This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

Most of them don’t die. It’s easy to mistake the worst outcome for the most urgent crisis, but the reality is that the vast majority of people who have violent encounters with the police live to tell about it.

Meralyn Kirkland has been telling about it, and what it cost her family, since September 19, 2019 — when her manager pulled her aside and told her, sorry, there’s someone from your granddaughter’s school on the phone. It had been five years since she’d moved from the Bahamas into a 1,000-square-foot apartment in Orlando, Florida, and six years since Kaia Rolle, all eight gray-blue pounds of her, struggling to breathe, felt her grandmother stroke her shoulder and made her first “funny little squeak sound.” And it was eight months before George Floyd’s last breath knocked America on its back.

When Kirkland answered the phone that day, she was put on hold. “Hello,” said the man who finally picked up. “This is Officer Turner. I’m calling to tell you that Kaia’s been arrested. She’s on her way to the juvenile center.”

Kaia was an exuberant 6-year-old, the type who kept her grandparents on their toes but entertained. She struck up conversation with strangers everywhere, gave them hugs. They often joked that if Kirkland wasn’t careful, someone was going to “run away with her.” “I was trying to teach her the meaning of garrulous because that’s what she is,” says Kirkland. Kaia would turn their commutes into showcases for her singing. “She’d have the entire bus eating out of her hands.”

At age 4, Kaia began falling asleep at strange times — in the middle of sentences, during meals. Kirkland tells me there are photos of Kaia in her high chair with her mouth full of food and eyes shut. Her prekindergarten teachers said she would knock out during class as well, and her schoolwork was suffering because of it. Doctors couldn’t figure out what was wrong until one physician asked Kirkland about Kaia’s breathing and a light bulb flickered on. “I told the doctor how Kaia really snores,” says Kirkland, “and then in the middle of snoring, she would just cut out and I wouldn’t hear anything. And then she’d go into snorting, gasping, and she would start snoring again.” A sleep test confirmed that Kaia had pediatric obstructive sleep apnea.

When Kirkland dropped Kaia off at school the morning of September 19, she gave administrators a version of the same spiel she’d been giving them for weeks. There were side effects to Kaia’s condition: Sleep-deprived children can be irritable and prone to tantrums. And sure enough, within hours of arriving at school, Kaia started running with a pair of sunglasses that were part of a show-and-tell event. Her teacher chased her into another room. Kaia threw a tantrum — “screaming and rolling over and flailing her arms and legs,” says Kirkland. The teacher tried to restrain her — something else the doctors had said not to do and that Kirkland had relayed to the school. “She’ll scream, she’ll maybe run around, which is going to exhaust her more. And she’ll probably drop wherever she is and sleep.” At some point during the fracas, Kaia kicked her teacher — by accident, Kaia said later. Kirkland isn’t sure who summoned the officers who patrol the campus, or at what point Officer Dennis Turner entered the room, or exactly why he zip-tied Kaia’s hands behind her back and led her off school grounds. Body-camera footage of the incident, which was released in February 2020, shows the child begging her hulking captor to be freed. “Help me,” she sobs. “I don’t want to go to the police car. Please, please, please. Please let me go.”

Kirkland didn’t fully comprehend it at the time, but she and her granddaughter were in the introductory course of a sort of reeducation. She was an immigrant. Kaia was a child. Neither had interacted with the police in any meaningful way before that day. Neither had been given a concrete reason to be wary of law enforcement.

Kirkland could not have predicted that a similar civics lesson would grip the nation a few months later. Millions of Americans have spent the past year reassessing their relationship with their country through the prism of law enforcement, often inspired by teachers who did not set out to be teachers: Ahmaud Arbery in February 2020, hunted and gunned down in Georgia by vigilantes who were cozy with the police; Breonna Taylor in March, her home raided and her body riddled with police bullets in Kentucky; George Floyd in May, choked to death by police in Minnesota. Their lessons have been received at different frequencies and motivated different conclusions but point to a common understanding: The violence of American law enforcement degrades the lives of countless people, especially poor Black people, through its peculiar appetite for their death.

