous grip on power to democratize House representation, or it will (almost certainly) surrender the chamber in 2023. Barring an epiphany on the other side of the Capitol, Nancy Pelosi should get ready to raise the white flag.