This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

Maya Wiley’s parents, both activists, raised her and her brother, Dan, to be resilient. In 1973, when Maya was 9 and her brother 10, their father, George Wiley, bought a small boat. On their first day out on Chesapeake Bay, he insisted that his children learn how to drive it and drop the anchor in case they ever encountered an emergency.

The next day, Maya and Dan went out with him again. As their father, a big and exuberant man, traversed a narrow wooden walkway on his new boat, the rusted screws holding the walkway in place gave way and he fell backward into the water. His life preserver ripped, and Wiley remembers seeing it float away. She and her brother tried to circle the boat around him to no avail, and they watched him drown.

The siblings managed to drive the boat close enough to shore to drop anchor and swam in to a white beach community, where they ran screaming from house to house and were rebuffed by the first family they tried before someone finally took them in and called the police.

Maya Wiley’s mother, Wretha, insisted that her kids talk about their father’s death, actively encouraging the adults in their lives not to treat it as a taboo topic.

“I think she was right that if we weren’t talking about it, it was going to do more damage,” Wiley told me. Wretha brought her children to her final meeting with the Coast Guard, ensuring they were given their own copy of the investigation report. “She made sure we heard it: that we would be dead if we had driven the boat next to him and he had tried to climb in, because he was too big. He would have capsized it.”

“We were just little kids,” Wiley said, “but she wanted us to hear that it wasn’t our fault.”

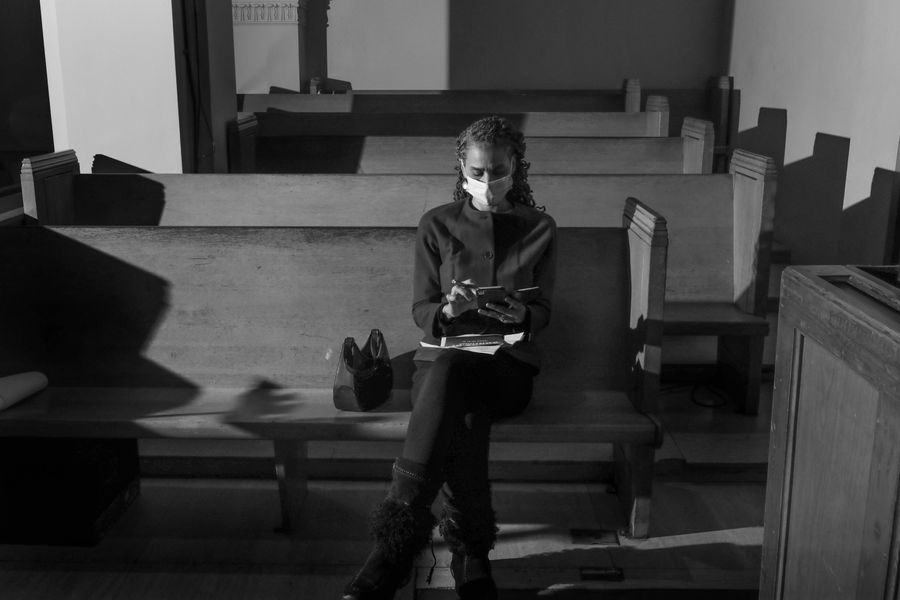

Wiley believes in talking about hard things. Though she hasn’t often discussed this painful story publicly, she did tell it when she launched her campaign for New York City mayor in October. The conviction that her mother instilled in her, that what we don’t address directly will only fester and worsen, seems to undergird Wiley’s campaign to lead a city in the midst of its own trauma. Just four months before the June 22 Democratic primary, the pandemic rages on; restaurants and schools open and shut, doing economic and emotional damage with every swing of their doors; 1.4 million residents face eviction; some wealthy New Yorkers are profiting from the catastrophe; many have died, many more have left.

Wiley is a civil-rights activist, lawyer, New School professor, and MSNBC pundit who served as legal counsel to Mayor Bill de Blasio from 2014 to 2016. As she prepared to enter the race, her path appeared straightforward. In any other election year, her candidacy — as a nationally recognized activist with a career focused on race, poverty, and police reform — would have been seen as practically radical. But in post-AOC, post–George Floyd New York, with a field of more than 30 candidates, at least 14 of whom are ostensibly serious about becoming mayor, several are running alongside her or to her left, and one of them, Comptroller Scott Stringer, has already wrapped up endorsements from many of the city’s insurgent politicians.

With the left lane clogged, Wiley is presenting her identity as a progressive asset. She is a 57-year-old Black woman vying to govern a city that, over centuries, with the exception of David Dinkins, has elected white men to preside over it. In January, her campaign stated that she had met the fundraising match that would unlock $2.2 million in public funding; it would have made her the only woman to have done so. (Her campaign claimed that she’d raised $715,000 overall, with at least $280,000 of that qualifying as match-eligible — $30,000 more than the $250,000 threshold the city requires). But on February 16, New York’s Campaign Finance Board announced that Wiley had not in fact qualified, and as of publication, her team was not immediately clear on what the filing discrepancies were. Wiley will have a chance to correct documentation and receive funds in mid-March, when other candidates, including nonprofit CEO Dianne Morales and former Sanitation commissioner Kathryn Garcia, will also have the chance to make the match. But as it stands, without Wiley’s match, there are no women in the top funding tier of New York City’s mayoral race.

