This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

On the afternoon of January 6, as a horde of Trumpist dead-enders marched from the White House toward Capitol Hill, a contingent of a few hundred stopped roughly midway along the route at the Department of Justice. A bearded man in sunglasses and a red MAGA hat narrated the scene in a video filmed on his cell phone: “In front of the DOJ building with a whole lot of pissed-off people.” The department’s headquarters, known as Main Justice, is constructed out of limestone and features 20-foot Art Deco aluminum doors that slide shut at night. At some point, as the mob massed at the entrance, the night doors closed, making the building impenetrable.

The protesters waved Trump banners, shouting and chanting:

“Do your job!”

“Lock them up!”

“Fuck you! Do your job!”

Do your job … At no point in its history, perhaps, has the mission of the Department of Justice been so difficult, so polarizing, and so critical to democratic stability. President Donald Trump had given his supporters the deluded hope that the department might use its powers to substantiate his fantasy that the 2020 election was stolen. Over the course of the Trump administration, Democrats had demanded investigations of the president and his cronies, while Republicans countered with their own investigations of the investigators. The fact that one side was reasonable and the other maniacal did not diminish the reality that the dynamic — the politicization of prosecution — was poisonous to the workings of justice.

By the time Trump’s supporters arrived at Main Justice, the institution was already buckling under political pressure. Many of the department’s career civil servants had been working at home during the pandemic, at times leaving Trump’s appointees almost alone in the building. Attorney General William Barr had resigned, his loyalty finally overwhelmed by the president’s lunacy. Now Trump was badgering the interim AG, Jeffrey Rosen, to appoint a special prosecutor and ask the Supreme Court for a do-over election in six of the states he lost. Trump’s chief of staff was forwarding links to a YouTube conspiracist who suggested that Italy had used military satellites to remotely rig the election for Joe Biden. When Rosen refused to cooperate, Trump schemed to replace him with an amenable deputy. At a January 3 meeting in the Oval Office, Rosen and the deputy struggled over the job in front of Trump, and senior Justice officials threatened to resign en masse. The following day, military leaders convened a conference call with members of the Cabinet, and the acting Defense secretary advised that extremists were plotting to make January 6 a “pretty dramatic day.”

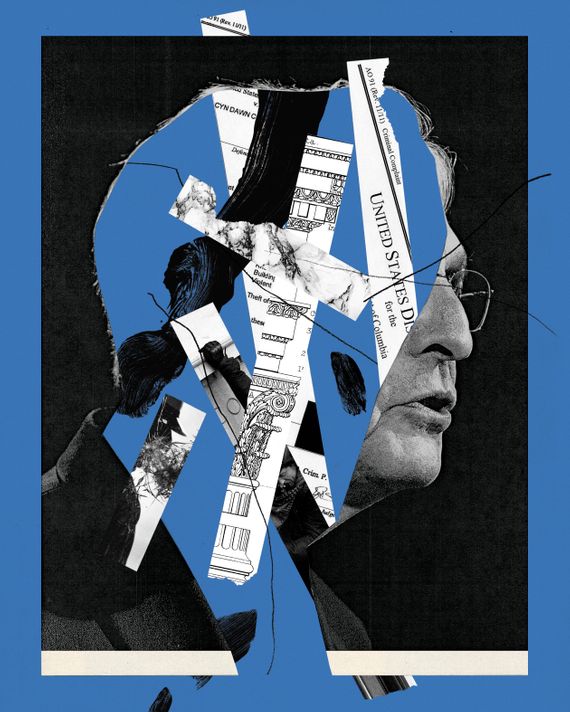

A few minutes after noon, as Trump was whipping his crowd into a frenzy, Politico broke the news that Biden had picked Judge Merrick Garland to be the next attorney general. To most Americans, Garland was known for one thing: his 2016 nomination to the Supreme Court, which was strangled by Republicans. The notion that an infamous victim of Trump-era partisanship might end up as Biden’s AG had a whiff of cosmic justice. “That’s a badass move,” tweeted David Corn, one of many prominent liberals delighted by the news. “I can barely control my happiness,” Joy Behar posted. “Irony,” Rob Reiner added, “thy name is Merrick Garland.”

