A couple months before Tammy Rodriguez’s daughter Selena died in 2021, the two were in the car, driving home. Selena, 10 years old at the time, was sitting in the front seat, scrolling on her phone, when her battery died and the device was reduced to its bare shape: a slab of rounded glass. Selena tapped on the black screen, seeing only her own face reflected back. She asked to use her mother’s phone, but Rodriguez refused. They’d be home in a few minutes, she told her. Wait.

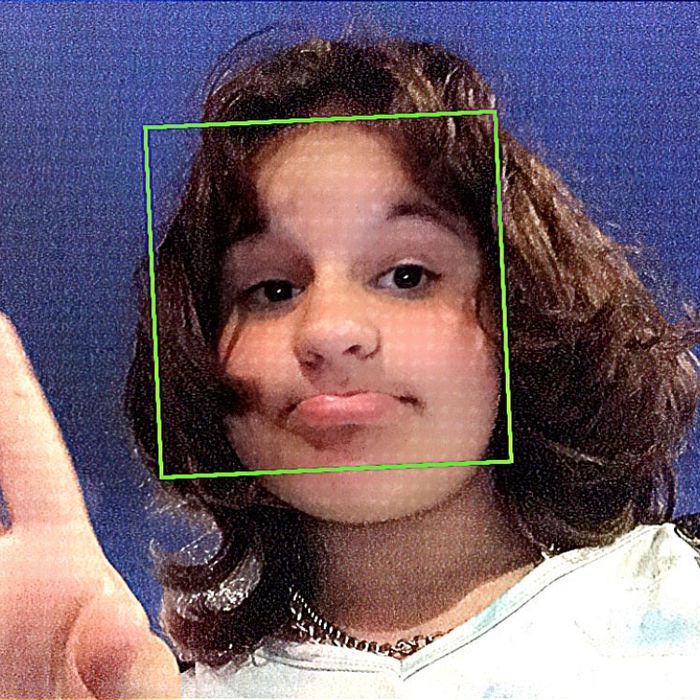

But Selena was persistent. She was big for her age, tall and broad-shouldered, with defiant brown eyes and wispy curls. She pleaded with her mother, gripping her arm and refusing to let go. Rodriguez struggled to keep hold of the steering wheel. Her arm, she told me, was bruised for a week.

Months earlier, Selena had broken her sister Destiny’s nose after Destiny had taken her phone and refused to give it back. (Her sister is 12 years older than her.) By both her mother and sister’s account, Selena, who was diagnosed at 5 years old with ADHD, had developed a kind of obsession with social media — her likes and followers, her cyberfriends and cyberbullies, and the cyberstrangers with whom she regularly connected, many of them grown men who lived hundreds, sometimes thousands of miles away. She was on the apps most of the day and well into the night, and her mood would swing violently on account of something that someone said online or the loss of a follower.

One therapist who evaluated Selena in the family’s hometown of Enfield, Connecticut, told her mother it was the “worst case of social-media addiction” she’d ever seen, and it was this addiction, her family later claimed, that would lead Selena to post a video to her Snapchat Story in July 2021, at 11 years old, in which she can be seen taking two of her mother’s Wellbutrin pills and a glug of soda, sticking out her tongue, and holding up a peace sign. The NF song “Paralyzed” played softly in the background: “I’m paralyzed. Where are my feelings? / I no longer feel things.” Offscreen, Selena overdosed on the medication. She was found by her mother that same day.

After Selena’s death, Rodriguez contacted an organization called the Social Media Victims Law Center. Her case would become the first in a multi-district litigation involving lawsuits from over 100 parents and teenagers (and one from the Seattle public-school district) against social-media giants including Facebook, Snapchat, Instagram, and TikTok. These companies, plaintiffs claimed, were responsible for a litany of mental-health crises among kids and teenagers — perhaps even responsible for the larger trend of declining mental health across the country — and they needed to be “held accountable,” said Matthew Bergman, founder of the law center and one of the architects of the suit.