But that was still months away. When Kirkland picked Kaia up from the Juvenile Assessment Center, she was “shaking like a leaf” and repeating her grandmother’s phone number like an incantation. Her eyes were red from crying, and her wrists were abraded. Police cars don’t come with booster seats, so Kaia had been strapped into the back seat like an adult, with the restraints digging into her wrists every time the vehicle rounded a corner or stopped at a traffic light. “Grandma,” Kaia said when she saw Kirkland, “I told them to call you. I told them to call you.”

Kirkland was told that Kaia had been charged with simple battery. They said she would be rearrested if she didn’t show up for court. One of the women who worked at the center was crying. A special step stool had to be brought in for Kaia’s mug shot. The same regretful sentiment united the people who had facilitated the event: the workers who processed Kaia at the center, Officer Turner’s partner, the police chief who eventually fired Officer Turner for not seeking his approval before the arrest, and the prosecutor who, the following Monday, dropped the charges. All felt Kaia’s arrest was a travesty and should never have happened. And yet, while it was happening, nobody stepped forward to stop it.

When Kirkland later tried enrolling Kaia in a different public school, her enthusiasm for a return to familiar routine died at the curb. As Kirkland pulled up to campus, Kaia saw a police car parked out front and reacted as though she had just seen an unusually sadistic bully. “She was crying and screaming and got down on the floor,” Kirkland says. “I’m like, ‘Kaia, what’s going on? You wanted to go to school.’ She’s like, ‘No, no, the officer was waiting for me.’ ” It had been months since she’d been inside a classroom, and she was often afraid to leave her grandmother’s side. Sirens started to make her skittish, afraid she was being pursued. She had night terrors and wet the bed. When she saw a cousin who worked as a correction officer in his uniform at a family gathering, she “started to go ballistic.”

Eventually, Kaia was diagnosed with post-traumatic-stress disorder and started seeing a therapist. “The therapist is showing her videos of police playing ball with kids, rescuing kittens from trees, pushing kids on bikes,” says Kirkland. The idea they are trying to convey to Kaia is “that a uniformed police officer does not need to be associated with fear or bad emotions,” Kirkland explains. “They can be your friend.”

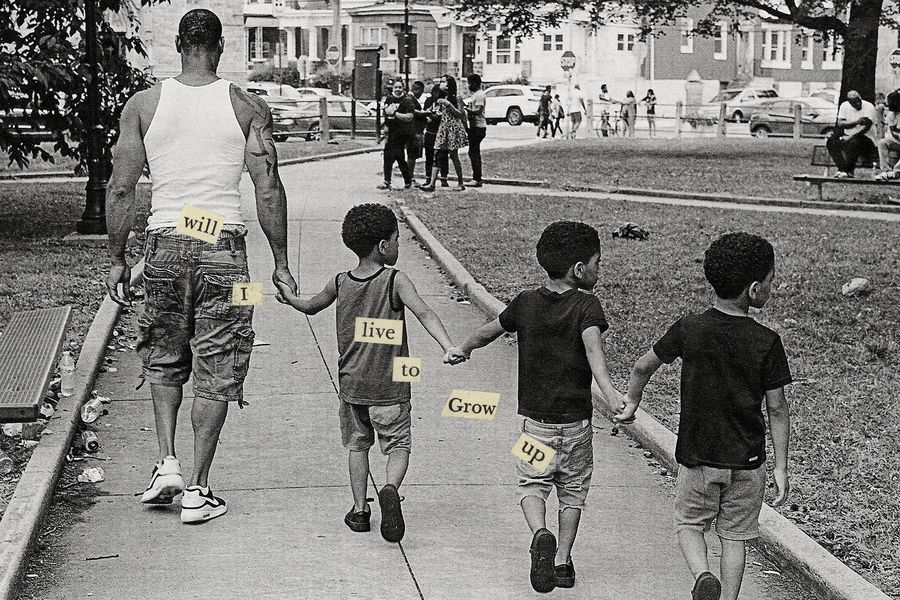

The real concern is not Kaia’s reintegration into schools. It’s how her fear of the police manifests “15 years from now — she could have an encounter with a police officer that triggers her.” Kirkland has seen the videos of police slayings flooding social media in recent years. “The police could pull her over for running a STOP sign. And it could cause her to speed off or something that could cause her to be shot.”