The 68-year-old judge was at home in Bethesda, Maryland, preparing his remarks for an introductory press conference with Biden to be held the next day. But soon the news of his selection was overshadowed by the violent spectacle of rioters storming the Capitol. Right-wing extremism, as it happens, was something for which Garland was well prepared: Before he became a judge, he made his career as the top Justice official overseeing the investigation of the 1995 bombing of a federal building in Oklahoma City, the deadliest domestic terror attack in American history.

On January 7 in Wilmington, Delaware, Biden made an implicit reference to this newly relevant aspect of Garland’s experience. “What we witnessed yesterday,” the incoming president said, “was not dissent. It was not disorder. It was not protest. It was chaos. They weren’t protesters. Don’t dare call them protesters. They were a riotous mob. Insurrectionists. Domestic terrorists. It’s that basic.”

When Garland came to the podium, though, he spoke in a more cautious register. He referenced Edward Levi, the Republican attorney general who stabilized the DOJ after Watergate, reestablishing the “independence of the department from partisan influence.” He talked about norms, regulations, and prosecutorial discretion. “As everyone who watched yesterday’s events in Washington now understands,” Garland said, “the rule of law is not just some lawyer’s turn of phrase; it is the very foundation of our democracy. The essence of the rule of law is that like cases are treated alike — that there not be one rule for Democrats and another for Republicans, one rule for friends, another for foes, one rule for the powerful, another for the powerless.”

After four years of nearly existential struggle over the Department of Justice, Garland was striking a note of refreshing equanimity. Democrats breathed a decompressing sigh: sanity. It was only later that they realized, to their frustration, that his idea of justice might not deliver the reckoning they desire.

In the months since the Capitol was breached, the Justice Department has waged one of the most extensive prosecutions in the nation’s history. More than 500 Trump supporters have been arrested on charges ranging from trespassing to criminal conspiracy. For a flicker, it seemed as if an attack on Congress itself might be the outrage that united the parties. Garland breezed through his confirmation hearings, during which Republicans assured him that their opposition to his Supreme Court nomination had been nothing personal.

But the moment quickly dissipated. Those same Republicans later stymied a proposal for an independent bipartisan commission to investigate January 6, leaving it to others to mete out piecemeal accountability. (On June 30, the House voted along party lines to authorize a probe led by Democrats.) It is Garland, and his Justice Department, who will likely have the greatest say about the most shocking and visible crime of the Trump era. Though the entire country witnessed it on television, the meaning of the event remains unsettled. Was the assault a protest that got out of control? Or had some of the zip-tie-wielding crew really been intent on stringing up elected officials and initiating a coup? In the heated aftermath, federal prosecutors raised the possibility of charging leaders of the mob with seditious conspiracy — an archaic crime of rebellion. It sounded draconian, but if attacking the Capitol wasn’t sedition, then what was?

Garland has gone about his task with extreme delicacy. On his first day, he gave a well-received speech to his staff, pledging to “adhere to the norms that have become part of the DNA of every Justice Department employee.” Since then, he has scarcely said anything of substance about January 6. “In my career as a judge and in law enforcement, I have not seen a more dangerous threat to democracy than the invasion of the Capitol,” he testified before a Senate committee. In mid-June, as part of a broader Biden administration initiative, Garland unveiled a $100 million program to police domestic terrorism. But when pressed to say how he plans to address January 6 itself, he tends to reply obliquely, often referencing his history with Oklahoma City and an earlier form of right-wing extremism.

Garland’s first major public appearance as attorney general came on April 19, when he returned to the city to speak at a memorial service. His choice of venue seemed intended to send a message: He had been here before, and so had America. It had been exactly 26 years since a decorated Gulf War veteran named Timothy McVeigh detonated a truck bomb outside the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building, killing 168 people, including 19 children. The commemoration at the site, now a national memorial, brought together survivors, first responders, and families of the victims. The day was breezy, and the atmosphere was intimate. Garland walked in a procession to a stage on the far side of the reflecting pool that runs down the center of the memorial. Over his shoulder were 168 sculpted chairs, decked with flowers, photos, and, for some of the children, stuffed animals.