Until recently, lawsuits such as this one would have had little to no shot at making it to trial, instead stymied by a modest 26 words in the legal code. Section 230 of the Digital Services Act of 1996 is often called the Magna Carta of the internet, the law that has dictated our era of web imperialism. A “safe harbor,” the statute protects online platforms from liability for any user-generated information on their sites along with allowing them the freedom to establish their own content-moderation practices, and it has traditionally been broadly interpreted in the courts. But now, a new league of social-media reformists, many of them parents, say it’s time for that to change. And for the first time, lawmakers are listening.

Whether they have lost children to suicide, a TikTok challenge, or an eating disorder, these parents and activists allege that Section 230 has allowed platforms to encourage addiction, extremism, and hatred for the sake of engagement — and with total impunity. Along with a number of new regulatory proposals, efforts to narrow the scope of Section 230 have mushroomed in the past year. In February, for the first time, Section 230 was challenged in oral arguments at the Supreme Court in two cases that accuse YouTube and Twitter of helping to spread terrorist messages.

But it is the impact that social media is having on children and teenagers — who, according to studies, are undergoing historic levels of anxiety, depression, and body-image issues — that has drawn the most attention and fomented enough outrage to spark action from lawmakers. It’s a natural, if hugely contested, step in logic: If social media is making people miserable, if it’s leading kids to have suicidal thoughts, then companies must be incentivized to prevent and mitigate risks to mental health. The risk is that they may upend the internet as we know it in the process.

Rodriguez stopped sleeping in the months that followed Selena’s death and spent many nights as her daughter once had, scrolling. One of those nights, on Facebook, she saw a well-placed ad for Bergman’s law center. Something about the law firm’s bold logo, featuring a digital illustration of a smartphone, its screen filled by a courthouse, caught her attention. “Is my child addicted to social media?” its website asks. Rodriguez filled out a form that same night. She received a call “pretty much immediately.”

Bergman has practiced law for 30 years, 25 of which have been in injury law. He founded the law center in the fall of 2021 after realizing there were “acute injuries happening right before our very eyes involving vulnerable kids.” Before that, he primarily worked on asbestos cases. In Bergman’s view, getting these cases to discovery is paramount in reforming the industry. He told me that the law center — the only law center in the country dedicated to social-media injury cases — currently represents over 1,500 parents and that about 100 of those cases have been filed. “I’m surprised by the volume,” he said. “I’m surprised by the uniformity.” It was only after the law center investigated Selena’s case that Rodriguez learned the extent of Selena’s app use. “They found that she had seven Instagram accounts,” she told me. “I had no idea about that.”

Kristin Bride, a prominent social-media-reform advocate, lost her 16-year-old son, Carson, to suicide in 2020 after he experienced relentless bullying on two of Snapchat’s anonymous messaging apps, YOLO and LMK. Bride said she wasn’t initially interested in pursuing legal action, but when she reached out to YOLO four times and never heard back, she “really didn’t know where to turn.” After watching The Social Dilemma, Jeff Orlowski-Yang’s 2020 documentary about the dangers of social media, she approached the Center for Humane Technology’s Tristan Harris, one of the documentary’s interviewees. He connected her with Fairplay, a nonprofit that works to end targeted ads to children. Through the company, she met Joann Bogard, who had lost her son to TikTok’s “Blackout Challenge,” a trend in which kids, sometimes as young as 9 years old, filmed themselves holding their breath until they passed out. Together, they founded the Online Harms Prevention work group, which has since grown to over 40 members, all parents.

The group has worked closely with Senator Richard Blumenthal in drafting the Kids Online Safety Act (KOSA), which would require social-networking sites to prevent minors from seeing content related to self-harm, suicide, drugs, and eating disorders. Bride also has a separate class-action lawsuit against Snapchat, YOLO, and LMK. (Snapchat has since terminated YOLO and LMK’s services through its app.) Her California suit against YOLO and LMK seeking product liability for faulty design was dismissed in January on the basis of Section 230.