Some of her messaging around identity is blunt. (In January, she introduced a Black Women for Maya initiative with celebrities, including Yvette Nicole Brown and Gabrielle Union; Wiley recently told the Grio that “Black women have been delivering for this country for generations … yet we are always seen as the mules and never the precious cargo.”) But some of it is subtler, informed by her experience as a Black woman who has traversed disparate spaces — Black and white, rich and poor, activist and political — while forcing the kinds of frank, difficult exchanges she sees as crucial to fixing what has been broken and unjust in New York since long before COVID.

In a series of Zoom conversations throughout the winter, Wiley spoke to me from her home in Ditmas Park, where she has lived for 20 years with her partner, Harlan Mandel, who is white and works as an investment-fund manager, and their two daughters, Kai, 17, and Naja, 20. Behind her, I could see rows of bookshelves and wainscoting on the walls; it looked homey, lived in. Twice, she sat in front of a striking painting by the artist Michael Platt, which shows a young Black boy at the edge of an expanse of water. It was a gift from Wiley’s mother.

Sometimes we discussed what we were watching (she and Mandel would settle in for The Mandalorian every Friday night) and what we were eating. (“I’m the get-it-done-because-we-got-to-eat cook,” she said. “He’s the I’m-going-to-preserve-lemons cook.”) One-on-one, Wiley is funny and foulmouthed, vivid in her recollections, and more open than many first-time politicians, who are typically tight-lipped. From time to time during our calls, one or more of Wiley’s three cats (Romeo, Maxie, Bastet) would slink into view as their owner told me how she came to run for mayor of New York.

In the spring of 2019, while Wiley was working at the New School, a group of “heavy-hitter” business leaders asked her to share her view on the upcoming mayoral contest. Implicitly, she said, they were “trying to understand: How did we get a de Blasio?” and she spoke to them about issues like affordable housing until, eventually, one of them asked her if she was going to run. “He wasn’t saying he would support me,” she said. “He was like, ‘You should be thinking about it.’ ”

That Wiley’s mayoral origin story begins with corporate bigwigs planting the seed isn’t as weird as it sounds. She has spent her professional life weaving through spheres of privilege, studying at Ivy League schools and working at foundations, universities, and cable news networks; it’s not surprising that — especially at a moment when protest culture regularly bangs up against prep-school culture — she would appeal to those who, as one elected official described to me, “may be more naturally interested in a Bloomberg, business-first person but who understand that some version of inclusive and more equal growth is the city’s only path forward.”

Expressive fluidity — the ability to talk to anyone about anything — is part of Wiley’s theoretical appeal: Her unusual path to politics situates her as a potentially connective figure between disparate and often noncommunicative city interests.

As a guest on Ari Melber’s MSNBC show in 2018, she gently told the spiraling former Trump aide Sam Nunberg that he should cooperate with Robert Mueller’s subpoena since refusing to do so would make him look guilty and his family would prefer him at home, not in jail, for Thanksgiving. As she was speaking to him, Wiley said, she thought she might be ending her television career. “I was thinking, I’m not doing what I’m supposed to do. I’m not being dispassionate. But I was just like, Fuck it, this guy is going down the tubes.” The exchange went viral, and Nunberg tells me he still thinks fondly of Wiley.

“What she did with Sam Nunberg was what she does every day with a variety of people,” said Rachel Noerdlinger, a partner at Mercury, a public-strategy firm, who worked with Wiley in the de Blasio administration. “She’ll talk to a homeless person and the CEO of Apple with the same respect and openness.” But Noerdlinger told me she also wonders, “How do you utilize that skill to manage a city in turmoil? Is being humanist enough?”