The therapist is reprogramming Kaia to associate the police with a belief that she can “trust them,” despite her hard-earned knowledge to the contrary. If adult Kaia is stopped by the police and doesn’t get shot, perhaps she’ll be considered a success story.

But we have seen the bodies go limp. We have heard the tear-gas canisters clatter and hiss. We have felt the batons, the tightening zip ties, heard the officers spit back “Blue lives matter” and watched them fly their blue-line flag over dead bodies. And even as the police brutalize us and wave off our pleas for justice and accountability, we have also seen them attempt to recuperate. Now they’re here to tell us they can be accountable. We’ll do better — just give us more money. Revamped training will fix us. New multimillion-dollar facilities will chasten us and teach us that we can’t just pillage your bodies and homes. They want us to forget that nagging sense some of us started to get last summer — that maybe, just maybe, these armed authoritarians aren’t the inevitability they want us to believe they are.

Last spring and summer probably would not have unfolded with such ferocity had most of us not been stuck indoors and isolated from the faces and places that gave our lives their familiar texture, watching a lot of people die.

In January 2020, a virus snaked past China’s borders, fulfilling its deadly purpose with special enthusiasm in the bodies of the elderly — those conduits to our sense of origin, the people who anchor us in history. The younger among us soon understood that our bodies could become weapons, capable of exterminating entire generations of our families, so we hid from one another and from them.

You didn’t have to be clairvoyant to predict where the fallout from this pandemic would land most heavily. The ranks of the newly dead swelled with the Black poor of Milwaukee, Detroit, and New Orleans, while the lines outside food banks stretched for miles through Latino sections of Texas and Southern California, where service and hospitality workers found themselves suddenly out of a job. All the while, our feckless president insisted that the losses mounting around us were a mirage, that the coronavirus was no more serious than a flu.