As a crime, the mass murder was categorically different from the attack on the Capitol, but the beliefs that motivated McVeigh were eerily similar. He was a conspiracy theorist who believed that the “new world order,” an all-powerful deep-state cabal, was conniving to impose a global dictatorship. He was fanatical about the Second Amendment and lived on the gun-show circuit, peddling copies of a racist novel. He had ties to a Michigan militia. In 1993, McVeigh drove to Waco, Texas, to protest during the standoff between federal agents and a heavily armed cult. After the siege ended in an inferno, he decided to build his bomb. He called himself a patriot.

In the conventional telling, McVeigh’s act marked the culmination of a period of right-wing radicalism, creating a backlash that discredited his cause. But onstage in Oklahoma City, Garland witnessed firsthand how the bombing has since become yet another point of contention in the culture wars. The first officeholder to speak was Mayor David Holt, an anti-Trump Republican, who warned that “we here in Oklahoma City have a special understanding of what inevitably ensues when words of division and dehumanization are uttered and when lies are spread.” He was followed by Governor Kevin Stitt, a staunch Trump supporter, who offered a contrary interpretation: “Never in our lifetime has it been easier for us to be divided. There are groups that refuse to listen to another point of view. They try to cancel anyone who sees the world differently.”

Then Garland, who had been sitting impassively, came forward. He is brittle-looking, with a papery complexion and a downturned mouth. “Every year on this day, wherever I am, I reflect on the loss so many of you endured,” he began, his voice quavering, “the loss you continue to endure.” Then he told his version of the Oklahoma City story.

On April 19, 1995, Garland was sitting in his office at Main Justice, reading email — then still something of a novelty — when a message appeared with the subject line URGENT REPORT. Soon, CNN was broadcasting live footage of the destroyed Murrah building. Garland volunteered to oversee the investigation. Landing in Oklahoma two days after the explosion, he headed straight to a hearing for the freshly arrested McVeigh, then to the scene of the crime. It was nighttime, and floodlights were blazing. Rescue workers with dogs were searching for survivors. Garland took a still-functioning elevator to an upper floor and walked into an office. There were papers and a can of Coke on a desk, a coat was draped over a chair, then there was open air.

At the time, no one knew for certain if McVeigh had acted alone, and there was intense pressure to discover collaborators. Garland worried that the urgency might cause mistakes that would later hinder prosecution. He knew that the horror of the moment would diminish by the time the case went to trial. “Several years after,” he later said, “very bad crimes look different.” If the conspiracy investigation looked like an indiscriminate roundup, it might even end up changing the political context, bolstering the very ideology that motivated McVeigh.

Ultimately, prosecutors agreed that McVeigh acted with significant assistance from only one other conspirator, Terry Nichols. Garland oversaw the negotiation of a deal with a married couple who were also aware of McVeigh’s plan: In exchange for becoming star witnesses, the husband got a plea bargain and his wife wasn’t charged. Two of the primary FBI agents on the case would later call the arrangement “sickening” but justified.

Garland wanted to try the cases personally and was dismayed when Attorney General Janet Reno said she needed him in D.C. But he continued to oversee things from Washington. The gaudy spectacle of the O. J. Simpson trial was under way in Los Angeles, and Garland told the prosecutors to keep the proceedings simple, setting aside all but the most damning evidence. “Do not bury the crime in the clutter,” he said. The lead prosecutor wrote the phrase on a sign and hung it in the office. (It is today in the Oklahoma City National Memorial & Museum.)

McVeigh was convicted and executed. But a jury declined to convict Nichols on the most serious charges and deadlocked over whether to impose the death penalty. (He’s now serving a life sentence.) Over time, their extremist ideology appeared to fade, and the militias disbanded, although it was never clear whether law enforcement could take the credit. “Was it successful, or did it go back underground?” asks Donna Bucella, a former DOJ official who worked closely with Garland on the Oklahoma City case. As the number of militias dropped, there was a corresponding rise in the number of white-supremacist hate groups.