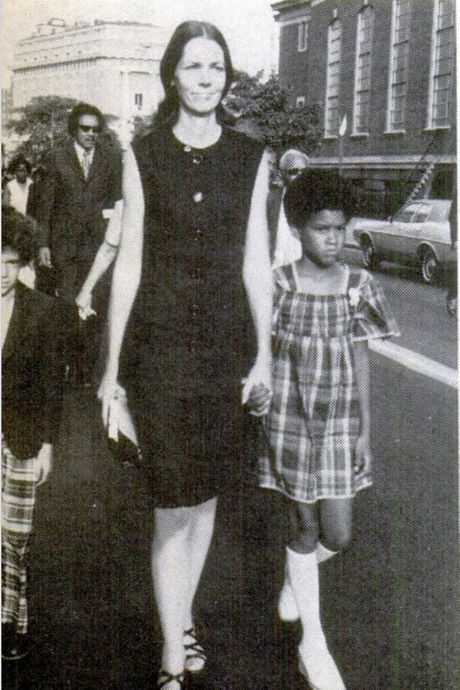

Wiley grew up in Washington, D.C, in the gentrifying but still Black neighborhood north of Dupont Circle, and attended an underfunded public school. Her father, George, who was Black, was the son of a postal clerk; he earned his Ph.D. in organic chemistry from Cornell in 1957 and worked as an associate director of CORE (the Congress of Racial Equality) before co-founding the National Welfare Rights Organization. Wiley’s mother, Wretha, a white woman from Abilene, Texas, was arrested while fighting to integrate schools and later became involved in third-party politics as a supporter of Dr. Spock’s pacifist campaign for president in 1972 and as the environmentalist Barry Commoner’s vice-presidential alternate on the Ohio ballot in 1980. After George’s death, the family moved into a white upper-middle-class area (Wretha would go on to marry another civil-rights activist, D. Bruce Hanson, who was white). Maya left her public school and was enrolled in a private one. It was a wrenching series of transitions for her.

She eventually craved distance from her family’s activist legacy. “I was going to college,” she said. “But to be, like, a psychologist, wanting to help people but also just kind of not being my parents.”

Rebellions sometimes take funny forms. Wiley wound up at Dartmouth in the ’80s. In her first week on campus, a conservative student paper published an anti-affirmative-action piece titled “I Be’s a Black Student at Dartmouth,” which was written in Ebonics. Perhaps it’s no surprise, then, that by the time Wiley decided to go to law school at Columbia, she was determined to work at the NAACP Legal Defense Fund. “I thought I’d be at LDF for my career,” she said, “figuring out the 21st-century Thurgood Marshall strategy, making change at the intersection of race and poverty.”

But in 1993, Bill Clinton appointed Janet Reno to become the first female attorney general, and Mary Jo White became the first female U.S. Attorney in the Southern District of New York. White tapped Jane Booth to be the first woman to head the civil division there; Booth, who had worked with Wiley on a lawsuit against St. Luke’s–Roosevelt Hospital for eliminating maternal and NICU beds in Harlem, recruited Wiley to join her.

Wiley was wary of working in government, she said, but felt it was a “meaningful opportunity” to use the weight of the office on civil-rights cases. Plus she was entranced by some of the cascading representational shifts of the Clinton era: “All these women, you know?”

It was not anything like the opportunity she had imagined. Wiley found herself the only Black attorney out of the group of 50 in the Civil Division and felt that she was not being given the kinds of cases she had been promised, nor the same caliber of assignments as her white peers who had been there for a comparable period. When she’d worked there nearly a year, she told her bosses directly about her frustrations but they said that she simply wasn’t ready.

“I stormed out of the office,” Wiley said. “I was like, ‘This is madness, and I can just take my butt right back to the NAACP Legal Defense Fund.’ I am literally cussing at my desk with my door open and loud. One of my next-door neighbors, who, of course, were all white, comes in and goes, ‘What happened?’ I just let rip because I didn’t care; I was going to quit. Then my neighbor from the other side comes around and goes, ‘What’s happening?’ And the first one goes, ‘Shut the door,’ and I start ranting louder.” Her white colleagues began to ask her to second-seat their trials. “Then all of a sudden, [the bosses] were like, ‘You’re really good.’ ”

Wiley served at the U.S. Attorney’s Office for three years; she stayed mad, but she stayed. “My whole thing was ‘Y’all are going to be sad when I quit.’ And you know what? They were sad when I quit.”

That job, she said, forced her to reckon with the trade-offs of being inside a power system versus agitating from the outside. Wiley remembered lobbying the Department of Justice to join a nonprofit organization’s civil-rights case that would determine whether the Americans With Disabilities Act could cover zoning issues. This, Wiley said, was the kind of case she had taken the job for. The DOJ said no. As she told this story, her voice quickened. “You know what it was? They were afraid they might lose.”

The failure to have the fight is anathema to Wiley. “The whole point of activism is you try to fight like hell when you know you’re Sisyphus,” she said. “My father famously said, when a friend asked him shortly before he died, ‘George, what’s the end point?’ He said, ‘When nobody else is hungry.’ The friend said, ‘But there’s always going to be poverty,’ and he said, ‘Well, then you never stop fighting.’ ”

“That’s how I grew up,” Wiley said. “Like, hell, if we stopped fighting, we’d still fucking be slaves.”

After she left the U.S. Attorney’s Office, Wiley was burned out. She co-founded the Center for Social Inclusion in 2002 and ran it for 12 years. In 2013, de Blasio won the New York City mayoral election and asked her to come meet with him about criminal-justice reform. “Of course, I wanted him to be successful,” she said. “I did not expect him to offer me a job, let alone counsel to the mayor.”

