This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

The Hotel Captain Cook in downtown Anchorage, Alaska, commemorates the 18th-century explorer who circumnavigated the globe twice, “discovering” vast swaths of it for British imperialists before being stabbed to death while attempting to kidnap a Hawaiian chief. It is a somewhat inauspicious place to consider the state of the western-led, rules-based international order, but it’s also roughly equidistant from Beijing and Washington, D.C. And just before the first day of spring, as the temperature outside dipped below zero, the Captain Cook’s ballroom became the center of the geopolitical realm.

Inside, the U.S. and China were conducting their first major encounter of the Biden era. America’s new secretary of State, Antony Blinken, started the meeting innocuously enough, but included some swipes at China’s pattern of cyberattacks, human-rights abuses in Xinjiang, and undermining of democracy in Hong Kong and Taiwan. Beijing’s top diplomats, Yang Jiechi and Wang Yi, were given two minutes each to respond. Instead, they exploded protocol with a 20-minute diatribe about their hosts’ lack of standing to lecture anyone on anything. “We do not believe in invading through the use of force, or to topple other regimes through various means, or to massacre the people of other countries,” Yang said through a translator, before observing that “many people within the United States actually have little confidence in the democracy of the United States” and invoking Black Lives Matter.

Blinken, who is 58, stared at Yang from across the room and began taking notes. Under a tamed sweep of wavy, graying hair, he wore a black face mask that obscured any trace of a reaction — not that the lifelong globe-trotter would have betrayed one anyway. Yang continued, “I don’t think the overwhelming majority of countries in the world would recognize that the ‘universal values’ advocated by the United States, or that the opinion of the United States, could represent international public opinion. And those countries would not recognize that the rules made by a small number of people would serve as the basis for the international order.”

Blinken knew his opening remarks would elicit some kind of reaction, but Yang’s nearly bellicose response — “Between our two countries, we’ve had confrontation in the past, and the result did not serve the United States well” — was more provocation than the American side had expected. As aides ushered a small gaggle of journalists out the door as scheduled, Blinken decided he didn’t want the Chinese to have the last word. “Hold on one second, please! Hold on,” he said, reaching out an arm, and began a monologue of his own.

“A hallmark of our leadership, of our engagement in the world, is our alliances and our partnerships that have been built on a totally voluntary basis,” Blinken said. “And it is something that President Biden is committed to reinvigorating. And there’s one more hallmark of our leadership here at home, and that’s a constant quest to, as we say, form a more perfect union. And that quest, by definition, acknowledges our imperfections, acknowledges that we’re not perfect. We make mistakes, we have reversals, we take steps back. But what we’ve done throughout our history is to confront those challenges openly, publicly, transparently, not trying to ignore them, not trying to pretend they don’t exist, not trying to sweep them under a rug. And sometimes it’s painful, sometimes it’s ugly, but each and every time, we have come out stronger, better, more united as a country.”

The civics lecture — which came amid a wave of American and allied sanctions on Chinese officials — was a high-minded throwback, unlike anything to come out of an American diplomat’s mouth in four years. And the Chinese, who spent those years in daily, often disorienting combat with Blinken’s predecessors, weren’t buying it. “My bad. When I entered this room, I should have reminded the U.S. side of paying attention to its tone in our respective opening remarks, but I didn’t,” Yang shot back, ignoring a half-plea, half-warning from Blinken’s colleague, the national security adviser Jake Sullivan, to keep things constructive. “I think we thought too well of the United States.”

One question hanging in the air was whether Blinken, in his own way, might also think too well of his country. He has been advising Joe Biden on foreign policy for nearly two decades, and if there is a Biden doctrine, it could be summarized as like Barack Obama’s but slightly more idealistic: that America should lead the liberal world order, relying heavily on alliances and the symbolic potency of a functioning democracy at home, matched with a credible, but preferably seldom used, threat of force. If the U.S. steps back, Blinken often says, some other country — probably China — will fill the vacuum. To avoid that, both Blinken and Biden like to cite the aspirational Clinton-era axiom that America must “lead with the power of our example, not the example of our power.” The problem is that the world found the example of Trump’s presidency plenty powerful, from treaty trashing to denying election results to storming the Capitol. Even as allies have expressed nearly delirious relief over Biden’s election, representatives from less sympathetic countries have needled the new administration about America’s credibility as an advocate for democracy — sometimes in the press, and sometimes, via video calls, directly to Blinken’s face.