Bride said her ideal world sees the development of “some sort of regulatory commission that looks at these products before they get mass-marketed.” But she would also like to eventually see Section 230 reform. By her measure, Carson’s death had little to do with what was actually said to him — i.e. the “content” he engaged with. It was the apps’ design — allowing and encouraging anonymity — that mainlined cruelty into her son’s system, and that design should not be protected by Section 230. After Carson died, Bride learned that the last thing he’d searched on his phone was a hack to find out whom his anonymous bullies were: “To see all the messaging, and knowing how sensitive he was, and the message to a girl he trusted asking, ‘Hey, do you know who’s doing this to me?’ That’s when it clicked.”

A big problem for social-media reformists is that it’s impossible to say with any certainty whether social media really is the source of so much widespread angst, even when it seems obvious to anyone who has been on the apps that they can be very bad for you. In her book iGen, psychologist Jean M. Twenge declared, “The sudden, sharp rise in depressive symptoms occurred at almost exactly the same time that smartphones became ubiquitous and in-person interaction plummeted. That seems like too much of a coincidence for the trends not to be connected, especially because spending more time on social media and less time on in-person social interaction is correlated with depression.”

But at best, the data on teenagers is mixed — at worst, wildly mixed. The challenges of conducting longitudinal studies on kids and teenagers, along with the difficulty of isolating social media from other external factors (such as a global pandemic), have made it exceedingly hard to establish a clear causal relationship between mental health and social-media use.

“There’s a lot of heterogeneity in the effects associated with social media,” said Jeff Hancock, founding director of the Stanford Social Media Lab. “There’s a bunch of people for whom it doesn’t really seem to matter for their well-being. There’s a bunch of people who are negatively affected. And there’s a bunch of people who are positively affected.” Plus, “Any time you’re talking about a large-scale phenomenon,” said Jacqueline Nesi, a psychologist whose research focuses on these issues, “it’s really difficult to identify one specific cause.” Some of Nesi’s research indicated that kids who had experienced cyberbullying had also benefited the most from online communities.

One of the peculiarities of social-media product-liability cases is that they require a kind of forensic gridding of mental health. Could Selena’s pain have been tempered off the apps? Was she harboring such a deep well of loneliness and insecurity that she would have found other — potentially just as destructive — means of accessing it? Or did the apps make her pain especially vulnerable to exploitation? Rodriguez recalled Selena talking about her follower count “constantly,” going to extreme lengths to learn the identity of anyone who unfollowed her. She would take her mother’s phone at night, even adding her own fingerprint on the device without her knowledge, said Rodriguez, just to have another device to use. In addition to negative comments and messages from classmates, she’d also been contacted by men soliciting nude photos of her, which she sometimes seemed puzzled, even indignant, about. “I’m Lewis will you be my sugar baby I will be giving you $300 twice in a week. Let me know if you are interested,” one man wrote. “No cause I am 12,” she said. “Okay,” he said. “Your like 30,” she said. “Yes,” he said. “You can get arrested,” she said. Other times, she just sent them the nudes.

I asked Hancock whether teenagers whose anxiety and depression could be linked to social media shared any other traits, anything that potentially made them more sensitive to negative effects of the sites. With the caveat that they simply don’t know enough yet, he said it did seem as though girls, especially young girls experiencing puberty, were more vulnerable.

Part of Hancock’s work includes assessing how to provide people with the tools they need to feel more in control of their experiences on social media. “This is lame, I guess, because I’m a professor, but education is the only long-term answer here,” he told me. “We literally give kids and adults these tools with zero training.” He added that, more than gambling or alcohol, the car industry seems the most analogous to social media in that we recognize the societal value despite it being a potentially dangerous technology. “We don’t ban them; we don’t ban people’s use,” he said. Instead, we require driving lessons and imposed safety regulations. Whereas with social media, “it just feels like, Okay, hop in the car.”