Michael German, a former undercover FBI agent who is a fellow at the Brennan Center for Justice, says some militant groups simply refocused on immigration and rebranded as “border patrols.” After 9/11, the FBI shifted its attention to international terrorism. “There’s an institutional bias that white-supremacist violence is not that big a deal,” German says. “It’s a bunch of stupid rednecks, and it’s not any kind of coordinated threat.”

Then the explosion of social-media networks brought extremist groups to the fore again. At Charlottesville in 2017, they displayed their new, youthful, rage-filled face, and 2020’s summer of protest gave them an opportunity to take their fight to the streets. During a presidential debate, Trump told the Proud Boys to “stand back and stand by.” The movement had risen again — this time, with the president at its front.

In his every public utterance, Garland has conveyed that he is an institutionalist — someone who believes his project is to extract the Justice Department from the maelstrom unleashed by Trump. In a time of flagrant boundary violations, he is a rule-maker and a rule follower, a decorous man in an indecorous age. “He is conservative — not in the political sense,” says Seth Waxman, a friend from college and a fellow DOJ veteran. “He has a very high sense of propriety, and I am tempted to say that Merrick is a cautious person. Very, very careful and very, very thoughtful and discerning.”

Garland is also an insider — a Washington lifer with deep connections to the Democratic Establishment. The first item on his CV is a summer job on the campaign of Abner Mikva, a Chicago congressman who became an appellate judge and a mentor to Barack Obama. His wife is the granddaughter of the FDR adviser who coined the phrase “The New Deal.” Garland went to Harvard and Harvard Law and clerked for the liberal Supreme Court justice William Brennan. Although he did a stint as a prosecutor, he rose through the ranks at Justice on his talents as an administrator. According to Main Justice, a Reno-era book about the department, Garland was regarded within the building as a “type triple-A personality.”

After Garland’s success in Oklahoma City, President Bill Clinton tapped him to replace Mikva on the court of appeals for the District of Columbia. But Republicans held up Garland’s nomination for more than a year, an obstructionist move that was condemned by the ranking Judiciary Committee Democrat, Joe Biden, as “malarkey.” Garland kept his head down at Main Justice, and eventually, after Clinton’s reelection, he was confirmed. It took Garland some time to settle into the ruminative life of a judge. One of his first clerks, Clare Huntington, recalls that he would often come back from lunch and ask, “Okay, who called?”

“And it was like, ‘Nobody,’ ” she says.

Garland built a moderate voting record and a reputation for working across ideological divides. He had a fastidious approach to writing opinions that would culminate with his reading the text aloud to his clerks from a standing desk, making corrections with a yellow pencil. “He would literally go over every word and every punctuation mark,” recalls his former clerk Karen Dunn, now a prominent Washington attorney who remains close to Garland.

When John Roberts was a judge on the appeals court, he and Garland implemented a process called “de-snarking.” The liberal and the conservative read over each other’s opinions to make sure neither said anything too heated. “The idea is that these sort of clever negative cuts toward judges on the other side are both unnecessary and unhelpful,” Garland told his former law clerk Maggie Goodlander (who served as counsel to the first Trump impeachment inquiry and is now one of Garland’s advisers at the DOJ) at a public talk last year. “Judges are human beings, and they don’t like to be attacked in that sort of snarky way either, however thick-skinned you think we are.”

To hear his friends tell it, Garland’s un-snarky attitude extends even to the Republicans who not only blocked his 2016 nomination to the Supreme Court but denied him the dignity of a hearing. “We went back and forth on that,” says the Harvard professor Laurence Tribe, who is friendly with Garland, one of his former students. “He basically said, ‘Don’t worry about me.’ ” If Garland had complaints, he kept them to himself, just as he had in 1996. “I think he handled it with extreme grace,” Dunn says. “I think he genuinely did not take it personally.”

Garland is, in many ways, not a man of this time. Biden reportedly considered a range of candidates for AG — including Doug Jones, who was coming off three tumultuous years in the Senate, and Sally Yates, a #resistance hero — but it was Garland who best fit his favored Cabinet profile: moderate, mild-mannered, and well known to old Democratic hands. Biden intended to return Washington to seriousness, and who would be more judicious than a judge?