Persuading the rest of the world to adopt his lofty view of America, despite all its smoldering contradictions, is item No. 1 on the secretary’s agenda, which is overflowing with crises. On top of the planet’s pandemic, economic, and climate emergencies, he has had to deal with a coup in Myanmar, the extension of a U.S.-Russian arms treaty, and a North Korean ballistic-missile test. He has handled the fallout from Biden’s agreeing with an interviewer that Vladimir Putin is a “killer” and Putin’s responding with what seemed to be a veiled threat (“I wish him good health”). He has considered whether and how to reengage with Iran over its nuclear program and pondered the future of U.S. involvement in Afghanistan. Meanwhile, back home, Blinken must rebuild the State Department’s staff, both numerically and emotionally, after four years of Trump’s efforts to hollow out the agency.

Blinken’s predecessors acknowledge that the world he’s inheriting is in exceptionally bad shape — including Hillary Clinton, who knows something about starting at rock bottom, having taken over State in the wake of a global financial meltdown and eight years of Bush-inflicted reputational trauma. “Probably it’s fair to say it’s even worse now,” Clinton told me. (And that was a few hours before the fracas in Alaska.) “The effects of the pandemic on the economy and on America’s ability to serve as a model of the world have been pretty stark, and the damage that the former president did to our standing in the world — literally empowering authoritarians, challenging and deriding our friends and allies — means that the skepticism that I encountered when I started reaching out in 2009 is even deeper and wider for Secretary Blinken now.”

Two months into Biden’s term, with Democrats cautiously giddy over his domestic accomplishments, the outlook is far shakier when it comes to the rest of the globe, where many of the policy questions may be intractable — if for no other reason than that no matter how well Blinken performs, there’s little he can do to convince the world that the country won’t one day relapse into another “America First”–style administration.

“Many Europeans are discreetly saying, ‘Well, four years from now, President Trump could be back in the office,’ ” said David O’Sullivan, an Irish diplomat who served as the E.U. ambassador to the U.S. between 2014 and 2019. “It’s the volatility of domestic politics. While it was a relatively handsome victory for President Biden, the fact is that the Republicans didn’t do too badly, and they haven’t gone away. Maybe people don’t want to talk too much about it because the new administration has barely got their feet under the new desk, but in the back of people’s minds, there is this worry. So how deeply do you rebuild the alliance, understanding that in four years it could all be torn up? The contrary view, of course — my view — is this is an opportunity to be seized because you may never see again such a Europe-knowledgeable and Europe-sensitive team in a U.S. administration.”

That’s the sunnier take on foreign policy under Biden. His choice of the impeccably credentialed Blinken, who is not just familiar to but genuinely well liked in both foreign capitals and Washington’s foreign-policy firmament, may be the world’s best shot at reestablishing a stable, American-led liberal consensus. Japanese and Korean officials were delighted to host Blinken’s symbolically important first trip abroad (he had flown to Anchorage from Seoul); his second was to Brussels, where NATO secretary-general Jens Stoltenberg called him “dear Tony” and gushed, “It’s really great to be here together with you for many reasons, but your knowledge, your experience, your background, and your personal commitment to NATO makes you really a secretary which is very much welcomed here at NATO.” Even some top GOP figures seem content with Blinken and his team — and on the most sensitive of issues, no less: “After talking with them about China, I think our views are very congruent,” Jim Risch of Idaho, the highest-ranking Republican on the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, told me recently.

It’s a different story with America’s adversaries, several of whom are eager to test the new administration. “Sophisticated diplomats on the other side know exactly how to rub it in and take advantage of the terrible events that we have seen,” Clinton said. “It’s very difficult to be advocating for democracy when the whole world has seen our democracy literally under attack.”