When she first sat down with de Blasio, she said, “It didn’t take me long to realize that I was going to say yes. It became very clear to me: I like this man. He was smart, he cared, he had his Black wife sitting in there with him. Those things matter, right?”

Some who worked with her at City Hall noted that Wiley’s portfolio was unusually expansive, driven in part by her own appetites. She worked on getting free broadband into public housing; she boosted the Minority- and Women-Owned Enterprise Program from $500 million to $1.6 billion in a year; she helped hammer out the law that reduced the city’s cooperation with ICE.

According to multiple people associated with the administration, de Blasio liked Wiley a lot, responding to a shared intellectual and ideological sensibility, but he probably hired her for the wrong job. Wiley had far less enthusiasm or aptitude for the traditionally scuzzier work of being counsel to the mayor. She wasn’t particularly proficient at advising him through investigations into his fund-raising practices or protecting City Hall employees from FOIL requests. That part of the job culminated in her fashioning an inscrutable, slippery-sounding, ultimately ineffective designation, “agents of the city,” to shield de Blasio associates. Some worry that Wiley’s City Hall tenure signals that, as mayor, she would only want to do the jobs she wanted to do and not the scut work that is part of the gig.

Wiley recalled the start of her experience at City Hall as being everything she had hoped for, especially in the implementation of universal pre-K. “It was an amazing feeling,” she said. “But then came the first little crack.”

De Blasio had asked Wiley to help ensure that his advisers looked like the city of New York, and she recalled a day when the racially diverse senior Cabinet was discussing how to fill pre-K seats and instruct New Yorkers on how to sign up. One person suggested they needed to do outreach in beauty salons; a Black adviser agreed, adding, “And barbershops, because Black men are fathers.”

This contribution, Wiley recalled, was “just steamrolled over.” The conversation moved forward, but Wiley spoke up: “I’m going to ask that we go back a step and listen a little more. The reason we need to look like the city of New York is because we need the cultural competency that comes from that.” In the retelling, Wiley paused for effect: “You would have thought I’d called them all Klansmen.”

“I was like, ‘It’s not a big deal. Let’s just go back to talking about barbershops and acknowledge Black men as parents who care about their fucking children!’ ”

Noerdlinger, who was at the meeting, confirmed Wiley’s version of events and remembered that “the look on Maya’s face was almost disbelief. It was the first time, I think, she saw that what she thought [the administration] was, it wasn’t. Like, ‘If we can’t talk about race, what are we even doing?’ ”

And then, Wiley said, “someone complained to the mayor about me.”

De Blasio hadn’t been in the room, she said, but “I got hauled in to account for my behavior in senior Cabinet and for being divisive.” She responded by asking, “So I can be responsible for making sure we hire [diverse] folks, but they shouldn’t have a voice?’ I literally was like, ‘You do know who you hired, right? You did read my résumé?’ And he’s like, ‘You’re upset.’ I was like, ‘Mm-hmm. Yeah. I am. It’s true. Angry would be a good word.’ Because I’m like, look, I’m George and Wretha’s daughter. I got two things I must do in life: Stay Black and die. Everything else is a choice. Including this job.”

It’s also a choice for Wiley — who has previously remained quiet about the details of her experiences in the de Blasio administration — to tell this story now as she’s working to hit a delicate mark on the campaign trail, positioning herself as someone who worked closely with de Blasio, a mayor who has long been popular with the Black voters she is trying to woo even as he has become widely loathed by the press that covers both him and the race to replace him. Wiley understands the press’s dim view of de Blasio and that she is regularly cast by her opponents as, in her words, “de Blasio 2.0.”

She can sometimes sound like him. During one conversation about the “soul of New York and its people,” she told me, “We need to just tell the truth. We are becoming a white city. We are becoming San Francisco. We are pushing people two and a half hours away to commute in for menial jobs that don’t even allow them to have a decent life.”

I asked her later how her vision of moral and civic clarity is distinct from the tale of two cities de Blasio told eight years ago and what distinguishes her progressive promise from the ones many New Yorkers — fairly or unfairly — blame him for failing to deliver. Is she concerned that, upon hearing her rhetoric, too many voters will think that we have already tried this once and it didn’t work?

“What did we try?” she asked. “Tell me. What did we try? Did the entire progressive movement demonstrate it was ineffective because de Blasio couldn’t lead effectively? Okay, so de Blasio couldn’t lead effectively. What does that have to do with progressivism? And what does every single person praise about the de Blasio administration?”

Universal pre-K, I reply.

“Right,” she said, winding up for the big swing. “That was progressivism. Progressivism didn’t fail. De Blasio failed.”

So far, Wiley’s biggest concrete proposal is her New Deal New York package, modeled on Roosevelt’s Works Progress Administration. Except, unlike the original New Deal, which initially left out agricultural and domestic workers, Wiley’s plan specifically aims its aid toward the city’s most vulnerable residents. It’s a $10 billion recovery proposal that would borrow from the capital construction budget to stimulate the city’s economy, focusing on infrastructure repairs of bridges, tunnels, and NYCHA housing and investing a billion dollars in the arts, climate construction, and job creation.

