- REVIEW

- READER REVIEWS

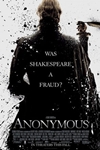

Anonymous

|

(No longer in theaters)

|

|

Genre

Drama

Distributor

Sony Pictures

Release Date

Oct 28, 2011

Release Notes

Limited

Official Website

Review

Roland Emmerich’s Anonymous is a well-polished cowpat that will confuse and bore those who know nothing about Shakespeare and incense those who know almost anything. It does have the trappings and suits of scholarship. Derek Jacobi starts the movie off in modern Manhattan, striding onto a Broadway stage and declaiming in tones more forceful than those I heard from him last spring at BAM (where his Lear ran the gamut from petulant to dotty) that Shakespeare left not a single manuscript behind, and that the true story of the author of Hamlet is much darker. He is Edward de Vere, seventeenth Earl of Oxford, who could not, by virtue of his rank, have anything to do with the theater and so handed over his masterworks—many of which were not performed until well after his death—to a boobish actor named Will Shakespeare, who incidentally was the one who stabbed Christopher Marlowe in the eye. Less improbably, De Vere screwed Queen Elizabeth, as well as (accidentally) his own mum.

The script by John Orloff skips back and forth between the aged De Vere (Rhys Ifans) and his younger self (Jamie Campbell Bower), although the actors neither look nor sound like each other and transitions are nonexistent. (The old and young Elizabeth I have an easier time, being played by the mother-daughter tag-team of Vanessa Redgrave and Joely Richardson.) Ifans is forced into unbecoming poses such as freezing in horror when his puritanical wife discovers him with pen and parchment (“You’re … writing again!”), but it’s always fun to see him affect a grave countenance. I was puzzled, though, by his placid demeanor during the first performance of Hamlet, in which the killing of Polonius comes before “To be or not to be”—but I suppose Emmerich would regard that as an academic quibble. He’s lucky he’s 400 years beyond the scope of Britain’s laws of libel and sedition, or else Shakespeare, Marlowe, Ben Jonson, the Cecils père and fils, as well as Elizabeth I would be giving him a royal escort to the Tower.

Apart from its ineptitude, Anonymous is peculiarly beside the point. Shakespeare’s succession of masterpieces, near masterpieces, and thrilling misses is a miracle no matter who did the actual writing: the actor-manager from Stratford-upon-Avon with the grammar-school education or De Vere, Francis Bacon, the Earl of Derby, or Marlowe after faking his own death. Although the least implausible, the Oxfordian case—initially predicated on the idea that no one so meagerly schooled, untraveled, and unacquainted with court life could possibly have written so discerningly about kings, queens, thanes, and Danes—is so unbuttressed as to be laughable, whereas books like Stephen Greenblatt’s Will in the World make splendid sense of the Stratford Shakespeare’s religion, politics, and sympathetic imagination. Moreover, Shakespeare spent enough time on and behind the stage to know what plays and what lays—something well beyond the ken of Orloff and Emmerich.

Related Stories

New York Magazine Reviews

- David Edelstein's Full Review (10/31/11)