On Wednesday night, 24 hours later than expected, news organizations announced that Phil Murphy had been reelected governor of New Jersey. The narrow victory was a dumbfounding rebuke of the state’s Democrats, who went into the election with the drink-clinking serenity of the ensemble in the first act of the Poseidon Adventure. With the exception of one or two outliers, the polls all showed Murphy winning by eight or more points. Instead, his party got smacked by a Republican wave. Murphy managed to win by a whisker, thanks to late-arriving results out of machine-run North Jersey counties. But there were shocking results down the ballot. In South Jersey, the president of the state senate, an ally of the state’s most powerful political boss, lost to a truck driver who reported spending $2,160 on his campaign.

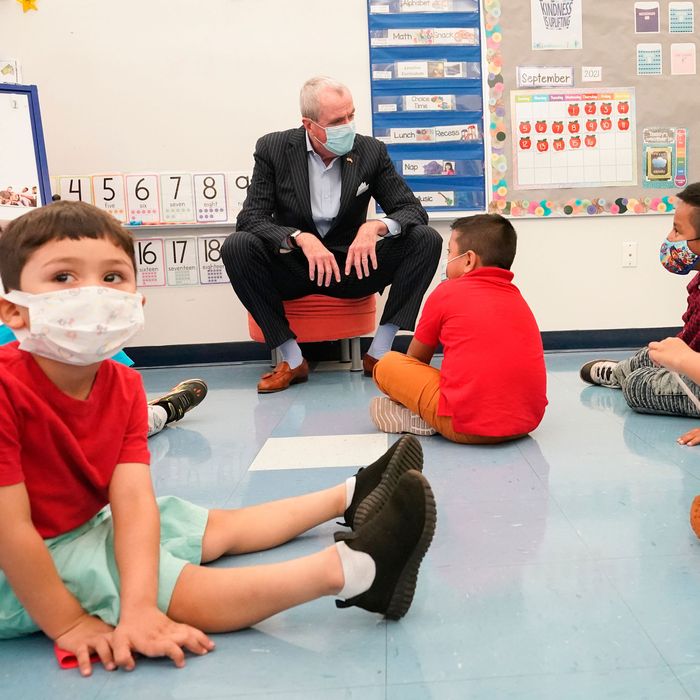

What happened? Political analysts are like weathermen — they’ll do a good job of telling us why it stormed yesterday, once they have a chance to parse the numbers. But in the absence of hard evidence, a consensus is already starting to emerge: It was the schools. Although culture-war controversies over race and curriculum are more muted in New Jersey than in Virginia, the Republican candidate Jack Ciattarelli, a former state legislator, ran as a Regular Jersey Guy who attacked high property taxes, Murphy’s mask and vaccine mandates, and the way schools are teaching about race. To say that the result was a cultural backlash, though, is an oversimplification. Or actually, come to think of it, an overcomplication. For a lot of parents, it was pretty simple. The public schools were closed for much longer than necessary, and Murphy did little to open them.

Who could have predicted this? Well, anyone with a kid in public school during the pandemic paralysis of last year. I won’t pretend that my own experience is more meaningful than anyone else’s. But the singular of data is anecdote, so let me tell you what happened in my town.

In 2015, when my son was 3, I moved to the suburb of Montclair, New Jersey, because, well, of course I would. One year later, an election was held, and Donald Trump won it. Everyone in town was very upset. There were marches and vigils. When an elderly Trump supporter was arrested for tagging a storefront across the street from my local coffee shop with MAGA graffiti, it made national news. A group called “NJ-11 for Change” spontaneously coalesced on Facebook and started to protest against the local Republican congressman, a moderate committee chairman whose family had held the seat on and off since the Revolutionary War. The group received adoring press coverage and went on Rachel Maddow’s show. The Republican decided to retire. An impressively credentialed former prosecutor and public school mom named Mikie Sherrill emerged to run for the seat. When Politico later profiled her, calling her “the most important new woman in Congress,” they took her picture at the diner around the corner from the coffee shop, a place I often took my son for pancakes after soccer on Saturdays. It’s that kind of town.

A year after Trump’s election, my son went to kindergarten at the elementary school across the street from our house. We held his hand when we crossed at the corner, and didn’t think much about what happened once he walked in the door. The tax bill for our three-bedroom home was $19,000 a year.