Siphoning from the capital construction budget is one thing; getting money from Albany is another. “I am a single-issue voter, and my single issue is: Can you get money out of Cuomo or not?” said Monica Klein, a progressive consultant who is not aligned with any mayoral candidate. Speaking of all the contenders, Klein said, “You can put out as many transit plans, housing plans, and education plans as you want. But every plan is bullshit because we are fully broke and Cuomo won’t fund the city. There are breadlines around the block. The only thing that matters is if you can get money out of the State.”

Cuomo is too popular for candidates to easily position as a nemesis, even though, when it comes to New York City thriving, he arguably is one. He has made it clear how much he enjoys toying with the city and dominating the wannabe tough guys, like de Blasio, who run it. Multiple political insiders suggested to me, sotto voce, that this is an avenue where Wiley’s identity may be a real asset. “Cuomo would eat Scott Stringer for breakfast,” said one person who has worked with both men. A different strategist said, “If I were Maya’s City Hall adviser, I would say the greatest strength we have is that Cuomo is scared of Black women.” It is also likely that a deft communicator like Wiley, who has navigated corridors of white male power throughout her career, might find other ways to finesse the relationship, understanding that Cuomo could benefit from the public perception of cooperation with and benevolence toward a city run by a mayor like Wiley.

She called the breakdown between de Blasio and Cuomo “a big, big missed opportunity.” And yeah, she knows the other dynamic, too: “I have no body parts that I need to measure against anyone else’s.”

While multiple major cities have elected Black women mayors in recent years — Muriel Bowser in D.C., Keisha Lance Bottoms in Atlanta, Lori Lightfoot in Chicago — New York, a diverse metropolis that prides itself on forward-looking politics, has not managed to do so. (The one time the city elected a nonwhite man, in 1989, his successor was Rudy Giuliani, chosen in a spasm of vengeful backlash that previewed the rise of Trump.) If, at the end of this race, a year after the BLM protests, a white man once again winds up running the city, it would underline some of the ways in which New York, whatever its sense of exceptionalism, often works as a microcosm of American intolerance and unmet representational promise.

Identity matters in New York City politics. But how, and for whom it works, is the subject of a lot of debate. For example, political strategist Neal Kwatra noted that de Blasio won in part because Black voters took him seriously, “and part of how he was able to make the sale was by presenting his identity as inextricably linked to his family.” But emphasizing identity is riskier in an era when some see any direct play for political office rooted in race or gender as performative or cynical. That doesn’t make it any less real that New York has never elected a woman to lead it, and it doesn’t make it any less irritating that, somehow, the city’s big beneficiary of identity politics before it became uncool was de Blasio, who, married to a Black woman, is still a white man.

Wiley’s campaign is using her identity as a way to leverage some progressive authority. She is competing for Black votes against other Black candidates, including Eric Adams and Ray McGuire, both of whose politics are far more centrist than hers, and Dianne Morales, an Afro-Latina former nonprofit CEO competing with Wiley from the left. “Look, the Black community is diverse,” Wiley said. “We have generational divides. We have class divides. We have parts of the Black community that are fairly centrist, parts that are extremely activist.” She argues that she’s the only candidate who pulls these communities together. “I lived in a low-income Black community, grew up with kids on welfare and with Black folks driving Cadillacs, going to private schools and everything in between. My literal biological aunties are deeply religious. I got it all.”

If this feels forced, it may be because Wiley is unused to framing her heritage in quite such a bald-faced manner. Noerdlinger told me that she urged Wiley to start speaking in a way she hadn’t before about her roots. “I told her, ‘Your father was one of the biggest poverty fighters we’ve had.’ She was uncomfortable because she said she didn’t want to capitalize off that.” At one point, I asked Wiley what her parents would think of her mayoral bid. She said that her mother, who died in 2013, “would be horrified. She thought politics were busted, broken and bad; to get involved in electoral politics as a politician was not something she thought highly of.”

As for white liberal voters, that’s where Wiley’s appearances on television — especially during the Trump era, when many Democrats were glued to MSNBC — come in. She could make a real play for the city’s population of squishy liberals, anxiously wondering Whether or Not There Is a Place for Me, a Nice White Parent, in the Progressive Movement. But there will be a cost for any progressive who cleaves too enthusiastically to them: The young, ascendant left is skeptical of anything that smacks of posturing — for reasons that are both very fair and indubitably gendered. Support that Wiley has already gotten from Alyssa Milano and Rosie O’Donnell may enrich her coffers, but it also risks making her look like a resistance grifter in the eyes of movement activists.

Balancing all these constituencies may be part of what has so far kept Wiley from really owning either an activist stance or a more mainstream liberal one and in turn from getting the attention she will need in a crowded field.