But nine long weeks would elapse between Garland’s selection and the day he took office. In the interim, the investigation began barreling along an aggressive track — guided by a prosecutor with a conspicuously different approach to the rule of law and the uses of the media spotlight. On January 6, dressed in running clothes, Michael Sherwin was mingling with the police who were watching Trump’s “Save America” crowd. A bald and blunt-spoken former Naval intelligence officer, Sherwin was a career federal prosecutor from Miami — a hard-ass schooled in that office’s knock-down-the-door-and-seize-the-Ferrari culture. He had risen fast in Trump’s Justice Department by handling sensitive investigations into a Chinese trespasser at Mar-a-Lago and a mass shooting by a Saudi Air Force pilot. Now he was the acting U.S. Attorney for the District of Columbia — an outpost roiled by political interference in the cases against Trump acolytes Roger Stone and Michael Flynn.

After Trump’s speech, Sherwin followed the marchers as they confronted police officers guarding the Capitol and began to scale the scaffolding erected for Biden’s inaugural. He alerted the FBI, which was scrambling to coordinate a response, and later joined law-enforcement officials as they regrouped at a nearby command post. As a result of Trump’s dissension-stirring at Main Justice, the acting attorney general and other top officials were apparently hesitant to act. “Rosen, as far as I could tell, was hiding under his desk,” says a Justice Department official who served during the Trump administration. (Rosen did not respond to requests for comment.) Sherwin took control of the initial stages of the criminal investigation.

In the immediate aftermath, federal officials were reported to be focusing on the organizing role of Trump’s loyalists, including leaders of the “Stop the Steal” movement such as Stone and Alex Jones. Sherwin said he was willing to pursue “all actors, not only the people who went into the building” — potentially even Trump himself. Within days of January 6, Sherwin had created what he called a “strike force” of prosecutors specializing in national security and public-corruption issues, declaring that “their only marching orders” were to build serious conspiracy cases against leading participants in the attack.

More than 350 defendants had been charged and more than a thousand subpoenas and search warrants had been issued by the time Garland was sworn in. On March 11, his first day as attorney general, Sherwin went to brief him at Main Justice. Sherwin was ready to divide the cases he called the “one-offs” — which could be disposed of with quick guilty pleas to trespassing or other minor charges — from the defendants who appeared to have shown serious malicious intent. The latter group made up less than 10 percent of the total, he estimated.

The most politically charged decision for prosecutors involved the issue of sedition. The rarely invoked law against seditious conspiracy makes it a crime to attempt to “overthrow” or “oppose by force” the authority of the U.S. government and carries a sentence of up to 20 years in prison. Charging some of the January 6 figures with seditious conspiracy would send a strong signal. But it would also require the Department of Justice to accuse a defeated president’s supporters of plotting an insurrection.

“I do think this is completely unprecedented and is going to be probably the most difficult part of dealing with the January 6 fallout,” says Gil Childers, a former federal prosecutor who flew out to Oklahoma City with Garland in 1995. “Do you make that decision to prosecute where you think you can get a conviction, but boy, is this really just going to further sour the political discourse in the country and even open the rift larger?”

Sherwin was already on his way out the door, preparing to leave his post in Washington and return to Florida. Before he left, he gave an interview for an admiring profile on 60 Minutes. “I wanted to ensure, and our office wanted to ensure, that there was shock and awe,” Sherwin said, describing the nationwide roundup of suspects. He indicated that “the evidence is trending toward” charging some with seditious conspiracy, adding that “I believe the facts do support those charges.”

The interview, which was not authorized by Sherwin’s superiors, caused an uproar at Main Justice. The department’s new leadership came down hard, asking an internal investigator to determine whether Sherwin had violated protocol by speaking about the ongoing case to the press without permission. Garland does not like prosecutors who look for attention on TV, and he doesn’t aim to inspire shock and awe. “He is the last guy who will feel it is incumbent to bring charges that might fail just because some idiot prosecutor said so on television,” says Larry Mackey, a former member of the Oklahoma City prosecution team. (Sherwin, who is now in private practice, declined to comment.)

