The World Health Organization approved on Wednesday the first-ever vaccine preventing the transmission of malaria, the mosquito-borne virus that kills an estimated 500,000 people every year, including around 260,000 children under the age of 5. The green-light is a major step toward the widespread distribution of the vaccine to regions struck by malaria, including sub-Saharan Africa, where the majority of malaria deaths occur. Dr. Pedro Alonso, director of the WHO’s global malaria program, called the development of a vaccine against a disease that killed hundreds of millions in the 20th century alone a “historic event.”

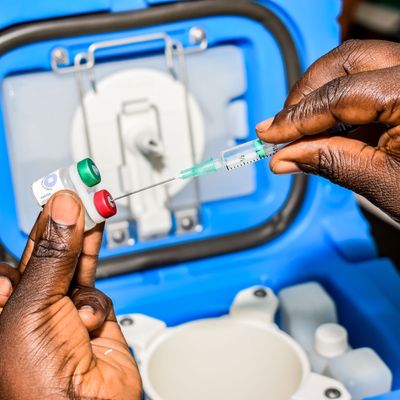

The Mosquirix shot, which has been in the works for over 30 years, creates antibodies to combat Plasmodium falciparum, the most dangerous of the five malaria pathogens and the most commonly found strain in sub-Saharan Africa. It is also the first-ever vaccine approved for a parasitic disease; most vaccines protect people against viruses, which are much simpler to combat with inoculations. Mosquirix is designed to be administered in three doses to infants between 5 and 17 months, with a fourth shot around 18 months later.

While this represents progress in the effort to stop one of the deadliest diseases in human history, the vaccine is not as effective as the coronavirus shots approved for use by the World Health Organization late last year. Clinical trials showed that the vaccine had an efficacy rate of about 50 percent against severe malaria in the first year after inoculation; that percentage dropped to almost zero by year four. Clinical trials also didn’t measure to what extent the shot directly prevented death, though Dr. Mary Hamel, the head of the WHO’s malaria-vaccine implementation program, told the New York Times that severe malaria functions as a “reliable proximal indicator of mortality.” And one modeling study from last year found that if the shots were distributed to countries most severely affected by malaria — which include Nigeria, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Tanzania, Burkina Faso, Mozambique, and Niger — as many as 5.4 million cases and 23,000 deaths in children under 5 could be prevented annually. Most likely, Mosquirix will become another tool, like bed nets, to prevent the spread of the disease: A trial published in September found that the vaccine, together with preventative drugs during the high-transmission seasons, was more effective in preventing hospitalizations than either method alone.

Before widespread distribution can begin, the board for the global vaccine alliance, Gavi, must approve the shots and order doses for countries that sign up, a process that is expected to take around a year. However, it’s unclear to what extent the COVID-19 pandemic will affect the process, with Gavi and national public-health agencies currently focused on procuring doses amid vaccine hoarding by wealthy nations.