Malcolm Turnbull, the former prime minister of Australia, told me, “Donald Trump is gone, but there’s a lot of leaders left who want to ‘Make (Insert Country) Great Again.’ Xi Jinping’s one. Modi is another. Putin is obviously another. Erdogan is another. It’s quite a long list.” No matter how popular Blinken and Biden are personally, no diplomat on earth looks at America the same way after Trump. “Everyone breathed a sigh of relief that they’re dealing with safer and more consistent, more predictable, more traditional people,” Turnbull said of the international response to Biden’s election. “But Trump and the forces that he channeled have not gone away. What you’ve got is essentially an assault of populist authoritarianism. I’m always reluctant to call it fascism, but, you know, it looks and feels a lot like that. When the assault on the Capitol is happening, and there were people saying, ‘This is not America, this is not us, this is not who we are’ — well, is that right? That mob, and that huge percentage of Americans who were persuaded by Trump and his amplifiers in the right-wing media that Biden had stolen the election, they looked in every other respect like thoroughly normal Americans with regular jobs, including professionals: doctors, lawyers, police officers, teachers.”

The first time Blinken and I talked, over Zoom, he conceded that the past few months had generated questions about America’s standing. But he framed this, optimistically, as all the more reason to believe in his boss’s long insistence that foreign and domestic policy must work hand in hand. “We very much acknowledge — and I’ve been very forthright and direct about this in conversations with a number of my counterparts — that we’ve gone through, and we are going through, a period where our own democracy is being challenged,” said Blinken in masterfully cautious diplospeak. “In a funny way, I think the experience and our response has also reinforced our ability to be a leader for democracy and human rights around the world.” He gesticulated lightly, as if sprinkling salt on a fillet or conducting a tiny orchestra.

Antony (not Anthony) Blinken’s early years were almost impossibly urbane. Born in 1962, he lived his early years on the Upper East Side, where his father, Donald, a Warburg Pincus founder, was friends with Mark Rothko. Antony attended Dalton (then run by Donald Barr, the father of future attorney general William Barr). His parents divorced, and in 1971 he moved to Paris with his mother, arts patron Judith, and her new husband, Samuel Pisar, whom Blinken has often credited as a formative influence. A Polish Holocaust survivor, Pisar was sent to a labor camp at 13, saw Auschwitz and Dachau, and escaped by fleeing a death march and encountering an American tank. Eventually, he obtained two doctorates and became an adviser to John F. Kennedy and a series of world leaders.

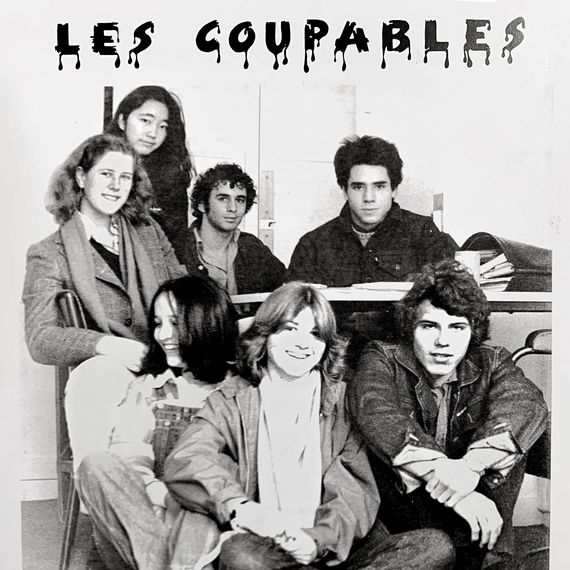

In Paris, Blinken studied at the elite École Jeannine Manuel. The ’70s, defined by the Cold War and Vietnam, were a delicate time to be a young American in western Europe, and people who were then close to Blinken see a direct line from that era to his current perspective. “The combination of his stepfather’s history and his own experience growing up as an American in Paris helps lead to somebody who is deeply committed to America’s role as a world leader, who believes the United States needs to take action against mass atrocities and denounce human-rights abuses, but also to somebody who understands the world doesn’t always see America the way America wants to be seen or sees itself,” said Rob Malley, one of Blinken’s Paris classmates and now the Biden administration’s special envoy to Iran. Malley remembers the teenage Blinken as adept at straddling cultures: The pair treated the opening of the first McDonald’s near them as a major event, held an American-style debate in English class over Israeli-Palestinian relations, and co-founded the school’s first yearbook. Blinken played Pink Floyd’s “Another Brick in the Wall” on his guitar at graduation before returning to the U.S. for Harvard. In the Crimson, he wrote a mix of rock criticism and columns arguing for straightforward liberal American engagement in the world — resisting many of his colleagues’ more aggressive leftward sprint.

