- REVIEW

- READER REVIEWS

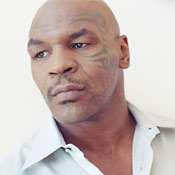

Tyson

|

|

Genre

Documentary

Producer

Damon Bingham, Harlan Werner, Michael Tyson

Distributor

Sony Pictures Classics

Release Date

Apr 24, 2009

Release Notes

Limited

Official Website

Review

No filmmaker i know has gotten as close to a professional athlete as James Toback gets to Mike Tyson in his new documentary. Early in Tyson, Toback uses split screens to show different parts of his subject’s face, and the effect struck me as too flash until I grasped the connection between those boxes and the urgency of Tyson’s mission: to rearrange the pieces of his life, bring order to his turmoil—tell his story. Tyson is all Tyson, an 88-minute stream-of-consciousness monologue that has you by turns sympathetic, perplexed, appalled, and enthralled. Even when Toback cuts to interviews from 25 years ago, there’s no loss in fluidity: The pieces are joined. The film is a pipeline into Tyson’s inner world—a dangerous place that all at once makes sense.

At the heart of Tyson is a contradiction: Its subject, who grew up in a fractured home in a violent neighborhood, trusted no one, confided nothing, and learned to channel childhood humiliation into “outsmarting and out-timing” people—into what he calls the “art of skulduggery.” Yet here he is in close-up pouring out what he thinks and feels and thought and felt in a high, gentle, lisping voice. It’s as if he’d been waiting for Toback to come along—Toback the effusive, brilliant, pickup-slash-bullshit artist who cultivates in himself the Maileresque White Negro, who revels in public humiliation as if convinced it makes you stronger.

In 1999, Toback invited the disgraced boxer to play himself in a party scene in the polarized and polarizing Black and White, then directed Robert Downey Jr., as a gay producer, to sidle up and proposition the champ—who went after Downey for real. Toback, who loves controlled chaos, rejoiced at this improvisation, and Tyson—who always had a touch of the drama queen—must have had an inkling that one day he’d be able to bare his soul in the care of this primal therapist. Can this really be Tyson—the man who nearly bit off a boxer’s ear, twice—describing himself as a shy weakling adolescent scared of bullies, putting all his emotions into raising pigeons? The punch line of the story (literally) is when a neighborhood thug wrings the neck of a beloved bird and Tyson scores his first-ever knockdown. After that, everyone must have seemed a potential pigeon-murderer. Juvenile detention liberated him. It introduced him to boxing, as well as to Cus D’Amato, the surrogate father with the rambling upstate house who taught him to be a “spiritual warrior,” and whose death would set the stage for Tyson’s infinite emotional regression. Footage of his fights in those days evokes primal terror: You’ve never seen such hard punches thrown so fast. Tyson’s narration knocks the wind out of you, too. It’s driving and incantatory; it puts you inside his head as he performs the sacred ritual of breaking in his gloves and then locks eyes with his opponent. (“They make a mistake when they look down for a tenth of a second …”) You hardly believe what you’re hearing: “I aim at the back of my opponent’s head … fantasize going through the head … Every punch is thrown with bad intention.”

Women are his Achilles’ heel: Great men, Tyson avers, conquer famous women and realize too late “how much they take from you.” The issue remains a source of confusion to the champ, who longs for a strong woman, perhaps a CEO, to take care of and protect him and also let him dominate her sexually. Of the legendary interview in which his then-wife, Robin Givens, told Barbara Walters that her life as a newlywed was “pure hell,” Tyson wonders how he could have sat there in silence, thereby implying assent. He was “a pig,” he admits, but adds: “We were just two kids. The whole world was in our business … Just kids … Just kids.” As for his rape conviction, Tyson continues to plead not guilty—and given his confessions in Tyson of other bad behavior, I believe he believes that. I also believe he’s too damaged to feel much empathy. Perhaps he’s so brilliant at bringing us into his head because he hasn’t yet learned to see himself through anyone else’s eyes.

Toback’s Tyson has a different energy than the fighter we see in flashback. His face, even adorned with Maori warrior tattoos, is wide open. There is no hint of the man once caught on camera yelling at a heckler, “I’ll fuck you in the ass, you faggoty white boy … I’ll fuck you till you love me, faggot.” This Tyson is the one seen telling a TV interviewer after losing his final fight that he only did it for the money and he’s sorry to have let people down: “I don’t have that ferocity. I’m not an animal anymore.” What he is at the end of Tyson is unformed, a father looking forward to being a grandfather. Toback’s camera holds on him, as if asking, “What is a man who defined himself by acting out when he sheds the role of his life?” He is back to thinking about pigeons, waiting for the release of this movie and a new kind of celebrity.