Guy Velella was the kind of colorful politician who represents a different era in New York City. A Bronx Republican state senator from 1986 to 2004, he led the borough’s Republican Party as it slid into irrelevance, failing to back Rudy Giuliani or Mike Bloomberg in their mayoral runs. The married father of four kept an “Albany wife,” as the saying used to go, had an out-of-wedlock daughter with her, and steered a $24,000 pension payment to his mistress’s mother. After a career marked by ethical lapses, he was sent to Rikers Island in 2004 for accepting bribes but was released a few months later after an obscure panel packed with political appointees recommended he and his cronies be let go, saying they seemed “distraught.”

Velella died in 2011, but his legacy lives on at the city’s Board of Elections, where Dawn Sandow, a longtime Velella aide, is the de facto executive director; the actual executive director, Michael Ryan, has been on a monthslong medical leave. Sandow, entrusted with administering the city’s first ranked-choice-vote election (and its promise of forward-thinking democratic elections), was probed by the Department of Investigation in 2007 for not actually living in the Bronx and for doing campaign work on government time. Still, people familiar with the BOE’s inner workings describe her as one of the more capable employees at an agency that has long been a swamp of incompetence and patronage. “People come to you, tell you they need a job, and you send them to the BOE,” one city councilman told me. “It’s a cesspool.”

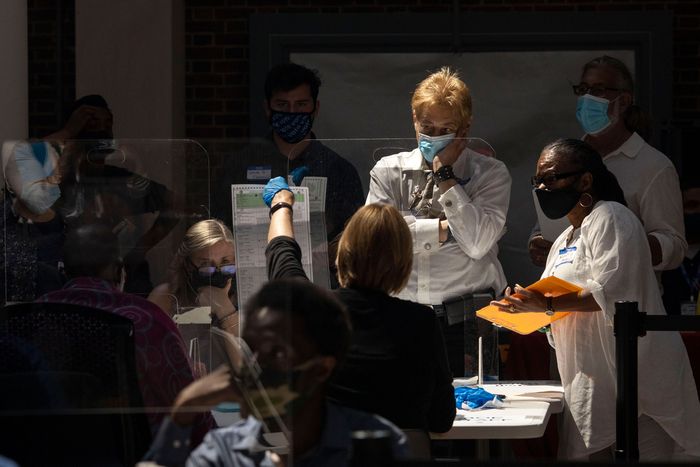

The BOE’s job is to administer city elections and maintain voter registrations, records, and rolls. The board isn’t even the referee; its members are simply the people who change the numbers on the scoreboard. But this year, the BOE posted the wrong score on the jumbotron. A week after Election Day, the board announced a preliminary tally of the results. They showed that in the 11th round of ranked-choice voting, whereby the person with the lowest number of votes is eliminated and their votes redistributed, former Sanitation Department head Kathryn Garcia had surged to second place, trailing former Brooklyn Borough President Eric Adams by only two points with more than 124,000 absentee ballots still outstanding. Maya Wiley was close behind. Suddenly, the unlikely prospect of a Mayor Garcia or a Mayor Wiley looked a lot more plausible. The tally also showed that turnout was much higher than originally calculated. Adams, who has for months been questioning ranked-choice voting — his allies sued to stop it from being implemented, and he invoked Jim Crow when describing Garcia and Andrew Yang’s campaigning together, a common practice in such races — cried foul.

“The vote total just released by the Board of Elections is 100,000-plus more than the total announced on election night, raising serious questions,” Adams’s statement released that night read. “We have asked the Board of Elections to explain such a massive increase and other irregularities.” There have been fears throughout the campaign that Adams would refuse to accept the results of the election — Yang got him on the record about it at one of the debates — and it seemed like we were facing a municipal moment with our very own Donald Trump.

