A couple of months ago, I set out to embark on a West Coast road trip of epic proportions; from L.A. to Portland, I would traverse the country’s most scenic highways and forests, allowing Waze to freely navigate me as I prayed my 1979 Mercedes Diesel didn’t fail me. My boyfriend suggested we help quell the inevitable boredom of hours in the old AUX-cord absent car by recording our own voices on the GPS app, rather than listening to some subservient British AI woman named Jane. I wasn’t aware this was an option, nor was I amused by it. Not only do I hate listening to the sound of my own voice, but I am utterly repulsed by the prospect of having to talk to myself for hours at a time.

The Waze feature that allows users to set their voice directions with their own recordings is an interesting one. It’s a new feature, from their latest update, most likely a simple idea to jazz up long commutes and road trips, and maybe induce a laugh akin to the one I had when I tried out Waze’s much-imitated “boy band” setting — which sounds more like a haunted doll than Harry Styles. But Waze’s decision to feature a record your own voice setting might have deeper implications for the politics of voice-command technology — and for our own self-consciousness.

When I hear the sound of my own voice on a recording, I am convinced I sound like a ditz, my high-pitched tone precluding me from professional success or the ability to be taken seriously by anyone listening to me. (This becomes especially challenging when I must transcribe one of my interviews, cringing at my vocal fry and chronic uptalk.) I have succumbed to the fact that my self-confidence and my conception of my own voice are incompatible; in order to maintain the former, I have to forget that the latter exists in a space outside myself.

I’m not alone. Studies dating back to the 1960s have shown that many people express discomfort at the sound of their own voices, often so surprised by the way it sounds that they fail to recognize it. The phenomenon can be traced to the fact that when we speak, we’re essentially hearing ourselves in surround sound, with the vibration of the vocal cords and their transmission via the skull making our voices seem deeper than they actually are.

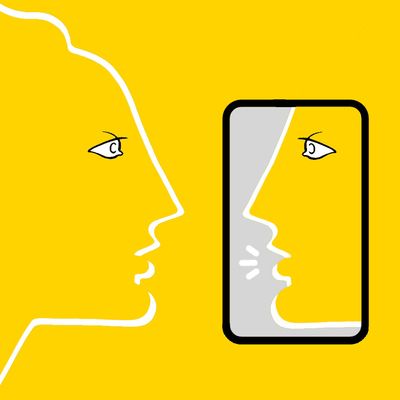

The cringe associated with hearing one’s own voice can be thought of as “a shock of self-consciousness,” as the Cut’s Melissa Dahl writes. So when we hear our own voice in recording, we are forced to confront a Lacanian sense of self, eroding the boundary that comfortably separates the experience of the “lived body” and the “corporeal body.”

That uncanny valley of semi-existence extends to the general concept of voice-assistant technology. In their ability to both predict and react to our everyday needs, voice assistants are, fundamentally, extensions of ourselves. But when most voice assistants are feminized — Siri, Cortana, Alexa, even Bank of America’s new AI — they produce an othering effect, normalizing female subservience. While women undeniably bear the brunt of the issue, it ultimately stems from the human tendency to command and control others. Everyone wants to be a boss, but what happens when we mechanize that desire in our most private spheres? (Studies showing the increasingly rude behavior of children offer one bleak picture.) Even as companies move to provide alternative settings to the stereotypical fembot AI, prompted by efforts like the Arianna Huffington–backed Equal AI Initiative, a problematic power dynamic remains for voice assistant technology. A chorus of moral tech panic has arisen, demanding a disruption.

Could self-imposed voice technology be a sort of solution?

My version of Waze demanded that rather than rely on an external agent of artificial intelligence — and yell at him or her when it inevitably delivers the directions too late, or tells me to get off the highway onto a long and winding road to avoid three minutes of traffic — I do something I’m utterly terrified to do: talk, and listen, to myself. The experience was at once frightening and alluring; it was like looking in the mirror, coming to terms with both my subjectivity and my self-presentation. “Turn left.” Okay, Sarah. Ew, I better not actually sound like this. I think it’s my speaker or Bluetooth or something. “In a quarter-mile, turn right.” Why aren’t I telling myself the street names? How am I supposed to know? Okay, calm down, Sarah. Actually, your voice sounds … better here? Maybe? “Police reported ahead.” Thank you, Sarah, for saving me from a speeding ticket. You always have my back! Remember that one time you got a speeding ticket because you were bored and challenging yourself to go faster while listening to your country-music playlist that you reserve for interstate highway travel? God, that was so dumb. That’s what you get for listening to Luke Bryan unironically. You got what you deserved. Oh shit, focus on the road! Stop listening to the sound of your own voice echo back in your head in all its high-pitched dullness or you’ll trail off this street like the end of your sentences.

Each car trip became a journey of acceptance, sure, but also a reckoning with what it means to be eternally at war with the body, with what cannot be looked at or listened to too closely, lest it become jarringly unfamiliar. Subtracting the lens of our own biases, breaking down that barrier between the corporeal and the lived experience, we reduce ourselves to the kinds of anonymous monads we brush by on the street — judging from a cool distance, before remembering how little we really know about this swift passerby.

With its ever-present power dynamic, a consistently smooth paradigm of dominance and submission, smart technology voice assistants pose an existential threat to human self-perception. In a world where we are consciously othering inanimate objects, an opportunity to break open that bubble of consciousness, in all its ugly recognition, remains a vital exercise. After all, smart technology can exist without voice commands. Every time we open Gmail, it learns more accurate responses to customize at the bottom of our emails, working seamlessly with inbox minus the antagonism of “Alexa, turn on the lights,” or “Siri, call Mom. I said, SIRI, CALL MOM!”

If a voice assistant helps us make daily decisions, from determining which highway exit to take to initiating impromptu dance parties, does it really make sense to treat it as a mechanized butler with a cold voice and a colder heart? The voice assistant is already an extension of ourselves; perhaps it only makes sense that it also echo our voices. When we give robots personality, we feed into the dangerous psychological tendency to offload our responsibilities — and anger, frustration, greed — onto another being. “There is no doubt in my mind that we will have a human–robot society, with robots embedded in every aspect of our lives,” said Matthias Scheutz, a professor of human-computer interaction at Tufts University. “That means we have to think about what we want that future to look like. What does it mean for you have a robot at home and treat it as a social other, even though it was not intended for that?”

In all its innocuousness, Waze’s voice settings may present a road map for the future of voice assistance: one that challenges us to become the Other ourselves.