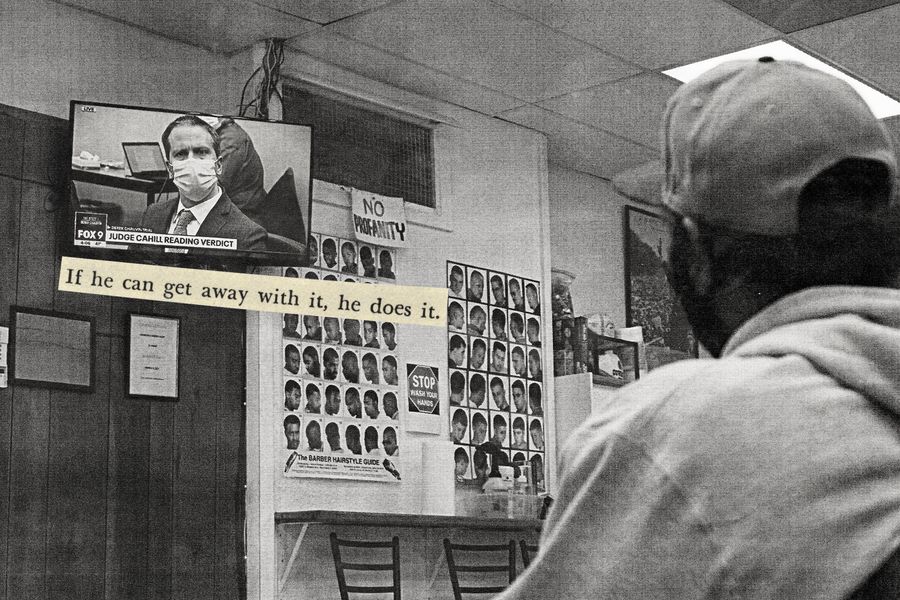

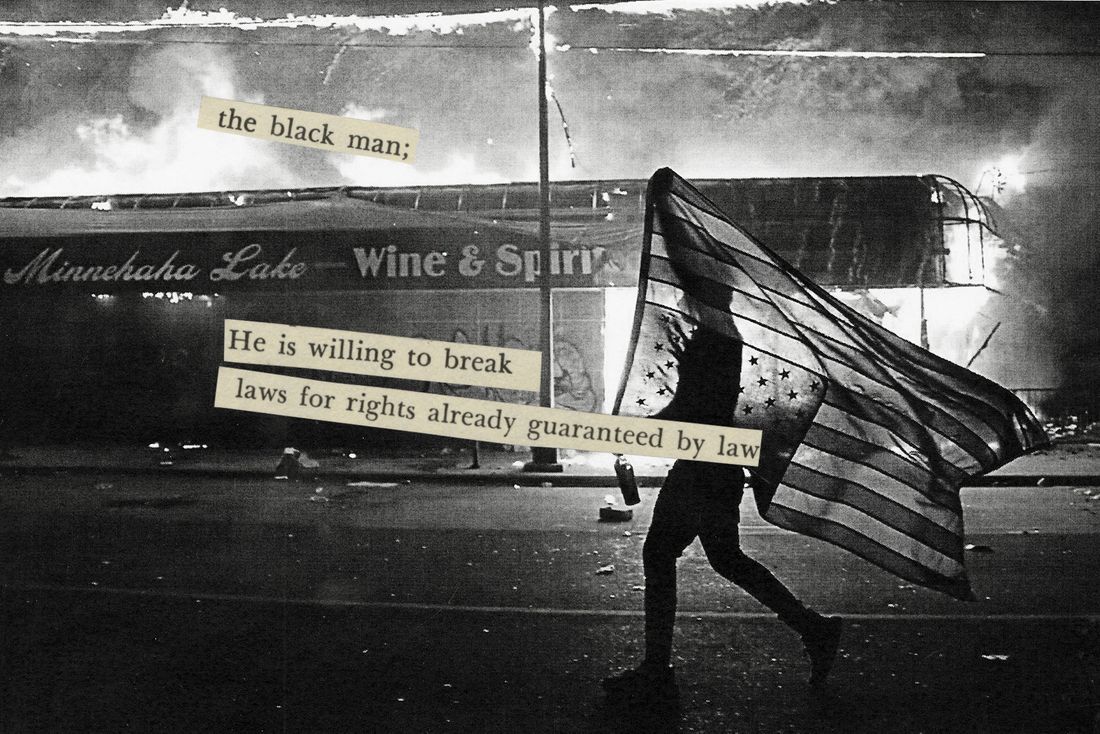

Maybe we were naïve to be so outraged that this state of cataclysm and deception did not stop the police from being the police. Of course, the carousel of Black death that carried us through the end of the Obama years would come back around — this time, in fact, in even more vivid cinematographic detail. Ahmaud Arbery was the fuel, but Minneapolis was the spark. From inside our bunkers and behind our screens, we watched Derek Chauvin kneel on George Floyd’s neck for nearly nine agonizing minutes. People began trickling, then flooding, into the streets, and before long we were in the midst of a full-blown revolt.

I suspect that much of it was because we were sick of all the dying. The news found Meralyn Kirkland at home, washing over her in waves of blue light. She stayed awake for hours watching a nation’s wrath. There seemed to be no reprieve from it. Floyd, handcuffed on his stomach, gasping “I can’t breathe,” reminded her of “the heavyset gentleman who the police also killed in front of a store — I think it was in New York”: Eric Garner. News but no images of Breonna Taylor’s killing. Kirkland could only imagine her last moments, the terror that must have seized the poor girl. The streets were filled with people, the air with smoke and sirens. “I was outraged,” Kirkland says.