But it turns out that Adams was right. The BOE, in a turn of events that defies human reason, had accidentally included more than 130,000 “test ballots” in its count. (“Wouldn’t it make sense,” tweeted NY1’s Errol Louis, “to plug in the names of the 7 Dwarves or Santa’s reindeer or something for the test run,” rather than real candidate names?) Updates came slowly through social media. Eventually, the agency released a statement blaming “human error” before taking the results page down and announcing that it was going to run the tallies again, this time with the dummy ballots removed.

And so for a sticky 24 hours, as phones buzzed with warnings of a blackout, political operatives texted reporters who texted other political operatives, all with the same question: What are you hearing? The answer was nothing. First the BOE was going to release the results at 2 p.m., then between two and three, then sometime that day, then possibly in the first week of July.

Somehow the lights in the city stayed on, the heat broke, and the board released the results, which showed much of what the previously announced results had: Adams up barely over Garcia, and Garcia up by just a few hundred votes over Wiley.

But the stench of bureaucratic error is likely to remain, threatening voters’ trust in the process. In this high-profile election, the progressive promise of ranked-choice voting was clashing with the realities of a creaky system. While BOE officials insisted that their goof had nothing to do with ranked-choice voting, they surely wouldn’t have been running simulations without it.

“The structure of the Board of Election is not conducive to efficiency in terms of its personnel and hiring, and that translated into a less-than-optimal work performance by the staff,” said Douglas Kellner, a former BOE commissioner who is the current co-chair of the State Board of Elections and someone who has a remarkable talent for deadpan understatement.

The BOE is one of the last vestiges of the old machinery in New York; each borough party gets to appoint two commissioners, who are then in charge of hiring staff. If you are wondering how, say, the Bronx — where Republicans make up just 3 percent of the population — could find an office’s worth of qualified Republican staffers … well. (Related: Why would someone get involved in the Bronx Republican Party, a political organization that post-Velella has almost no chance of ever winning local elections again?) Or consider that the person in charge of voter registration at the board is Beth Fossella, the octogenarian mother of Vito Fossella, who was the congressman from Staten Island until it was discovered that he kept a second family in the suburbs of Virginia and decided he would not seek reelection. (Fossella mounted a comeback this year by running for Staten Island borough president; he barely campaigned but currently leads by 200 votes.)

Now that the question of initial tallies has been resolved, it seems likely that we are heading into a long, hot summer of lawsuits and recriminations. The Garcia, Wiley, and Adams campaigns have already lawyered up. In the days after the polls closed on June 22, Adams very much acted like the next mayor of New York City, holding press conferences and declaring himself “the face of the new Democratic Party,” while a thousand takes bloomed about how his tough-on-crime messaging beat out the calls to defund the police. Adams’s rivals seemed content to let him have the microphone; the votes still needed to be counted. Wiley went to Fire Island. Garcia went upstate with her family and made some overdue repairs to her Park Slope home.

The Adams campaign has remained confident that once the absentee votes are counted, Adams will be declared the winner. His rivals suspect that part of the reason he spent the days after the election acting like a mayor-in-waiting was to lay the groundwork for a claim that the election was stolen from him should Garcia (or, less likely, Wiley) somehow beat him in the absentees and set himself up as a foil to the eventual winner, much as Giuliani spent the years after his first run for the mayoralty as a counterpoint to the man who defeated him, David Dinkins.

It is possible that old-school incompetence could revive efforts to repeal ranked-choice voting, and something that has been a decade-long priority for reformers won’t survive 2021, especially if it vaults the person who came in third on Election Night into City Hall and the person who came in first says he was robbed.

Susan Lerner, the head of Common Cause New York, who had pushed for the law, told me she was confident ranked-choice voting would survive.

“The voters like it. And the typical voter isn’t sitting at home, waiting for intermediate results. This delay was a problem for the press and the candidates and the campaigns. Most voters just want democracy to work.”

More on the NYC Mayoral Race

- Free the Trump Trial Transcripts

- On Patrol With the New York City Rat Czar

- Earthquake and Aftershock Shake New York City: Live Updates