“Men can be bridge candidates,” said Melissa Harris-Perry, the political-science professor and former MSNBC host who appeared in late January at a Black Women for Maya event. “Women have a much harder time, particularly Black women, because the presumption quickly becomes that they are selling out in some way. There isn’t a model of Black women being able to have an insurgent campaign and be ingratiated to power.”

For now, Wiley is holding her own, though the Campaign Finance Board news that she had not met the public-financing match was a major setback, both financially and optically. Her January filing showed her to have more individual donors — at around 6,500 — than any of her competitors, though Andrew Yang entered the race too late to file. Yang, who is well ahead of the pack in what meager polling there has been, is profiting from the kind of national recognition that had been expected to accrue to Wiley. He is also connecting with voters, in this dismal season, as a wacky, frenetic, easy-on-the-brain inverse of de Blasio. As one state party leader told me, “New York wants someone with energy. It’s why Andrew Yang is jumping around and outside. No one else is outside talking to people.” (The day after this conversation, Yang tested positive for COVID).

In a February debate, Wiley lit into Yang: “As a civil-rights lawyer, I was shocked to hear that you have a nondisclosure agreement. That sounds very Trumpian. Will you commit to allowing your campaign staff to complain about workplace misconduct?” It was snappy and aggressive; like Elizabeth Warren grilling Michael Bloomberg on sexual harassment, Wiley had put her lawyerly muscles to contentious use. Gothamist’s coverage of the debate led with the line, calling it “the sharpest jab of the first mayoral debate of the season,” a valuable appraisal in a race in which attention is so scarce and candidates so plentiful that any coverage is precious.

But there is no question that Wiley has not yet made a huge splash in the gurgling mayoral murk. Politico’s Sally Goldenberg has already written a pre-death knell for Wiley’s campaign, noting that she tends to answer questions about crucial issues at length and without specificity. In the New York Times, education reporter Eliza Shapiro has lobbed a similar critique, describing how, despite having co-chaired the School Diversity Advisory Group under de Blasio, Wiley gave “conspicuously broad answers to direct questions” in a recent debate on schools and seemed unwilling to say whether she would end tests for the city’s elite public high schools, something her competitors on the left, including Stringer, Morales, and City Councilmember Carlos Menchaca, all said that they would do.

This isn’t just the challenge of being a bridge. It is also about being the kind of candidate who enjoys weedy nuance and complexity but gets heard, in a political context, as being mealymouthed, waffly, unwilling to take a stand or make a promise to which she will inevitably be held. In her article, Goldenberg reported on a closed-door meeting with union representatives during which Wiley failed to clearly affirm that she would stand on a picket line. “Her brain isn’t wired to quickly pander,” one of Wiley’s communications staff told me. But this is the New York City mayor’s race, and to paraphrase a great New York City movie: When a union representative asks if you would stand on a picket line, you say yes. (Wiley later joined picketers at Hunts Point.)

Wiley’s penchant for winding, intricate exchange also doesn’t lend itself to checking off agenda items, some former colleagues said. “She is not good at running a meeting,” said one. “We would go in circles.” That impression may make it harder to keep pace with her most serious competition, Stringer, who has repeatedly promised he will “manage the hell out of the city.” It’s an unromantic vow, but one that strikes close to the heart of many depleted New Yorkers and exposes a weak spot for Wiley, who doesn’t have a lot of managerial experience.

She pushes back on that characterization: “Lots of people can manage.

That’s not the question. It’s this: Can we reimagine? Knowing how government works is not the same as getting it to work transformationally.”

Stringer certainly knows how government works. He is an exceptionally shrewd politician, one who read the progressive tea leaves after de Blasio’s surprise victory and Ocasio-Cortez’s ousting of Democratic incumbent Joe Crowley in 2018, tacking left and endorsing other insurgent, young progressives (such as Jamaal Bowman, Jessica Ramos, Yuh-Line Niou, Alessandra Biaggi, and Julia Salazar), who in turn have already endorsed him back.

“There’s no question that watching support from progressives — and particularly progressives of color who are women — go to a man is painful,” said Wiley, taking care to say that she’s not referring exclusively to Stringer, even though it’s clear that she is. “If it was philosophical, if it was policy-based, that would be different. But this is not that.”

Wiley may have underestimated how determined Stringer is to overcome what he perceives as a major Achilles’ heel: “It’s awkward to be a white older insider politician,” said one progressive strategist of Stringer (though, in fairness, not that awkward; it still seems to work out okay for a lot of them). “He has lived in fear of a candidate of color to his left forever.”

In December, I began to notice that every time I spoke to someone in Stringer’s orbit, they would respond to the fact that I was profiling Wiley by saying some version of “What about Dianne Morales?”

In mid-January, the progressive Bronx state senator Gustavo Rivera announced he would be endorsing Stringer, which was not a surprise. More surprising was that Rivera was the first prominent city politician, in the new universe of ranked-choice voting, to be making the savvy move of endorsing a second-choice candidate: His was Dianne Morales.