Blinken followed a trampled path from Cambridge to The New Republic (where he spent more time performing intern duties than writing), then to Columbia Law School, where he published a book version of his undergraduate thesis; it examined a 1982 dispute between America and Europe over a Soviet pipeline. In Ally Versus Ally, he argued for maintaining transatlantic relations rather than exerting diplomatic pressure on the USSR, articulating a view he still holds today — that “our real source of influence in the world is, whenever possible, working with allies,” in the words of Anthony Gardner, a former American ambassador to the E.U. and a childhood friend from the Upper East Side who has overlapped with Blinken at Harvard, Columbia, and the White House. Blinken got a closer view of American foreign policy when he joined Bill Clinton’s National Security Council staff in 1994, working his way up to writing speeches for the president and eventually leading the NSC’s Europe office.

After Clinton left office, two of his officials, Sandy Berger and James P. Rubin, recommended Blinken for a job with Biden. As chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, Biden was then cementing his role as the leading mainstream Democratic voice on international affairs during the George W. Bush administration’s rush toward Iraq, more statesman than Amtrak Joe. It’s common for the famously emotive Biden to grow close with his aides, but as he and Blinken traveled the world, the senator came to see the staffer as almost like family. Blinken learned to write in the serious but morally concerned voice that Biden — always sensitive about his gaffe-prone, loquacious reputation — had been cultivating. “That relationship of trust developed very quickly. They have similar worldviews and a very similar view of the role of the United States internationally,” said Puneet Talwar, who worked with Blinken for years at Biden’s side. “They have a deep personal bond.” On Iraq, Blinken attempted to push caution. At a time when many were trying to signal seriousness about the repercussions of invasion by planning for “the day after,” Blinken suggested naming the Senate’s August 2002 hearings “The Decade After.” Ultimately, Blinken stuck with his boss in the Democratic middle. He helped Biden propose an alternative to Bush’s plan to invade, before the senator voted to authorize war, which Blinken later characterized as “a vote for tough diplomacy.”

They spent the ensuing years visiting the region and looking for a way out: In 2006, after Biden found himself next to foreign-policy macher Les Gelb on a delayed flight, they hashed out a proposal to split Iraq into autonomous Kurdish, Sunni, and Shiite regions. Blinken helped fashion the idea into a splashy New York Times op-ed. It went nowhere, and before long, Biden agreed to join the ticket of Barack Obama, the candidate who had gained traction in 2008’s election in part by opposing the war from the start.

Blinken was firmly established as a foreign-policy insider by the time he became the VP’s national security adviser. He and his wife, Evan Ryan — a fellow Clinton White House alum turned Biden aide who is now the president’s Cabinet secretary — became known as a genuinely charming D.C. power couple. Blinken played on a Jewish Community Center soccer team with Malley and now-Congressman Tom Malinowski and gigged with bands called Coalition of the Willing, Big Lunch, and Cash Bar Wedding. He has three rock singles on Spotify under the name Ablinken. (Say that stage name out loud.) It was common to hear colleagues say that Blinken has diplomacy “in his blood” — his father was Clinton’s ambassador to Hungary and his uncle the ambassador to Belgium. But, in person, he came across as unentitled and unfailingly polite. A senior Senate aide recalled Blinken as one of maybe two or three people who had ever thanked him, let alone with a handwritten note, after his confirmation.

That reputation served Blinken well in an administration with warring foreign-policy factions. His role was to brief the vice-president and push his thinking, often gathering opposing opinions so they could internally debate them. Before the 2009 inauguration, Blinken joined the vice-president-elect on a trip to Iraq and Afghanistan, reinforcing his skepticism about the latter mission, and he soon helped Biden craft his push to draw down forces more quickly than military leaders and Secretary Clinton preferred.

At times, however, Blinken flashed a more interventionist and idealistic streak than his boss did, arguing for action in Libya, for example, along with then–U.N. Ambassador Susan Rice. The pattern repeated itself in Syria, where Blinken advocated for a forceful retaliation against Bashar al-Assad for his use of chemical weapons — a debate he lost. Eventually, Blinken became Obama’s deputy national security adviser before finally moving to the State Department as John Kerry’s deputy.