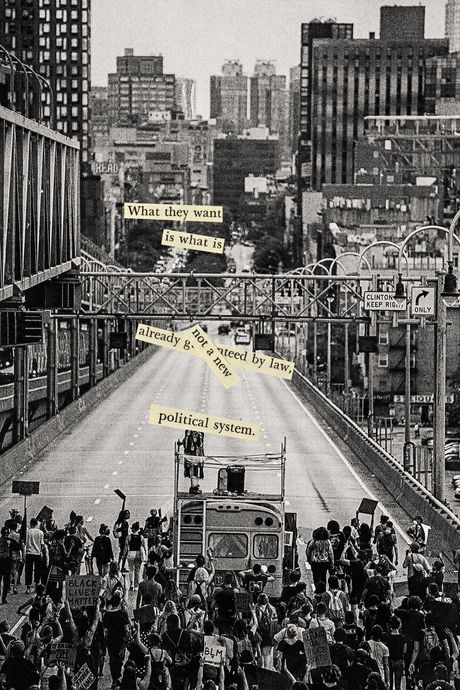

Those days of fire would subside as elected officials promised to reform, and some to reimagine, the agencies that had been licensed to kill us. But a renewed authoritarian fervor gripped others. Senator Tom Cotton published a New York Times editorial calling for the military to be dispatched to cities that had experienced rioting. President Trump deployed federal agents to Portland, Oregon. Protests surged. It became easy, in those days, to observe Trump’s ability to rouse popular fury and attribute much of the crisis to his presence. The tantalizing possibility of his ouster from the White House divided us. Some onlookers saw the destructive outcry inspired by Floyd’s death as a boon to his reelection campaign that November and shamed the rioters for being self-defeating. It seemed not to occur to them that electoralism was not the uprising’s main area of concern — nor was the median voter its target audience.

The truth was that voters already faced a more nefarious threat. While the police were gassing us in the streets and gunning eyes out with rubber bullets, the GOP — which at the time controlled the presidency, the U.S. Senate, most state legislatures and governorships, and the U.S. Supreme Court in all but name — was continuing its yearslong campaign to convince its base that the bulk of Democratic votes was fraudulent. When Trump lost, thousands of its supporters stormed the U.S. Capitol and began tearing it apart from the inside: an insurrection orchestrated by the state, not against it. And Republicans the nation over have spent the intervening months trying to sustain its energy — often empowering the police and, in many ways, insulating them from the public sentiment mounting against them.

Last year’s outcry, in all its dizzying complexity, marked an American rebellion of unusual scope and intensity that coincided with a confluence of social factors that might never be replicated again. But one year later, even early signs of progress have begun to acquire a sour taste — a federal police-reform bill, now stalled amid partisan disagreement; a wave of cities whose commitment to slashing police budgets fell far short of their rhetoric. Minneapolis public schools severed their relationship with the city’s police department the month after Floyd’s murder — only to replace it with a cadre of “public safety support specialists,” more than half of whom are former police, security, or correction officers.

What, if anything, it will change about everyday policing in the United States is far from apparent. Last year’s fire, and the sense of catastrophe that fed it, was not isolated to that uniquely combustible moment — the pandemic that fueled it, the economic crisis that shaped it, the reviled president who oversaw it — but a constant state of emergency. In recent months, some officials have become more enthusiastic about denouncing death at the hands of law enforcement. We will be tempted, as time passes, to relent and embrace the seeming wisdom of reflexive moderation — even though the reforms they’ve offered will stop neither the killings nor the quieter forms of violence the police inflict. Even what is arguably the farthest-reaching provision of the federal George Floyd Justice in Policing Act — which would end qualified immunity and its protection of officers from civil liability for wrongdoing — is akin to a fire-insurance payout after one’s house has already been burned to ashes.