Morales and Stringer both appeared at the outdoor event. There was a podium with a Stringer sign affixed on top and a Morales sign below it. Stringer spoke, joking awkwardly that he was “proud to be here with Dianne” but that “obviously, I don’t want her to be mayor,” while Morales, who also spoke, said Stringer was her “No. 2,” something her campaign later clarified had been a joke.

It seemed possible that Stringer was trying to align with a Black female candidate he perceived as less likely to be a threat to him than Wiley, thereby pitting one Black woman against another. It might have been a misjudgment: Morales’s campaign has picked up steam in recent weeks, after the Rivera endorsement and a bold debate performance that earned her praise in the New York Times. (At a more recent forum, both Morales and Wiley named each other as their No. 2 choices.)

But if it was Stringer’s intention to set up a more visible contrast between Morales and Wiley, he may have succeeded. “Morales has occupied the exact branding space that should have been Maya’s,” said Kwatra. “There is a lot of activist energy flowing to Dianne now that should have been Maya’s to pick up and organize.”

Among the thorniest issues for Wiley — when it comes to harnessing progressive energy, emerging from de Blasio’s shadow, and persuasively articulating her vision for a post-pandemic New York — is police reform. It’s an area in which she has some of the deepest expertise, but her holistic view of the dynamics may be making it harder for her to clarify her messaging.

“I’ve taken heat, sometimes from my friends, for not saying the word defund,” she said. Morales and Menchaca have made that specific call, with Morales suggesting a $3 billion cut to the NYPD budget. (On February 11, Wiley proposed reducing the NYPD by 2,250 to provide yearly grants to 100,000 city caregivers.) Wiley said her own approach is rooted in her thinking about how she might govern as mayor, a job she sees as distinct from the job of advocates, whom she respects and often agrees with.

“I’m the only one who’s actually done it inside,” Wiley said. “Who actually knows how hard it is.” It’s striking that here — on the issue where she has long been an outside expert and activist — she is emphasizing her insider’s vantage point, though she insists she has “always been consistent about right-sizing” the NYPD, which, she says, “means shrinking the number of badges and guns.”

Critics point to her 2016–17 tenure running the Civilian Complaint Review Board, during which she was criticized for not doing more to sharpen a sluggish organization or swiftly bring about the termination of Daniel Pantaleo, the cop who killed Eric Garner in 2014. “The agency was a wreck, a nightmare,” Wiley said of its state when she got there. One colleague agreed that the CCRB is “limited in its authority, and that’s a structural problem. But that’s not a good enough excuse if you’re the one leading it. And it’s not good enough if you’re the mayor. The CCRB should have been louder and bolder during this administration.” (Garner’s mother has endorsed McGuire in this race.)

The Reverend Al Sharpton, who said he doesn’t know if he’ll endorse any of the mayoral candidates, defends Wiley on the question of language and rhetoric, especially around “defunding.” “Her approach reminds me of dynamics we’ve always had in movements,” Sharpton said. “You have those all the way to one side and then you have those that say, ‘How do we get it done?’ Families don’t want a hashtag; they want laws changed, and they want to see their loved ones not killed.”

The question of what substantive police reform (like, for real, in New York City) may look like in 2021 and 2022 — after the Floyd protests and surging pressure to reckon with systemic police misconduct, after years in which de Blasio caved to the NYPD repeatedly, in a city on a financial precipice with violent crime rates rising — is a knotty mess for any of the candidates to take on.

As one New York official told me, “I need to hear, ‘When those 36,000 cops report to me, here’s how I’m going to deal with it.’ The police are going to fight you tooth and nail if you actually try to impose reform. You’re going to have a giant public-safety strike.”

This summer, Wiley was protesting in the streets and considering how she would handle the situation if she were in City Hall. After police plowed into protesters near the Barclays Center and the commissioner praised officers the next day, she said, “He’d have been called right into my office. ”

Given that de Blasio, a white man, has repeatedly deferred to police yet is nonetheless loathed by them, I asked Wiley how she pictures it going when she, a Black woman, openly censures them. “It goes down with integrity,” she said. “I’m sorry, I grew up on a playground where kids were going home saying, ‘Wait, but who got bloodier?’ You don’t get punked.”

Had she been mayor this summer, Wiley said, counterintuitively, that she would have looked for cops to praise for their work to de-escalate conflict. In the wake of Garner’s murder, she actively sought out relationships with officers. Wiley recalls “a white Irish Catholic police officer who said, ‘The public hates us,’ but began describing mistreatment and abusive management practices [they endured].” It was something she heard from many officers. “You have to figure out a way to provide incentives and support for good policing but also good management that’s not abusive.” As mayor, she said, she would find ways to “to lift up, protect, and support police officers who do the right thing.”

Wiley gets that her proposal of elevating good cops and addressing their mistreatment inside the force won’t get her far with the activists with whom she is supposedly aligned. From the community standpoint, she said, “we rightly say, ‘That’s not our problem.’ But from a human standpoint, it is important to understand what it’s like to be beaten up every day inside our job by your managers and sometimes by your fellow officers.”

