- REVIEW

- READER REVIEWS

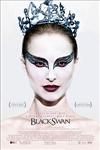

Black Swan

|

|

Genre

Drama, Suspense/Thriller

Producer

Mike Medavoy, Arnold W. Messer, Brian Oliver, Scott Franklin

Distributor

Fox Searchlight

Release Date

Dec 3, 2010

Release Notes

Limited

Official Website

Review

In The Wrestler, Darren Aronofsky crafted a battering ode to male masochism, to the notion that one is truly, ecstatically alive on the brink of self-obliteration. And now, for the perfect insanity-inducing double bill, comes that film’s female counterpart, Black Swan.

The protagonist is Nina, a New York ballerina played (and largely danced) by Natalie Portman. She is still, in essence, a girl: sexually immature, living with an infantilizing mother (Barbara Hershey), surrounded in her pink bedroom by stuffed animals. She’s also a serial puker who scratches herself until she bleeds, a spirit in limbo. Nina is a candidate to play the Swan Queen in Tchaikovsky’s Swan Lake, but her company’s artistic director (Vincent Cassel) maintains she’s suited only for half the double role. She is the very embodiment of the innocent White Swan, who kills herself for love. But for the dark, demonic twin, Nina is sadly lacking in life experience. Like a Method-acting guru, he lectures her on letting go, losing herself, surrendering completely to her sexuality.

Black Swan dramatizes that surrender and its overpowering side effects, and it plays like a Roman Polanski remake of Showgirls—with dollops of other Gothic/Grand Guignol filmmakers: David Lynch (life’s a dream), David Cronenberg (life’s a dream that makes icky things sprout from your flesh), Brian De Palma (life’s a voyeuristic tracking shot), and even that Italian giallo maestro Dario Argento (life’s a dark mirror that will shatter and slash you). The camera follows about a foot behind Nina’s slender neck as the settings change and doppelgängers pop up left and right. The movie’s epitaph could be “Double, double toil and trouble.”

Although Nina tells the director that her goal is “perfection,” she doesn’t really mean artistic perfection. In The Company, Robert Altman moved back and forth between physical (and emotional) punishment and sublime ballets, but Aronofsky isn’t remotely interested in celebrating the Dance. Black Swan is full of scary-looking emaciated women, their dark hair severely pulled back, twisting and cracking their limbs and toes—puppets of a tyrannical male deity. Even before Nina begins to unravel, the dances are shot by a camera that seems to be shuddering in horror.

Aronofsky has one overriding aim: to get past the blood-brain barrier and give you a drug experience. In his first feature, Pi, an obsession with a mathematical equation caused a stroke, while pills and smack dictated the fractured syntax of Requiem for a Dream. In The Fountain, he even made love a lethal intoxicant. Aronofsky is enough of a virtuoso to bring that aesthetic off, but it’s a painfully constricted vision, and, like most drug experiences, it leaves little behind but a hangover. At their worst, his films suggest that there’s a thin line between the hypnotic and the stupefying.

Portman gives the kind of performance that wins awards, largely because you’re so aware of her sacrifices to play the part. She looks as if she trained hard, and, for an actress, she dances well—although not brilliantly or distinctively enough to convince you that the company director would single her out. Toward the end of Black Swan, her face is all bone and hollows, like a shrunken head; it comes as a relief to gaze (too briefly) on the full, rounded features of Mila Kunis as Nina’s insinuating, fake-solicitous rival. Meanwhile, Hershey’s tight face emblemizes another, more Hollywood brand of female insecurity and masochism. Aronofsky cast Winona Ryder as the aging prima ballerina whom Nina replaces, and I couldn’t help but think he was exploiting her reputation as an increasingly unstable ingenue who crashed and burned. The movie is full of casualties—they could all win awards.

Black Swan is crushingly obvious from its first frame to its exultant final whiteout, with poor Cassel having to utter variations of the same exhortation in every scene. (When he directs Nina to go home and touch herself, Aronofsky makes sure we see the giant stuffed bunny near her bed.) But this is, no doubt about it, a tour de force, a work that fully lives up to its director’s ambitions. It takes a long time to purge Tchaikovsky from your head: You exit, pursued by a swan.