Since Sherwin’s contentious departure, the volume of the January 6 investigation has lowered to a murmur. No one has been charged with seditious conspiracy, which is fine with some opponents of right-wing extremism. “This is to me just the kind of case where Merrick Garland will bring some real sober thinking,” says Mark Potok, a senior fellow at the Centre for Analysis of the Radical Right. “Sedition has a nasty history. It’s often used against people who are not in favor in society.” Members of the Oath Keepers, Proud Boys, and Three Percenters have been charged with a narrower (but still serious) felony, conspiring to obstruct an official proceeding, along with civil disorder and assault. But the possibility that those who incited the incursion might be held accountable for its violence has all but vanished as the Republican Party has rallied around Trump as its leader in exile.

In contrast to his immediate predecessor, William Barr, who enjoyed playing the culture warrior and slugging it out in public with Trump’s opponents, Garland has turned inward, focusing on steadying the battered department. Whenever possible, he has avoided confrontation and has made a number of decisions confounding expectations that he would decisively repudiate Trump. Most controversially, the department has continued to back Trump’s broad claim of immunity from a defamation suit brought by E. Jean Carroll, who, writing in this magazine in 2019, accused him of rape. This position could be logically extended to protect him from civil liability for inciting a mob. A former federal prosecutor recently wrote a Slate column headlined “Why Is Merrick Garland Defending Donald Trump?”

When it emerged that Trump’s DOJ had pursued leak cases that poked into the personal communications of reporters, members of Congress, their staff, and even their children — some of which carried over into the Biden administration — Garland briskly announced an internal investigation and held a peace summit with officials of top news organizations. (Naturally, the meeting was off the record.) Influential voices, including the publisher of the Washington Post, have called for a systematic review of the DOJ’s actions during the Trump administration. Garland has so far resisted the idea. The Post’s Jennifer Rubin recently labeled him “the wrong man for the job” in an excoriating column. “Afraid of being accused of partisanship,” she wrote, “he chooses not to do his job.”

Many who were expecting a grand legal Ragnarok with the Trump era have been bitterly disappointed. (The latest legal danger for the former president, the indictment of the Trump Organization on July 1, has come from New York prosecutors.) Under Garland, the January 6 prosecution has remained narrowly focused on those who actually breached the building — leaving untouched, for now, those who encouraged or organized the attack from afar. This may be the right course to follow from a legal perspective. But the event is now being treated as a deranged riot, not as an attempt to usurp the peaceful transfer of power or as an act of domestic terrorism, as Biden described it in the heat of the moment. Only the rabble who crossed the Capitol threshold are being held accountable.

On Memorial Day, I met with Albert Watkins, an attorney representing several of the defendants. He had flown to Washington on a private jet to take a guided tour of the Capitol to help him to prepare to defend his clients. “I too found repugnant what I saw on TV on January 6,” he said. “My heart, my mind, at that time was Who the fuck are these morons?” Watkins said he has since come to believe that his clients are just suggestible dupes who were intoxicated by Trump.

Watkins’s most notable client, the “QAnon shaman” Jacob Chansley, had appeared tattooed and shirtless, in a horned fur cap, on the dais of the Senate and left a note for Mike Pence: “IT’S ONLY A MATTER OF TIME JUSTICE IS COMING!” “I think they fucked up by moving as quickly as they did up front, treating these people as insurrectionists,” he said of the Justice Department prosecutors. “I have a client who, for better or worse, he won the best costume contest of the day.”

Watkins, thin and jug-eared, seemed to be enjoying the attention the case is receiving. As he sipped a beer at a Georgetown bar, he flipped through some iPhone photos he had taken at the Capitol. “It’s hard to defend somebody,” he said, “when there’s roughly 287 million miles of video footage of your client being where he’s not supposed to be.” He also represents Felicia and Cory Konold, siblings from Arizona charged with criminal conspiracy. Prosecutors have presented photographs of the Konolds marching with Proud Boys dressed in tactical gear along with a monologue Felicia posted to Snapchat in which she says, in part, “We fucking did it.” Watkins is challenging whether his clients understood reality well enough to have criminal intent.