Hany Farid, senior adviser for the Counter Extremism Project and a computer-science professor at UC Berkeley, provided me with a different car analogy involving a landmark case that wrought reform in the auto industry. The first round of Ford Pinto cars on the market, those that came to define the ’70s with their muted earth tones and buggy headlights, were faultily designed: The gas tank was in the wrong place, cars were exploding if they were hit in just the right spot, and people were dying. “And what the car company said is, ‘Okay, we have two options: We can either recall all these cars, fix the gas tanks, and send ’em back out. It’s gonna cost us X million dollars. Or we can just leave them as it is — let the people die, and we’ll settle the lawsuits. And that will cost us less,’” said Farid. “So that’s what they did.”

It’s widely accepted that repealing Section 230 outright — i.e. imposing liability on platforms for any speech they host — would be, well, a total disaster. But many internet lawyers and technologists argue that even limiting the scope of its protections by narrowing its interpretation in the courts (which is what would have to happen for a case like Rodriguez’s to get before a judge) could have devastating repercussions. Without the broad reach of Section 230 protections, said Cathy Gellis, an internet lawyer who primarily represents small start-ups and internet companies, litigation could make it prohibitively expensive to host and operate a website, likely pushing the web further in the direction of a monopoly model. That ambient threat may also incentivize companies to remove any post that has even the slightest chance of being legally questionable, such as abortion resources in abortion-hostile states. “Even one legal challenge over one user’s content can lead to a legal threat, and if you have to go through a process of litigating whether you should be liable for that legal threat, your money is gone,” she told me.

“Every time Section 230 is undermined, it introduces complicated, often vague, and ambiguous legal questions,” said Jess Miers, a lawyer, technologist, and former analyst at Google (her trade group receives funding from major tech companies). “And those questions almost always bring up a question of fact, and questions of fact cannot be resolved at the motion-to-dismiss level” — which means outsize legal costs for defendants.

In the past, efforts to reform Section 230 or impose stipulations have been dangerously myopic, one of the most notable being the Stop Enabling Sex Traffickers Act and the Fight Online Sex Trafficking Act. The bills were written to help prevent human trafficking but ultimately ended up disempowering sex workers by making the platforms where they would normally be able to safely advertise their services and vet potential clients legally liable for such posts.

And beyond the difficulty in drafting the legislation, the polarization of 230 reform has proved especially deadening. It was Donald Trump who first imbued the law with a political charge on the campaign trail in 2016, effectively making it a synonym for censorship. “We have to get rid of Section 230,” Trump said at one Georgia rally, “or you’re not going to have a country very long.” (The crowd members, to their credit, seemed deeply confused.) The first part of Section 230 shields internet companies from legal action for user-generated content on their platforms, while the second part enables them to moderate harmful content and take things down. Not particularly known for reliably non-harmful content, conservatives eventually began to feel targeted by the latter. In 2019, Senator Josh Hawley introduced legislation that would require tech companies to prove “by clear and convincing evidence that their algorithms and content-removal practices are politically neutral,” and in 2020, Trump signed a similarly themed executive order that would limit Section 230’s scope of protection on the basis of “selective censorship.”

Last year, both Texas and Florida passed laws that would hold platforms liable for suspending users and removing posts, an effort that lawmakers saw as a corrective to unfair bias against conservative viewpoints. “If big-tech censors enforce rules inconsistently, to discriminate in favor of the dominant Silicon Valley ideology, they will now be held accountable,” said Florida governor Ron DeSantis. The Florida law was struck down by an appeals court, while an appeal to the Texas law is set to be heard by the Supreme Court later this year.

Democrats have conversely begun targeting Section 230 on the grounds that it doesn’t moderate enough. In July 2021, President Biden called for a repeal of Section 230 based on the proliferation of COVID-19 misinformation on Facebook, which he said was “killing people.” Senator Amy Klobuchar proposed the Health Misinformation Act a couple weeks later, which aimed to hold platforms liable for when their algorithms promote health misinformation related to an “existing public-health emergency.”

