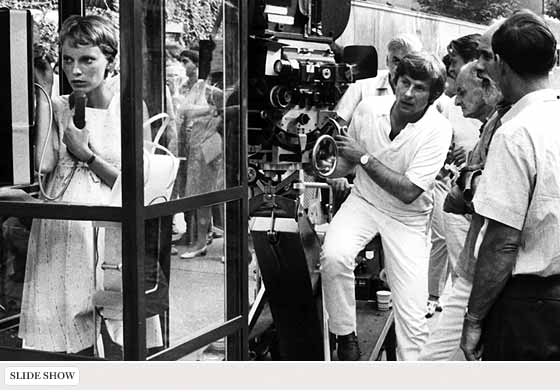

Our streets are thick with cinematic ghosts. Just consider the Dakota. It practically glows with the afterimages of Lauren Bacall, Judy Garland, John Lennon, and Boris Karloff—residents all—alongside the lingering spirits of Rosemary’s Baby. In fact, Mia Farrow’s demon child was born in 1966, the same year as the Mayor’s Office of Film, Theatre & Broadcasting, which is now celebrating its 40th anniversary with the book Scenes From the City: Filmmaking in New York. Rosemary’s little boy prefigured the apocalypse, but the Mayor’s Office helped stave one off—or at least it seemed that way to New York filmmakers, who were noticing a few too many movies shot in squeaky-clean city streets built on Los Angeles back lots (see Rear Window). Instead, the Mayor’s Office simplified a hydra-headed permit process and ushered in a heyday of New York cinema that prided itself on the kind of grit you can’t fake. Last year, New York’s television, film, and advertising industry broke records with 31,570 shooting days, having snapped back from a brief downturn in the wake of the tech bust (and then 9/11). Commissioner Katherine Oliver says that “business is booming” since a 2005 tax break made studios even more willing to work here. Hollywood may be panicking over its business prospects these days, but New York film hasn’t felt this robust in years. Just look at the current new-releases list: Shortbus, A Guide to Recognizing Your Saints, Fur, Infamous, Man Push Cart, Little Children, even Borat. And the auteurs keep coming: Sidney Lumet just wrapped a film with Philip Seymour Hoffman—and Wong Kar-Wai just shot part of his English-language debut, My Blueberry Nights, in a Chinatown bakery. How sweet is that?