None of this was particularly potent fodder for Republicans when Biden nominated Blinken to serve as America’s No. 1 diplomat. The morning of his confirmation hearing, the best the Republican National Committee could come up with was to tag him as “another longtime D.C. Democrat.” Liberals, for their part, did not loudly object to the disclosure that, during the Trump years, Blinken had co-founded WestExec Advisors, a consultancy that worked for corporations like Facebook, Boeing, Uber, SoftBank, and McKinsey on political and international strategies. Blinken earned more than $1 million at the company, which was named after the road running between the West Wing and the Eisenhower Executive Office Building. Federal disclosures showed Blinken had also advised Pine Island Capital, a private-equity fund led by former Merrill Lynch CEO John Thain that, among other things, invested in defense companies. One watchdog, Danielle Brian of the Project on Government Oversight, told the Washington Post in December that Biden aides’ work with WestExec was “disappointing because I thought the message was clear in the past few years that the swamp is unacceptable and it’s time for a change.” But the revolving-door charge didn’t stick to Blinken, who was confirmed with 78 votes, 23 more than he had received six years earlier.

The truth of Blinken’s exile from Trump-era government is that he didn’t go far at all. Almost as soon as Biden left the vice-presidency in 2017, he told friends one of the things he missed most was his access to the presidential daily brief. So Blinken led a group of former aides in delivering a pseudo-PDB, as the session is known, formally presenting Biden updates on the world but without any privileged intelligence assessments. Biden often called allies to fume about Trump. Sometimes, said Delaware senator Chris Coons, a Biden friend, the calls were “just to commiserate, to say, ‘Oh my God, we spent all that time on a detailed and thoughtful strategy on the Northern Triangle’ ” that Trump had discarded. “It was very specific. Sometimes it was as big as “Oh my God, he’s walking away from Paris’; sometimes it was after a NATO summit.”

Blinken stayed close once Biden’s 2020 campaign began, though his home life grew increasingly busy. Both out of government for the first time in years, he and Ryan had two children. Working from D.C. while raising his family, Blinken shaped Biden’s foreign-policy proposals and coordinated with progressive groups who wanted the candidate’s ear. He was one of the few empowered to sign off on big decisions when Biden was unavailable, according to colleagues.

President-elect Biden — himself a three-time almost-contender for secretary of State — tapped Blinken early in the transition. (Coons and Rice were among the also-rans.) Now he’s at the White House as often as four times a week, maintaining what’s often called his “mind meld” with Biden, which ensures that foreign counterparts take Blinken seriously.

Senior administration figures acknowledge there’s a downside to such a close relationship: Blinken’s missteps are seen as Biden’s and vice versa. Both have come in for criticism for declining to directly punish Saudi crown prince Mohammed bin Salman over the murder of journalist Jamal Khashoggi. (Instead, they published a report implicating him and imposed new sanctions on the Kingdom.) “We determined that recalibrating the relationship was hugely important to make sure it was more reflective of our interests and values, but rupturing it was not, in terms of actually being able to advance our values,” Blinken told me a few days after the U.S. released the report. “We’re trying to end the war in Yemen. Are we more likely to be able to do that if we still have a relationship with one of the principal actors or if we don’t?”

Still, wary of repeating the Obama administration’s mistakes — like its frequent semi-public back-and-forth over foreign entanglements — people close to Biden hope the personal and ideological ties between the men will minimize turf wars. Blinken’s friendship with Sullivan, who replaced him as Biden’s top security aide in 2013, will, insiders hope, also help head off traditional schisms between Foggy Bottom and the National Security Council. But, well before Biden has completed his first 100 days, it’s too early to say whether all these good vibes will turn into discord when disagreements inevitably arise. In the past, Blinken and Sullivan have hinted at slightly divergent theories of international change; Sullivan worked closely with the more interventionist Hillary Clinton for years and was widely expected to serve in a senior role, such as national security adviser, in her White House. Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin, meanwhile, has a tight relationship with Biden forged through the president’s late son, Beau, but less of a publicly articulated ideology than his counterparts.

And then there’s Kerry, Blinken’s former boss and Biden’s longtime colleague, now serving as the administration’s climate envoy. Relentlessly deal-hungry as secretary, he has been given a wide-ranging and vague portfolio. So far, he has shied from the spotlight — staying away from Alaska, for example, despite the centrality of climate to the future of Sino-American relations. But Kerry, with no Cabinet-level entourage and therefore fewer COVID restrictions, has recently started traveling too. A day before Blinken touched down in Anchorage, Kerry was photographed on a commercial flight with his mask hanging from his ear, his face exposed. The ensuing PR headache wasn’t just Kerry’s: Both the White House and State had to deal with it too.