But if lawmakers are divided on the way big tech moderates its political content, they are increasingly coming to a bipartisan consensus that the internet is bad for kids. In addition to KOSA, a number of other child-centric internet bills have been proposed at both the federal and state level. In September, California, where Rodriguez’s suit is being litigated, passed the California Age-Appropriate Design Code Act, which requires social-media companies to enact a wide-ranging set of safeguards for users under 18, including ensuring data privacy and determining the age of child users with a “reasonable” level of certainty. This past September, senators Lindsey Graham and Elizabeth Warren announced they were teaming up to establish a digital regulatory commission “that would have power to shut these sites down if they’re not doing best business practices to protect children from sexual exploitation online.”

Earlier this year, Bride testified in a Senate Judiciary Committee hearing called “Protecting Our Children Online.” On the day she testified, a silver heart-shaped locket hung from her neck, and a button emblazoned with a photo of her son was pinned to her blazer. He smiles in the picture, his hair tousled. The same photo, larger, was displayed next to her on the table with the words “Carson Bride, 2003–2020, Forever 16.”

“I speak before you today with tremendous responsibility to represent the many other parents who’ve lost their kids to social-media harms. Our numbers continue to grow exponentially with teen deaths, from dangerous online challenges to sextortion, fentanyl-laced drugs, and eating disorders,” Bride said, her voice booming. “Let us be clear: These are not coincidences, accidents, or unforeseen consequences. These are the direct result of products designed to hook and monetize America’s children.”

Reformists are largely targeting what has become the most commonly referenced source of internet villainy: the algorithm. The algorithm, a catchall term for the curatorial sorting of anything from a news feed to Google search results, is both everywhere and nowhere. It is at the core of most internet grievances, and yet most people — including those who are meant to be legislating those grievances — don’t understand it. It’s like if math were God (with a slightly wider reach). The plaintiffs in the Supreme Court case Gonzalez v. Google alleged that YouTube (along with its parent company, Google) had knowingly pushed and amplified ISIS-related content through its recommendation algorithms. The other case before the Court, Twitter, Inc. v. Taamneh, took these accusations a step further: The prosecution argued that platforms were aiding and abetting terrorists by allowing them on their sites as well as through algorithms that circulated terrorists’ posts.

The algorithm conversation is one that makes technologists wary. For laymen, the word conjures fragmented sequences of numbers and letters that could just as easily choose your next song on Spotify as send your red-pilled neighbor down a rabbit hole that ends in tragedy. Still, the fact remains that algorithms are the core functionality of the internet. In other words, reducing the “harmful” content that kids come in contact with isn’t as simple as changing a line of code in an algorithm, and to strip the internet of them would potentially mean “you would probably see more ISIS content because it wouldn’t be tailored to your recommendations or interests anymore,” said Miers. “I don’t think there’s a practical technological solution there because, again, any way the service displays information, it will be done so algorithmically.”

But even Miers conceded there is a conflict of interest in how strongly social-media companies value engagement, since what often drives engagement may otherwise be considered “harmful” content. (Although she stressed that that conflict isn’t enough to interfere with their ability to self-regulate.) And still the larger problem, reformists say, is that we don’t know how these algorithms work. Because cases against social-media companies never make it to court — where they would likely be required to disclose specific company practices — there’s no real way of knowing whether there actually is algorithmic bias.

In a Senate Judiciary Committee meeting following the Gonzalez and Taamneh cases, Mary Anne Franks, a law professor at the University of Miami and president of the Cyber Civil Rights Initiative, said that evidence that would potentially be revealed through these trials is paramount in understanding how to move forward. “Litigation is one of the most powerful ways to change an industry, and it’s not just because of the ultimate outcome in those cases but also because of the discovery in those cases,” she said. “What we get to see, instead of having to wait for whistleblowers or wait for journalists, is actually the documents themselves — internal documents about what you knew, when you knew it, and what you were doing.”