We can choose to be sated by more cops in jail, by the cathartic promise of trials and convictions and the suggestion that this system can self-regulate. Or we can insist that bargaining for mere survival is not enough.

On July 6 of last year, the lawyer and organizer Derecka Purnell published an essay in The Atlantic that offered a provocative hypothetical: “What if Derek Chauvin had kneeled on George Floyd’s neck for seven minutes and 46 seconds instead of eight?” The unifying theme of the riots that gripped Minneapolis and sent its 3rd Police Precinct, and dozens of other cities, up in flames was death, typically video-recorded and made available for public consumption. But fewer people seemed to believe that policing that didn’t end fatally was also a catastrophe. “Police violence transcends so much more than killing,” Purnell says. “You know? It makes me so sad to know that George Floyd’s life still could have been ruined by this encounter over a $20 bill.”

For survivors, there is still incarceration, work lost, crushing financial commitments to courts and the state, families fractured. There are children, like Kaia, whose nascent sense of safety is decimated before it can take shape, and who are being taught a social contract in which desperation and illness are met with draconian punishment. “That’s something I think about a lot,” says Tiffany Roberts, a former public defender who now works for the Southern Center for Human Rights in Atlanta. “What about the ones who don’t die?’”

In Orlando, the incident at Kaia Rolle’s school was followed by what, in relative terms, seemed like swift and appropriate reprisal: The criminal charges against her were dropped, her record was expunged, and the officer who detained her was fired. Within three weeks, state legislators had reached out to the family. They wanted to attach Kaia’s name to a bill that would mostly prohibit the arrest of children under the age of 10.

In March 2020, Kaia and Meralyn Kirkland and several members of their family drove four hours to the state capitol. “They had this big billboard made with her picture and everything,” says Kirkland. But the Senate never got around to the proposal, leaving the House to pass a moderate amendment to a larger safety bill. It still bore the child’s name: the Kaia Rolle Act. A standing ovation greeted the family, but it was clear that the procedures the new legislation required weren’t that different from the rules Officer Turner had already broken.

In the meantime, Kirkland was paying for what had happened to her granddaughter in unexpected ways. She had secured a scholarship for Kaia to attend a new private school but still had to come up with almost $3,000 a year to cover the difference. Kirkland was older and had diabetes, so her job at the bank had allowed her to start working from home during COVID, but then Kaia’s school closed, too. Kaia was on medication to deal with her PTSD and was still having nightmares. More family members moved in to help, including Kaia’s mother, whose immigration status had kept her in the Bahamas for long stretches. But the apartment was too small to accommodate all of them, and the car too rickety, so Kirkland had to invest in new versions of both.

Kirkland burned through her meager 401(k) to keep up with expenses. “The police get on TV, apologize; the state attorney goes on TV and apologizes,” she says. “Everybody was genuinely sorry, but nobody cared about what happened to Kaia after they apologized.”

This larger recognition, that these costs keep accumulating in the lives of individuals and their communities, led Purnell to a discipline that aims “to eradicate the spectacular but also the mundane forms of violence that come with police and prisons.” She became an abolitionist, somebody who seeks to get rid of the police altogether. After Ferguson in 2014 — Michael Brown’s body left for hours on the blacktop like a warning; the humiliating announcement that former officer Darren Wilson would not be charged — “most of the chants were ‘Indict,’ ” says Purnell. “It was so much about locking up the cops and seeing the criminal-legal system as, like, That’s where we get our justice.”