Biden’s inauguration had just concluded on January 20 when, across town, a pair of workers pulled down a billboard-size placard from the State Department’s marble lobby. The sign, which had been installed at then-Secretary Mike Pompeo’s behest two years earlier, spelled out a “professional ethos” that read, in part, “We protect the American people and promote their interests and values around the world by leading our nation’s foreign policy.” To outsiders, it looked anodyne, but to many staffers, it was a thinly veiled insult they had been forced to walk past every day; it was condescending, with a hint of a threat against officials who leaked to the press. Now it was gone. “We are confident that our colleagues do not need a reminder of the values we share,” said the department’s new spokesman.

Nowhere in the federal government had the Trump administration’s assault on what he called the “deep state” been more acute, and nowhere in Washington had the evisceration of expertise and confidence been more pronounced. From early in 2017, Trump’s first secretary of State, the former ExxonMobil chief Rex Tillerson, set about “reorganizing” the department through hiring freezes and attempts to force mass attrition. He proposed axing its budget by a third and argued for billions of dollars’ worth of cuts in humanitarian aid as the administration instead emphasized defense spending. Meanwhile, Trump appointees tried weeding out perceived political enemies in the staff. The horror stories quickly became legendary within diplomatic whisper circles. One official of Iranian descent was forced out of a job because Trump allies were convinced she was disloyal; in London, another was fired because he mentioned Obama in a speech. Back home, Tillerson’s staff used an obscure provision of a 40-year-old law to give some ambassadors returning to D.C. from abroad a dismal choice: They could retire or accept a new gig reviewing and declassifying Hillary Clinton’s emails.

The exodus was dramatic. About one-quarter of State’s senior ranks was soon gone, including 14 “career ministers” (the equivalent of three-star generals), 94 “minister counselors,” and 68 “counselors,” according to a Council on Foreign Relations report. Other officials, hoping to wait out Trump from a safe distance, fled their posts for the department’s foreign-language training program. Soon, for the first time since World War II, the U.S. could no longer boast the globe’s largest diplomatic presence, ceding the distinction to China.

Staffing levels kept falling as conditions worsened for career State officials reporting to partisan Trump allies. One ambassador, in Iceland, fired seven deputies. Another, in South Africa, refused to quarantine last year after returning from Mar-a-Lago, then demanded staffers sit in the same room as her for meetings. “The State Department is increasingly run by unqualified donors and political sycophants,” concluded Joaquin Castro, who sits on the House Foreign Affairs Committee, in a Foreign Affairs essay. This flight of seasoned staffers combined with a precipitous drop in applications to the foreign service, exacerbating the department’s generations-old reputation for being “pale, male, and Yale.” A November report written by a trio of veteran diplomats for Harvard’s Belfer Center found that the foreign service looked nothing like the country it represents: By last year, only 4 percent of senior officers were Black. According to data shared with me by Eric Rubin, the former ambassador to Bulgaria who leads the American Foreign Service Association, the officers union, the senior foreign service was 87 percent white and two-thirds male.

Tillerson’s 2018 departure did not slow the department’s deterioration. His successor, Pompeo, a blustery Koch-brothers project who had been leading the CIA after an undistinguished stint in Congress, embraced the chance to get closer to both Trump and the spotlight. He stood by during Trump’s first impeachment as the president tried to discredit career State officials working on Ukrainian issues as embedded opposition operatives, and he spoke publicly in favor of force over diplomacy, almost persuading Trump to strike Iran in 2019. Chatter about Pompeo’s political future was common among career State staffers. Even after rejecting Mitch McConnell’s pleas to run for an open Senate seat in Kansas last summer, Pompeo hosted a series of private dinners with donors, allies, and campaign strategists on the eighth floor of the State Department building; his use of agency resources for his and his wife’s personal purposes became the subject of a whistle-blower complaint and an internal investigation.