In some ways, the trajectory of internet reform in the U.S. is a slower version of that which has been seen in the U.K. and Europe. The Age Appropriate Design Code was enacted in Britain in September 2021, imposing 15 new standards on internet companies, many of which mirror those of KOSA and similar bills. YouTube, for example, had to turn off auto-play for kids, while Google stopped targeted advertising to them, among other things. The new regulation also defined kids as anyone under 18 — a huge point of contention for tech companies. If passed, the U.K.’s pending Online Safety Bill would require companies to publish risk assessments of their platforms and provide parents with a clear avenue for reporting content. Tech companies have argued that the legislation compromises users’ data by forcing companies to monitor them more closely, a kind of “state surveillance and censorship” that is “far closer to the approach seen from regimes in Russia and China than anything in Europe or the U.S.,” as Matthew Hodgson, co-founder of the encrypted-messaging service Element, put it.

But in just the past five years or so, our view of technology has undergone radical revision. The idea that the state is a greater threat to privacy than the apps is now in question. Bride told me that kids and teens only recently began engaging with Fairplay’s messaging about limiting screen time and protecting yourself online. “They would go into schools and talk about the harms of social media like a decade ago, and they’d be booed off the stage,” she said. “But now everyone gets it. There is not anyone that I speak to that’s like, ‘I don’t understand.’”

In November, Europe passed the Digital Services Act, which is probably the closest any government has come to imposing strict regulations on the internet writ large. Among other things, the DSA would impose farther-reaching content-moderation protocols onto platforms and require them to refrain from “dark pattern” nudges to shape behavior and choices. Although many parts of Europe had already put knowledge-based liability on the platforms, the DSA would also standardize and extend those obligations when it goes into effect for very large online platforms in mid-to-late April.

Much of the DSA wouldn’t work in the U.S., primarily because of the First Amendment. For one thing, the law requires annual audits and written reports to assess how well platforms are addressing and mitigating terrorism risks or anything that could cause “a real and foreseeable negative impact on public health, public security, civil discourse, political participation and equality,” which, through selective interpretation, could result in the repression of speech. In other words, said Daphne Keller, a law professor at Stanford, “it would be pretty easy for the regulator to be like, ‘Yeah, you didn’t mitigate the terrorism risk enough.’”

Keller said requiring companies to ask users to make customized feed settings in exchange for their data may be one technological solution. As for the argument that curation algorithms are fundamental design decisions that shouldn’t be protected by Section 230, she said that felt “a little bit like sleight of hand” because the conversation was still, at its core, about content. Imposing fuzzy, undefined liability on platforms’ design as a basis for the kind of content they allow to circulate, she said, may only produce more confusion and litigation with little actual payoff. Gellis, the internet lawyer, told me efforts should instead be put in “specific regulation targeting the things that are actually bothering us, as opposed to putting all the weight on Section 230 and thinking we can somehow retune it in a way to deal only with those problems without undermining it in general.”

In his book Speech Police: The Global Struggle to Govern the Internet, David Kaye said that, in the past, giving social-media companies space to regulate themselves made sense given their size. Now, though, their “decisions don’t just have branding implications in the marketplace. They influence public space, public conversation, democratic choice, access to information, and perception of the freedom of expression.” He also noted that “one simple question must be answered in order to get internet regulation correct: Who is in charge?”

Part of the problem, said Farid, is that no one really wants to be. “Everybody wants it and nobody wants it,” he told me. “There’s just no real ownership of this sector.” But certainly large-scale regulation is beginning to seem inevitable. Every day, news breaks of smarter, better artificial intelligence that’s helping us to cheat on tests or cure cancer or commit fraud or write books or find love. There are questions of racial bias and surveillance and what makes humans human. “We’re trying to fix yesterday’s problem,” said Farid, “and today’s problems are here.”

Last month, Rodriguez traveled to Washington with Bergman’s team and around a dozen other parents and teens involved in their lawsuit to hear the Gonzalez and Taamneh arguments at the Supreme Court. It was a comfort, said Rodriguez, to meet people who had gone through the same thing, who had lost kids to some unknowable, all-consuming force. “Just having that bond with these other mothers who know how it feels,” she said, was encouraging. “People can say they know, of course — or, you know, that they can only imagine or whatever — but these people really, actually know.” They’re also now all friends, she added, on Facebook.