Then, one day in 2020, school was dismissed, and the building across the street didn’t reopen to students for another 13 months. As a parent, this pandemic paralysis was emotionally excruciating. (I ended up writing about it, though for the purpose of maintaining some distance, and also my sanity, I focused my reporting mainly on Maplewood, a nearby town.) Suddenly, it felt like everyone in Montclair was fighting over everything, but most of all about the schools. Some parents were protesting, organizing a pro-reopening group called Montclair FAIL. (The group later changed its leadership and it now goes by a less-polarizing acronym Montclair PAGE.) Some parents were deathly afraid to send their kids back. Some parents were starting to wonder why a district with an annual budget of roughly $130 million was unable to maintain basic systems like ventilation. And everyone was wondering where our Democratic governor was on all of this.

But Murphy was nowhere to be seen. The former Goldman Sachs man had won high marks from the public for his handling of the public-health emergency, implementing McKinsey-tested interventions and offering genial Irish eulogies for the dead, signing off with “God bless ‘em.” But when it came to education, he dodged the argument, delegating all the reopening decisions to beleaguered superintendents and school boards, citing the principle of local control.

There was a brief moment, in the summer of 2020, when it appeared as if Murphy might be edging toward a more proactive role. The scientific evidence was already pretty clear by this time: With masking and contact tracing, it would be possible to resume in-person learning. Other states were already doing so. But many teachers were understandably terrified. Over a few days in August, the state’s largest and most powerful teachers union, the New Jersey Education Association, declared that it was unsafe to return to classrooms, and Murphy immediately reversed himself, saying local districts could continue with remote learning if they provided a “good reason.” Oftentimes, that reason turned out to be the objection of the unionized workforce. It was hard to escape the suspicion that Murphy was removing himself because he was unwilling to cross NJEA, his most important political ally. Among other things, the union had secretly funneled millions into a super-PAC formed to advocate for Murphy’s policy objectives.

And who was in charge of the union? That’s where things got particularly interesting in Montclair. The most powerful official in NJEA, an ambitious up-and-comer named Sean Spiller, was also our town’s mayor. In the midst of the pandemic lockdown, Spiller had narrowly won a low-turnout election marred by the flawed implementation of the new vote-by-mail system. Murphy took time out from his crisis-management duties and came to swear in the union boss. In another town, this might not have presented a blatant conflict of interest. Most municipalities in New Jersey have elected school boards that control the budget and handle contract negotiations with teachers. But Montclair had an archaic form of government in which the mayor had the sole discretion to appoint all of the members of the school board. It was responsible for hiring — and, with depressing regularity, forcing out or firing — the district’s superintendent.

The present superintendent, a brand-new guy, had been handed the job of reopening the schools over the mayor’s organization’s objections. The teachers union refused to come back to the classroom, even after vaccines were widely available, and the two sides ended up in court. In the wake of the lawsuit, the mayor placed three new appointees on the board, kicking off one of the only parents of school-age children on it. The displaced board member attacked Spiller in turn, saying he had been removed “because I dared to represent the interests of our children, rather than a political machine.” Spiller has consistently refused to acknowledge the existence of any conflict of interest. He did not respond to a request for comment, but yesterday, in his capacity as the statewide union president, he put out a triumphant statement that trumpeted the NJEA’s status as one of “the first organizations to endorse” Murphy. The union’s new secretary-treasurer Petal Robertson, who, prior to her election to that extremely well-compensated position earlier this year, was the NJEA local head in Montclair and the vociferous leader of the opposition to reopening the schools for in-person learning, called Murphy’s victory “a win for New Jersey’s families.”

The height of the reopening conflict coincided with the 2020 presidential campaign and the ensuing postelection chaos. This created a bizarre bifurcation within communities like ours. The election results showed that people who lived in Montclair — with the exception of a few MAGA cranks — were overwhelmingly opposed to Trump. Meanwhile, everyone you talked to was furious with the local Democrats who were mismanaging the schools. The cognitive dissonance worked the other way, too. The Biden victory marked the culmination of the Trump-era realignment of the suburbs, driven primarily — both in terms of numbers and volunteer energy — by college-educated professional women. Yet the policy decisions made by local Democrats, particularly around schools, worked against the interests of these very valuable voters.