A few days before, Watkins had told Talking Points Memo: “A lot of these defendants — and I’m going to use this colloquial term, perhaps disrespectfully — but they’re all fucking short-bus people. These are people with brain damage. They’re fucking retarded. They’re on the goddamn spectrum.” The quote had been widely condemned, but the lawyer didn’t care. Watkins may be a blowhard — his own website describes him as “self-centered, egotistical, and a self-proclaimed expert in all matters” — but he is representative of a freak-show political culture that Garland cannot wish away.

It’s an asymmetrical battle: Garland offers abstract commitments to impartial justice and the rule of law, and Republicans bash in the rhetorical windows. At a House committee hearing in May, a GOP congressman from Georgia likened the mob invasion to a “normal tourist visit,” while another from Arizona demanded to know, “Who executed Ashli Babbitt?” Republican members of the Senate Judiciary Committee, including Ted Cruz, have questioned what they call the “stark contrast” between the January 6 prosecutions and the department’s handling of crimes related to last summer’s Black Lives Matter protests. “This is highly alarming,” Senator Ron Johnson recently said on Fox News. “Every American should be concerned when we see the unequal administration of justice.”

Already, the conservative media is full of dire warnings of socialist repression — a grotesquely distorted reflection of the resistance rhetoric of the Trump era. When Garland announced his new strategy to combat domestic terrorism in June, Tucker Carlson delivered a paranoid monologue on Fox News. “So because of January 6, says the chief law-enforcement officer in the United States of America,” Carlson said, “we must now use law enforcement and military force to arrest, imprison, and otherwise crush anyone who leads opposition to Joe Biden’s government … We are living through the transformation of a formerly democratic republic into something else. We are looking at growing authoritarianism.”

Some of Garland’s admirers worry that he has been too wary of public confrontation. The day before the Senate voted on Garland’s nomination, Tribe expressed the hope of many liberals, telling me that as disappointed as he had been to see his former student denied the Supreme Court seat, he was now happy to see him poised to play an even more “historically significant role.” More recently, Tribe, who continues to talk to Garland, said that the attorney general had come to a crossroads. “I think if he continues to disappoint in a way that many people think he has thus far and does not appear to see the bigger picture,” Tribe said, “that will be terribly significant but profoundly dismaying. But if he does what I think he is capable of doing, he will have moved the country in a dramatic way past the terrible cliff that would have spelled the end of the democratic experiment.”

In recent weeks, the Department of Justice has started clearing what Garland might term the clutter, offering deals to some of the lesser trespassers and selfie-snappers. The first defendant to be sentenced, an Indiana hair-salon owner, pleaded to a single misdemeanor and was given probation, community service, and a $500 fine. A Tampa man who entered the Senate chamber carrying a Trump flag recently pleaded to a single felony. His sentencing — recommended to be in the range of 15 to 21 months — may set a standard. A hearing will be held in July. “Everyone else is sitting back and eating popcorn,” says the man’s lawyer, Patrick Leduc.

The more complex conspiracy cases against the Oath Keepers, Proud Boys, and Three Percenters are likely to move at the justice system’s normal, deliberate pace. Two members of the Oath Keepers have pleaded guilty to conspiracy and agreed to cooperate with prosecutors. Still, the conspiracy cases are not slam dunks. “Did they all get together and say, ‘We are going to break into the building’?” asks Mackey, Garland’s former prosecutor in Oklahoma City. “How do I find the crime in this mountain of evidence? Anything beyond individual trespass, you’re going to have to show that there was an agreement among the people to violate the law. You start digging and you may or may not find a conspiracy.”

Even if those cases end in convictions, though, it is not likely to satisfy those who hoped the Trump era would end with a courtroom thunderclap. “That’s not the role of the criminal-justice system,” says Aitan Goelman, a Washington attorney who was also a prosecutor on the Oklahoma City case. “You’re not going to get some awesome closure.” The DOJ’s job — at least when the system is functioning properly — is to win convictions, not to provide resolutions to political conflicts. Garland is leaving the partisan crisis to others and concentrating on Justice, narrowly defined. Then again, from a distance, prosecutorial discretion can look a lot like passivity.

More on Insurrection Day and Its Aftermath

- Insurrectionists in Purgatory

- The Making of a MAGA Martyr

- The End of the End of American Exceptionalism