Those standpoints, however, aren’t always so distinct. In December, the Daily News’s Harry Siegel reported that Wiley and her partner are among those in Ditmas Park who chip in $550 a year to fund a private security car that has been patrolling the neighborhood for 30 years. Wiley told Siegel she hadn’t realized her partner had started paying for the service again, after stopping years earlier, and said she believed the car was “ridiculous.” But, she explained, their familial disagreements around this were complicated by the fact that Mandel was violently mugged in 2001 and beaten badly enough that he was hospitalized. “It’s not necessarily rational, but it is his trauma response, so it’s a complicated one for our family,” she said.

It’s an interesting inversion of de Blasio’s familial dynamics with regard to racism and policing: As a white man with Black children, de Blasio could gain credibility with activists for his insight into the concerns of Black New Yorkers and their experiences with police. Wiley, the Black police reformer, can see, via her white partner, the view of the New Yorker who derives a sense of security from police. It’s a versatility of perspectives she applies to lots of situations, framing it not as conciliation or compromise but as a means to humanely acknowledge and address trauma.

“Trauma is real on all sides,” she said. “So the community is absolutely right to say [to police], ‘I don’t care if your job is hard. When you have a gun and a badge and all this power over me? Your trauma’s not my problem.” But, she says, “governing means that you’re taking that into account and figuring out how to fix it. That’s your job.”

But if she’s increasingly seeing herself on the governing side, Wiley can’t fully shake her identification with outsiders. When I ask about leaders she admires, she responds with the names of activists: Johnnie Tillmon, Beaulah Sanders, the women of the welfare-rights movement with whom her father worked. I push her to name someone inside politics whose leadership style she would want to emulate, but she comes up mostly empty. She will always return, she says, to Shirley Chisholm (whom she refers to several times during our conversations as “a model”) and to FDR and the New Deal, “both in terms of its incredible transformativeness and its race discrimination.” Aside from that, she said, “I’m going to be breaking some governance molds.”

But it’s hard to sell something you don’t yet have a model or a blueprint for. And by way of explanation, she again turns to an activist framework: On Martin Luther King Day, Wiley was preparing to address Sharpton’s National Action Network. “There are so many great King quotes,” she told me, “yet we pull out the same damn quotes every year. I’m pulling out the socialist quotes, the ones that say, ‘If peace means economic exploitation, I am not for peace. If peace means humiliation and segregation, I’m not for peace.’ ” But she’s also thinking of this quote: “ ‘Faith is taking the first step, even when you can’t see the whole staircase.’ Because we can’t see how we get to the end vision all at once.”

We tend to think of New York City as a metropolis built of hard surfaces: the glass and iron of skyscrapers and the steel of subway tracks. Hard lines — polling numbers, pithy slogans, and bracing promises — are also what we tend to value in political campaigns.

In the 2021 mayoral field, there are many sharp vows, shiny and appealing things we’re being promised in the midst of our slushy anxieties: Stringer’s assertion of managerial prowess. Eric Adams’s tough line on crime. Yang’s checks. Morales’s clearly delineated demands to defund a department.

I don’t want to feminize (and thus inherently diminish) Maya Wiley’s approach to the race by calling it soft, but I do think that when she looks at New York City, she doesn’t see the buildings or budget lines but the millions of bodies that inhabit it and the very complex and winding paths those bodies are on. Her view of what comes next is simply not straightforward.

A week after the Capitol siege, she spoke with me about the instability her daughters’ generation feels, noting, “As bad as it was for us, we knew shit was not good, but damn, did we think there was a floor.” She is thinking too about her partner’s family in Germany in the 1930s, forced to make life-and-death choices, how her father-in-law was arrested after Kristallnacht and sent to a concentration camp. “Black people have this too,” she said, “where you’re like, ‘Yeah, shit can go real wrong real fast.’ ”

Thirty candidates are making the case for what New York City definitely needs next from its leadership, and thanks to the breadth of the field and the prospect of ranked-choice voting, many of us are going to find ourselves making mix-and-match guesses about what will be best: experience, experimentation, practicality, idealism, change, steadiness, a comforting past or a different future. We’ll be making those choices in the face of hurricane-level unpredictability.

Here’s Wiley’s argument: that she has had the experience of having been forced to steer through unpredictable currents, professionally, politically, and personally. Or at least that’s how she framed it when she opened her campaign, describing herself and her brother on the boat in the Chesapeake.

“When I think of 24,000 families who could not touch or hold their loved ones, I think of how I could not touch my father or feel him hold me ever again,” she said. “My brother and I, two little kids, alone on deck watching the waves wash away our father. We had to find a way to live. So we had to look each other in the eye, fight back the tears, drive the boat to shore, and find a way home.”

*This article appears in the February 15, 2021, issue of New York Magazine. Subscribe Now!