Frustration with Pompeo boiled over in his final days in the form of two “dissent cables” signed by hundreds of department officials after he took his time condemning the January 6 Capitol riot. Pompeo had supported Trump’s desperate election-fraud lies; the siege occurred well into a flood of actions he had undertaken to tie the new administration’s hands — such as declaring Yemen’s Houthis a terror group and labeling Cuba a state sponsor of terrorism — and the bizarre barrage of hundreds of valedictory tweets he started unleashing on New Year’s Day. One, sent just hours ahead of Trump’s second impeachment, suggested the president deserved a Nobel Peace Prize. Increasingly isolated, Pompeo canceled his final trip to Europe after officials from Luxembourg refused to meet with him. A few weeks later, a Trump-appointed State official was arrested by the FBI for his role in the insurrection. He had jammed a riot shield into Capitol doors the police were trying to close while yelling for reinforcements from the mob.

The relief among State’s career officials was palpable, if provisional, when Blinken arrived and began taking care of elementary management: reinstituting regular staff meetings; meeting with unions; saying he would advocate for more funding from Congress, not less. He stacked his closest ring of aides with State veterans. Biden helped by returning the U.N. ambassador to the Cabinet (Trump had demoted the role), naming a respected diplomat, Linda Thomas-Greenfield, to the job, then installing another, William Burns, at the CIA. The new president’s first trip to any agency was to State, where he singled out a foreign-service officer for praise while lauding those staffers who had stuck with their jobs. “You’re among the brightest, most involved, best-educated group of people America has to offer,” he said. “In our administration, you’re going to be trusted, and you’re going to be empowered.”

Lest Blinken be accused of pandering to the downtrodden, he has a history of incorporating rank-and-file policy experts into his daily work. Ben Chang, a former State and National Security Council official, recalls Blinken urging him to take a seat at the center table in the White House Situation Room during one Obama-era meeting, insisting, “You’re the expert. This is where you belong.” Under Kerry, Blinken made his first stop as deputy secretary a lunch with foreign-service officers in the employee cafeteria, and he often took junior aides stationed abroad out to dinner. Now, according to people familiar with the interactions, he has asked for his briefings to be delivered by desk officers, not their assistant-secretary or office-director bosses, ahead of his meetings with foreign counterparts.

Yet, two months into the job, few of Blinken’s top deputies have been confirmed by the Senate, and the department still faces both a significant staffing deficit and serious questions about its internal direction. Blinken created, but hasn’t yet filled, the position of chief diversity-and-inclusion officer. And there’s a rift between workers who stayed with the department through the worst of the Trump years and those who left but now want to come back, competing for ambassadorships and other prime gigs.

Meanwhile, everyone is aware that their time may be limited. Hours after Biden was inaugurated, Pompeo tweeted, “1,384 days” — the length of time before the 2024 election. Even if Trump doesn’t run again, Pompeo himself may; he recently headlined a conservative club’s breakfast meeting in Iowa and made plans to beam into a Republican fund-raiser in New Hampshire. After the blowup in Anchorage, he resumed his countdown: “1,327 days.”

When Blinken and I first Zoomed, he had been in the job for six weeks and, thanks to the pandemic, had yet to leave Washington. He was sitting in front of a bland gray wall, flanked by two flags, staring at a screen instead of deploying the kind of diplomacy he knows best and with which he has been most effective: the in-person hand-grabbing, schmoozing, and eye-to-eye confrontation he honed under Biden, who likes to say foreign policy “is a logical extension of personal relationships.” Blinken had sat for roughly 70 video and phone calls with other countries’ leaders and foreign ministers. One greeted him with a cry of “How are you, my dear friend?” Another told Blinken he had “waited 30 years” for the call. This is the easy part of the job — reengaging with eager and exhausted allies while rejoining international pledges and institutions that Trump had deserted, like the World Health Organization, the U.N. Human Rights Council, and the Paris climate accords.

For some nations, Biden and Blinken’s promise to return to a consistent, recognizable policy-making order has been enough to welcome them enthusiastically, but suspicion lingers even among their closest partners. Gallup recently found that approval of American leadership had hit historic lows in countries across Europe (in Germany, it’s 6 percent). The same day Biden declared America’s return during a virtual meeting of the Munich Security Conference in February, Emmanuel Macron promoted the notion of European “strategic autonomy,” and Angela Merkel welcomed him but made a point of noting that “our interests will not always converge,” as the Americans reregistered their opposition to a pipeline between Russia and Germany. “Many allies are delighted to have a like-minded, consensual, principled government in Washington that wants to work with them rather than act unilaterally,” said Peter Westmacott, a former British ambassador to the U.S. “But even some of America’s closest allies are saying, ‘You know what? America always looked after its own interests. We’ve got to find ways of looking after our own which don’t mean always relying, or being dependent, on Washington.’ Maybe that’s not an unhealthy basis for future policy-making.”