Many parents — women especially — found themselves acting as involuntary substitute teachers and full-time caregivers, continually on call to dig out crayons, serve snacks, and solve technical problems with the Zoom. It was only natural that many of these frustrated parents started to pay closer attention to what was happening in the classroom — it was right there in their home. In the run-up to the election in Virginia, which was considered the one to watch, the media mainly focused — probably too much, in retrospect — on Fox News–driven controversies over critical race theory that erupted in conservative suburbs in Virginia. These were only one culturally specific manifestation of a universal ramification of remote learning. Parents were watching. They were Zooming into school board meetings. They were bombarding principals with emails. They were livid; they wanted to know who was in charge.

But where was the manager? Last June, at the end of the school year, Murphy made a regulatory change that effectively prevented districts from using remote learning this fall, and all the kids went back to school, wearing masks, just as they maybe could have done 12 months earlier. Murphy’s aides concede that the delay was politically damaging, although they also say it could have been worse if the governor had not acted decisively when he did. “The bottom line is, you have to make tough decisions when you’re a governor, particularly during a pandemic,” says Mahen Gunaratna, Murphy’s communication director. “But sometimes there can be a backlash to making those tough calls.” Murphy’s campaign attributes the uncomfortably narrow margin to a confluence of two factors: Democrats saw the usual odd-year falloff in electoral participation on the Democratic side, while casual Trump voters turned out at a level closer to that of last year’s presidential race. One Murphy adviser said yesterday that he saw little evidence of a connection between that political dynamic and school closures. “What happened was we saw unbelievably historic turnout on the other side,” he said. “In a lot of the areas with red turnout, their schools were open.” Maybe the suburban Democrats will return in 2022, when Sherrill and a number of other members of Congress elected in the 2018 blue wave face potentially tough battles, albeit in new districts designed by a friendly administration.

Then again, maybe the effect will end up lasting longer than one cycle. On a localized level, the damage — to the kids, to the emotional health of parents and teachers, to the public school system, and to Democrats — cuts deep. The longtime principal of my son’s school announced her retirement and addressed a school board meeting, where she tried to talk about deeper issues in the schools that the pandemic had revealed. The chair of the school board muted her. The principal who replaced her is an energetic young educator, but the school’s student body appears to have decreased substantially. Over the summer, the Montclair Local newspaper reported that district-wide kindergarten enrollment was down 40 percent from where it was before the pandemic. Official figures have not yet been released, but informal estimates circulating among parents suggest a staggering drop on the elementary level, something in the vicinity of 20 percent.

Parents who managed to get their kids through the endless wait list for the fancy private school in town, which held classes all last year, talk about the decision in furtive, mildly abashed tones, like they cut the line at the Kabul airport. Two of the Maplewood parents I wrote about in my story earlier this year decided to move to other towns, at least partly out of dismay with how the district handled reopening. One of our neighbors, whose son played baseball with my kid, ended up moving to North Carolina, citing the same reason. My wife and I have decided to stick it out in public school — we love the place and the people inside it — but this fall, for the first time in our lives, we stuck a campaign sign in our front yard. It was for a referendum that parents in Montclair managed to get on the ballot, calling for the abolition of the politically appointed school board, and its replacement with one elected by the community. “ELECTED BOE: YES,” it says, in Crayola-colored letters. The local Democratic machine tried to use demagoguery to defeat the referendum, claiming that elections would inevitably lead to the abolition of one of the best things about Montclair’s schools, its magnet system, which is meant to ensure racial balance.

The referendum passed with 70 percent of the vote. Even with that passionately contested issue on the ballot, though, turnout was around half of what it was for the 2020 presidential election, and roughly at the same level as 2017, when Murphy faced little serious opposition. My wife, a socially liberal professional woman, voted for the school board but left her ballot blank in the race for governor. She had sworn to me that she would never cast a vote for Phil Murphy again after our son spent the majority of last school year learning in our dining room. Many of the public school parents I know around here made similar decisions. “I feel like he harmed my daughter,” one of them texted me yesterday. “I just couldn’t do it.”

An extreme reaction? Maybe. But people tend to get mad — incandescently furious — when they think you’re hurting their kids. The provision of public education is among the most basic functions of government. And for many, many, many months, New Jersey’s government fucked it up. What’s more, the Democrats who run that government assured the public that they saw the problem yet acted like they had higher priorities. For the most part, they seem to have been complacent in the belief that the free-floating anger would remain confined to Facebook groups and school board Zooms.

But it finally found its object on Tuesday.

This story has been updated to more accurately reflect the amount Ed Durr spent to unseat the state senate president.