The folly of calling on the police to police themselves has become clearer by the day. The nationwide rate of police killings has not slowed in the seven years since. For all the federal investigations into discriminatory patterns, for all the proposed reforms — body cameras, a renewed emphasis on “community policing,” an uptick in the share of officers indicted — law enforcement remains, as ever, an institution whose duty is to enforce order through the threat or application of violence. The response by elected leaders, offered as a frantic rejoinder to last summer’s uprising, assumes that Americans cannot see this — that we have forgotten. The Democrats’ federal policing bill is currently a litany of provisions that were already in place in many of the departments whose bad behavior prompted the demonstrations to begin with. “What we’re saying is that, ‘Well, we’re okay with the police being violent,’ ” says Purnell. “ ‘Just don’t kill anybody.’ ”

Last June in Georgia, where I live, Atlanta mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms admitted that moderate reforms like de-escalation training and requiring officers to intervene to stop abusive colleagues had failed — and then proposed the same measures in response to Rayshard Brooks’s killing at a local Wendy’s on June 12. When Officer Garrett Rolfe, who killed Brooks, was fired and charged with murder, police across the city called out sick in protest, leaving entire precincts unmanned. Within a year, the mayor had rewarded their abdication of duty with a pay bonus.

Reformist fervor has stalled elsewhere, too. Despite the plaudits (and ridicule) that greeted some cities’ proclamations that they would defund or disband their police departments, the reality has been nearly as underwhelming as Atlanta’s. Minneapolis found its city council’s effort to disband the police overturned by an old charter, preventing the proposal from getting on the November ballot. Last summer, Austin made headlines for promising to cut its police budget by one-third. The actual reduction looks closer to 5 percent, and even less if new cadet classes get the funding that some councilmembers and the mayor are lobbying to reinstate. As several cities experience upticks in violence — the exact causes of which remain undetermined — the long-accepted notion that more policing means more safety is eclipsing the gains set in motion by last year’s protests. “It is so ingrained that you’re only safe if you’re rounding up as many Black folks as possible,” says Roberts.

The idea of abolition has caught on with a growing minority of Americans, and it became one of the proposals most associated with the past year’s outcry, because it promises what reform cannot: an actual end to police violence and a commitment to the investments — in education and health care and housing — that would, theoretically, supplant the supposed need for agents with guns roaming the streets.

It is not a new discipline. The modern movement to get rid of the police and prisons gained steam in the 1990s, when scholar-activists Angela Davis and Ruth Wilson Gilmore built its tenets into campaigns to decelerate California’s prison-building boom. Its more recent adoption by dissidents speaks, in large part, to a recognition that the rot at the core of American policing transcends the conduct of individuals. Some people have deployed its terminology, misleadingly, to call for more reforms. But longtime abolitionists and their growing ranks insist they mean what they say. Purnell imagines that “over time, as these things become more popular, the same thing is going to happen with the current abolitionist movement that did with the slavery-abolitionist movement.”

The kind of mass mobilization that might enable such an endeavor, or any meaningful political action, for that matter, is precisely the sort of power shift the police and lawmakers are rallying to keep at bay. On April 19, Sheriff Grady Judd of Polk County, Florida, held up a photo of Disney World to a group of reporters and lawmakers gathered at the state capitol. “We’re a special place, and there are millions and millions of people who like to come here,” he said of his home state. “And quite frankly, we like to have them here.” Then he issued a warning to those seeking to relocate. “Welcome to Florida. But don’t register to vote and vote the stupid way you did up North; you’ll get what they got.”

What they got up North, in Judd’s view, was mobocracy. Judd had no patience for the way Yankee pols indulged the criminals who, he claimed, ruled the streets. This was a man whose deputies cornered a guy they suspected of killing an officer in 2006 and shot him 68 times. “That’s all the bullets we had, or we would have shot him more,” he said. All that chaos in Democrat country, Judd reckoned, was a consequence of voting — the wrong people doing it, and choosing the wrong leaders because of it. The answer was to restrict these people’s capacity to cast ballots at all. The men standing around Judd were well on their way to doing so.