Blinken insisted to me that he has no interest in merely rewinding American foreign policy back to the pre-Trump era — and that he couldn’t do it even if he wanted to. “This is not simply pretending the last four years didn’t exist; it’s not starting the machine again where it left off in 2016 or where it started off in 2009,” he said. He characterized the moment as an inflection point. Part of his task is to make the Biden administration’s foreign policy less of an elite sport, translating it for everyday Americans, instead of maintaining its status as an abstraction meant for people who still read the international pages in print. “It’s something the president feels really strongly. He’s said — I don’t know how many times I’ve heard him say it in the years that I’ve worked for him — that no foreign policy can be sustained without the informed consent of the American people,” Blinken said. “Well, we’re about, in a very focused way, trying to get that informed consent.” In practice, that would mean making moves with more of a mind to the homeland and then explaining them in a higher-profile, more digestible way: This deal will lower the cost of your equipment, which will bring jobs back to your factory; renegotiating this alliance will make your food more affordable; giving other countries vaccines will end the pandemic sooner so you can send your kid back to school. “There’s an obligation on us,” Blinken said, “to look at all of this with a fresh set of eyes.”

One of his first orders of internal business was to arrange a series of deep-dive meetings in which he gathers a rotating cast of advisers to reconsider issues in which circumstances have shifted significantly in the past four years. At each session, he asks for a wide range of opinions about what’s likely to happen next for the matter at hand — recent topics have included Iran, migration, “Havana Syndrome,” American hostages, and embassy security — and possible policy directions. And in each meeting, Blinken has asked his aides to consider how one particular variable factors into the day’s given topic: “China, China, China, and, if you have time, China,” said one senior official. “It’s central to everything we’re trying to do.”

In Anchorage, after two days of discussions with the Chinese delegation, Blinken emerged from the Captain Cook and climbed into an SUV for a motorcade ride to the airport. The immediate news coverage was fairly shocked in tone, but I observed aloud that he didn’t seem surprised with how the public portion had gone. “Well, you know — no, not surprised,” he said, shrugging. He had assumed China would be defensive, he said, but once Yang responded as he did, Blinken wanted to make the point “more than implicitly” that the United States deals with its problems openly, “exactly the opposite of what you do.”

Blinken leaned forward as we sped toward Ted Stevens international airport. “One of the things I tried to lay out was we’ve made a major investment over many, many decades and many generations in this infamous rules-based international order. But we did that based on the hard lessons we learned after pulling back after World War I and then, after World War II, making these investments and actually binding ourselves to the same rules that others were under,” he said. “In the aggregate, we think it accomplished what it set out to do: no more Great Power wars and a more predictable overall environment, which other countries — like China — used to grow.”

He got more solemn again as the exit neared. “So I said we have a real investment in this. And the reason we come at you on some of these issues is not only from a rights and moral perspective — although we believe that deeply — but also because, relatedly, a lot of these things reflect commitments that you’ve made that you’re violating. You made a commitment to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights; if you’re violating that, and that happens with impunity, then the edifice starts to crumble. And similarly, on Hong Kong, the commitments you made during the handover were actually enshrined at the United Nations as a treaty,” he continued. “Well, if you’re reneging on that — and this is something that’s good through 2047 — then that undermines the rules-based order that we believe in.”

Blinken’s first trip as secretary was coming to a close as we approached the runway. Three days later, he would be back in the air en route to Brussels, just as Russia’s foreign minister was due in Beijing to discuss what had happened in Anchorage. I asked how the trip matched up with his expectations, and he thought for a second. He had traveled plenty as deputy secretary, he said, but added, “I’ll tell you, the biggest single difference from last time is I’ve got a 2-year-old and a 1-year-old. There’s a little bit of a pang, I’ve gotta say. This is the longest time I’ve been away from my kids since I’ve had them.” The SUV pulled up to Blinken’s plane, and he stepped out onto the vast, mountain-ringed tarmac.