In the indie universe, Miranda July is a polarizing force. To her near-fanatical followers, she is the undisputed high priestess of the DIY art revolution—a bold, multitalented 33-year-old sprite with a refreshing, almost childlike sincerity who seems to have sprung fully formed from the evergreen forests of Portland, Oregon. They point to the sprawling, highly intelligent body of work she has created over the past decade, ranging from performance art to music to installations at the Whitney Biennial to a Sleater-Kinney video to her 2005 Caméra d’Or–winning art-house hit Me and You and Everyone We Know. They adore what they see as her uncanny ability to mine universal truths from surreal details and illustrate what it’s like to be human and lonely (and a little bit weird) in a post-human era.

But to her detractors (many of whom are just the sort of Cookie Monster– T-shirt-wearing indie-film buffs you’d think would love her), the mere mention of her name sets off groans. For them, she serves up preciousness in place of thoughtfulness, trafficking in the worst faux-earnest indulgences of the post-McSweeney’s brigade.

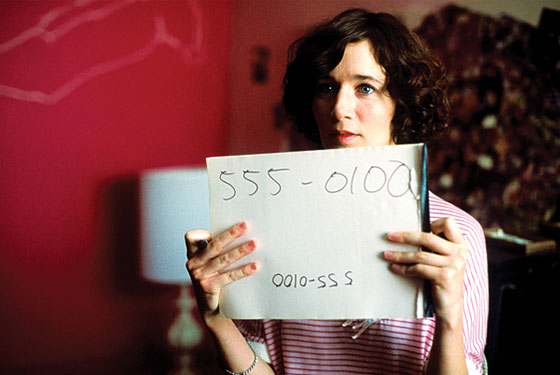

A lot of the trouble seems to stem from Me and You and Everyone We Know, for which July was writer, director, and star. Told in a deadpan Todd Solondz manner, the film follows Christine (July), an oddball video artist in pursuit of Richard (John Hawkes), a reluctantly divorcing shoe salesman with two young sons. The movie was funny (a grown woman unknowingly has a cybersex chat with a poop-obsessed 7-year-old) and sweet (a 7-year-old unknowingly …), its social observations often dead-on. But like Napoleon Dynamite and other love-the-loser films, it also swerved once too often into quirkier-than-thou smugness—freak chic. The sight of July’s character calling out “I love you!” to a goldfish that was about to fall to its death was enough to make one wish Hemingway would step into the frame with a shotgun.

“I’m not saying it worked,” admits July when I ask her about the goldfish scene over breakfast in Chelsea. Dressed in a fifties robin’s-egg-blue skirt-and-sweater set with bright-red tights and a fake flower pinned in her hair, July is pretty in a carefully cultivated, slightly gawky way. “When I look back at it, it definitely feels like the movie of my twenties, which were all about longing,” she explains. “I was trying to get at different kinds of love and show the ways that they all sustain us. You know, you think you want just romantic love, but what’s actually keeping us going is all these different kinds of love.” July’s latest exploration of love is her debut collection of stories, No One Belongs Here More Than You, the publication of which raised the obvious question: Would the book settle the “Miranda July, Awesome or Annoying?” debate for good?

Once again, we are in the land of lonely West Coast weirdos—in one story, a broke young woman gives swimming lessons on her kitchen floor to a bunch of senior citizens; in another, a man in his sixties who works in a purse factory becomes obsessed with a teenage girl he’s never seen. “The stories aren’t technically autobiographical, but in an emotional sense, they are,” says July, who long kept her ambition to write a secret. Both of her parents are writers in Berkeley, and July (whose given name is Miranda Grossinger) grew up amid the nonstop chattering of Selectric typewriters and towering cardboard boxes full of the alternative books her parents publish through their mom-and-pop company, North Atlantic Books. (Titles include Chi and Creativity, The Anti-Estrogenic Diet, and Supercharging Quantum Touch.) Much of her childhood was spent listening to the rants of “borderline crazy writers,” along with disturbing seventies-style confessions from both parents about their personal and marital challenges. “I wasn’t neglected at all, but my parents didn’t have the best boundaries in the world,” says July, who dropped out of college at 20 and fled to Oregon. “I was privy to pretty much everything about their lives.” She pauses. “I think that’s definitely where my desire to be the one who understands comes from.”

In Portland, July fell in with musicians like Sleater-Kinney, and she recorded two albums on the influential Kill Rock Stars label, featuring experimental audio work along with tracks from a brief, platinum-haired “rock star” stint with the band the Need. And it wasn’t until 2001 that July—at the urging of Rick Moody—got around to trying her hand at fiction in earnest. “Rick came to see one of my performances. He told me that he’s secretly a performer—he’s in a rock band. I said, ‘Well, I’m secretly a writer,’ so he offered to read some of my stories.” Moody gave his stamp of approval, along with suggestions like, “It would be good if something happens outside the narrator’s head.” And soon enough July’s odd, strangely erotic fiction was appearing in The Paris Review.

She didn’t think about putting a book together, though, until 2005. Worn out from the press tour for Me and You and Everyone We Know, July (who now lives in Los Angeles with her boyfriend, director Mike Mills) found herself blocked: “I felt so self-conscious from that year of talking about myself so much. It really screwed me creatively.” She returned to some stories she’d written years earlier, fretting over their quality. But “it suddenly occurred to me that of all the things I could do, finishing this book was probably the best use of my time,” says July. “Everything I wrote seemed terrible,” she recalls, but she made herself continue.

It’s a good thing she did. If the territory in No One Belongs Here More Than You seems familiar, her treatment of it is different, less coolly twee (one influence seems to be Denis Johnson, another chronicler of American loserdom who could hardly be accused of fetishizing quirk). There is a marked new maturity at work in these stories—a determination not just to chronicle her characters’ obsessions and idiosyncrasies, but also to understand the purpose they serve. July is still interested in longing, but it’s the dark, inarticulate heart of longing she’s after now. “What happens when you get rid of all of longing’s disguises?” she asks. “Is it really that you want the thing so badly, or do you just enjoy wanting it?”

Has the debate been settled? (Are indie taste debates ever settled?) No, but this round goes to July.