This was at the signing ceremony for House Bill 1, the Florida “anti-rioting” bill. The legislation is a marvel of anti-democratic sentiment, albeit milder than Governor Ron DeSantis’s original proposal. As first conceived, the bill would have granted immunity to people who ran over protesters with their cars. Now it just grants those motorists special protections if they get sued in civil court. In another iteration of this long-gestating crackdown, after Floridians voted overwhelmingly to restore voting rights to formerly convicted people in 2018, the newly elected DeSantis implemented a de facto poll tax, requiring those would-be voters, a disproportionate share of them Black, to pay all outstanding fines and fees before registering. On May 6, DeSantis signed Senate Bill 90, an analog to the restrictive voting laws passed around the same time in Georgia, Montana, and Iowa. The bill limits the use of mail-in ballots and drop boxes and imposes tougher restrictions on the type of ID needed to request them, all measures designed to suppress votes cast by Black and poor people.

Lest rogue impulses be ascribed to the Sunshine State, note that these developments supplement a national scheme. Experts predict that the structural bias against Democrats in U.S. Senate elections will be all but insurmountable in coming elections — that is, if we’re still holding elections as they are now understood.

The franchise is being smothered. Open season on protesters has been declared with an eye toward fortifying the assault on equal representation happening at every level of national government. All of this is being implemented in concert with the enrichment and empowerment of the police. DeSantis’s anti-riot law punishes municipalities for slashing their law-enforcement budgets. Officers and reactionary lawmakers stand shoulder to shoulder at public ceremonies where their ambitions to gut democracy, to run roughshod over people’s ability to choose their leaders, are no longer the stuff of subtext but of open proclamation.

“The sober analysis is they’re winning,” says Phillip Agnew, co-founder of the activist organization Dream Defenders, “because they’re cheating, and when they get there, they’re doing everything they can to stay in power.” These newly flush police, whom we will not be allowed to defund or otherwise disempower, will be charged with punishing our disaffection. American law enforcement will have eclipsed democracy before we realize our capacity to prevent it.

The solution that Agnew tries to sell to members of his newer group, Black Men Build, is better organization. What he describes, specifically, sounds like a mass strike — once an essential part of the arsenal wielded by labor unions to offset capitalist power, but rarer after years of legislative assault that reduced them, in many states, to nonentities. Enacted strategically, such a strike might shut down large swaths of the country. At least that’s the idea. “I don’t want to say too much,” he says, “but if they know that doing something like [these laws] means that the ports are going to be closed, that the amusement parks are not going to operate, that tourism is going to be affected, that the tollways aren’t going to work — that’s the level that we need to get on that we’re not on. Do you know what I mean? We haven’t organized ourselves to be a disruptive enough force.”

This past March of 2021, Kirkland and Kaia got a call. Modified provisions of the original Kaia Rolle Act were expected to pass both chambers of the legislature with bipartisan support as part of a bigger policing-reform bill inspired by the George Floyd uprisings. They made the trip to Tallahassee again. Kirkland and Rolle looked on as lawmakers celebrated a chilling compromise: Except in the case of a “forcible felony,” it was now prohibited for police officers to arrest children under the age of 7. The sentiment that had clinched its unanimous passage — that what happened to Kaia was unacceptable — apparently did not extend past the second grade.

The bill is languishing on Governor DeSantis’s desk, still unsigned. Kaia has bad days and better days, grades that go up and down, periodic meltdowns, fits of anxiety. Her hope for recuperation bound up in the passage of time and a propagandistic cartoon cop rescuing a kitten from a tree.

Over the past year, we have seen death transmuted into rebellion, only to be sublimated into reforms that reproduce the same violence. The police have even dangled catharsis. In a Minneapolis courtroom last month, Derek Chauvin was convicted on the strength of his fellow officers’ testimony, an attempt to prove the value of the prisons they typically reserve for us. Before the verdict was even read, they started killing again. Daunte Wright of Brooklyn Center, Minnesota, was still slumped over the steering wheel of his car, bleeding out, when the police department whose officer shot him flew a flag bisected by a thin blue line. After the killing of Ma’Khia Bryant in Columbus, Ohio, an officer was filmed retorting “Blue lives matter” to grieving onlookers.

Last year, many of us recognized that the rate at which the police kill is a catastrophe. Next time, maybe we realize that the more fundamental catastrophe is them.