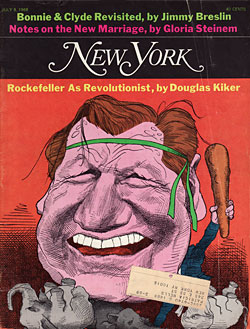

From the July 8, 1968 issue of New York Magazine.

I did not like it the first time I saw it. The movie Bonnie and Clyde was the biggest thing in the country when my friend Fat Thomas and I went to see it some months ago. We went early on a Saturday night, at six o’clock, so the place would be empty and we could put our feet up and smoke cigars, but we still didn’t like the thing.

Right at the start, Warren Beatty, who plays Clyde Barrow, was standing on the streetcorner and he pulled out a pistol and showed it to Faye Dunaway, who plays Bonnie Parker. She began to run her hand on the black barrel of the pistol. Run her hand on it lovingly.

“That’s a lot more than a pistol right now,” I said.

“She gets one of them jammed into her back, she don’t go around petting it, I guarantee her that,” Fat Thomas said.

We began to discuss which was sicker, the airedale dog they put into a love scene in Here We Go Round the Mulberry Bush or the broad gently petting the gun in Bonnie and Clyde. When Fat Thomas and I saw the airedale dog in Mulberry Bush, we were in a private screening room and both of us began yelling out, “Look out for the hoof and mouth disease.” The people who put either of these scenes, the gun or the dog, on the screen should have their hands held over the kitchen stove, but if you have to choose between the two, it is no contest. The thing with the girl petting the gun is a much sicker proposition.

After the gun scene, the movie progressed in similar fashion. The photography was striking. The light usages ran from haze to flat to crystal-like and it was wonderful to watch. But there always was this studied, playing-with-yourself handling of guns. Now when we were kids, the big movie, the biggest maybe, was Kiss Tomorrow Goodbye with Jimmy Cagney. The great scene in the movie, the one we all clapped for, came when Cagney had a rat stool pigeon locked in the trunk of his car and the stool pigeon’s muffled voice said he wanted air and Cagney grinned and said, well, we’ll give you air, you rat stool pigeon, and he took out a gun that was bigger than he was and put six shots into the trunk. It was Cagney’s face and style of body movement which captured everybody. You never noticed the gun. Cagney played a tough guy so intensely that he was comical. But here in Bonnie and Clyde, it was different. The gunfire was more important than the faces, and everything was cloaked in beauty. At the end of the movie there was this very pretty machine-gunning of the two stars. Pretty people in pretty sunlight and neat holes in them and a pretty white dress billowing and Clyde rolling around in clean, pretty grass.

Both of us sitting in the movie had the same reaction. “What the hell do they call this?” we said out loud.

Well, of course, we walked out of the movie and into a splash of Bonnie and Clyde promotion. The picture was doing knockout business, the reviews were out of sight, there was a song about it on every juke box, the department stores were featuring Bonnie and Clyde fashions and at a cocktail party with all smart people, somebody brought up the picture and everybody said, oh, was that great, and I murmured something about why I didn’t like it and a real smart woman turned on me.

“You didn’t really see it,” she told me. “The idea was to provide a revulsion at violence. That was what the over-kill at the end was for. It signified revulsion at violence, don’t you understand?”

Of course, I went back on myself. I don’t go to many movies and I figured I wasn’t up with what they are doing on the screen, so I was showing some basic strain of illiteracy by not liking the movie. I looked down at my drink and said, well, I guess you’re right, and I let the thing go at that. I did the same thing the guy from Newsweek, Joe Morgenstern, did. He wrote a review knocking the movie and he heard so much criticism of the review that he went back and did another one, and the second time he said the picture was great.

In all the months that the picture was around big, I only heard of one person who was against the picture so much that he wouldn’t even go and see it.

He was riding in a car in December in Chicago, going to the Book and Author Luncheon at the Chicago Sun-Times and the car went past a theatre playing the movie and Bobby Kennedy said, “What about that movie?”

“I hear it’s terrific,” somebody in the car said.

“Best picture of the year,” somebody said.

Kennedy stared at Chuck Daly, one of the people in the car.

“I hear it’s the most immoral movie ever made,” Bobby Kennedy said quietly.

Everybody let it pass without a discussion. The little guy always was especially interested when it came to guns.

Since then, two lifetimes that I know of have passed. And a lot of others that I just read about it in the papers, or on sheets of statistics. So the other day, on a hot, muggy afternoon, a Sunday, we were in the station wagon driving the kids to the beach, to Rockaway Beach, so they could surf, and we were coming along Woodhaven Boulevard and we stopped for a red light right across the street from a movie theatre I used to go to when I was a kid. The name of it is the Cross Bay, and it was right under the El in Ozone Park, a couple of blocks down from the clubhouse entrance to Aqueduct Race Track. And the marquee of the Cross Bay said, Bonnie and Clyde and underneath it, The Endless Summer.

“Out of sight,” one of the kids said.

“What?” I said.

“The Endless Summer. We saw it four times,” he said.

“I think I want to see the other one again,” I said.

“… It was Cagney’s face and style you noticed, not the gun …”

I said I would see everybody later, and I got out of the car and trotted through the traffic and went up to the movie. The usher at the door said there was a half hour of The Endless Summer left, and then Bonnie and Clyde would come right on. I went down the block to a candy store and bought a yellow legal pad and a couple of black Bic pens. I was going to watch this movie closely. I was going to watch it closely because in Los Angeles, early in the morning, we had all been drinking coffee out of containers on the sidewalk in front of the Good Samaritan Hospital and somebody, I don’t remember who it was, said, “We’re living in a country that makes Bonnie and Clyde the best picture of the year.” Then everybody made these quiet, bitter remarks about that and the thing stuck with me, and the minute I saw the sign on the marquee of the Cross Bay Theatre, I decided to go in there by myself and sit quietly and look at this thing real close. Maybe it would tell me something. So I paid $1.75 and went into the Cross Bay and watched the end of The Endless Summer and waited for my movie to come on.

Of course, I was bringing problems into the place with me. To begin with, there was this narrow balcony in front of the cluttered second-floor motel room in Memphis. There was a chicken bone on the balcony and part of the cement, the part which caught Martin Luther King’s blood, had been scrubbed. Andy Young sat on the bed in the room and talked in this terribly wounded voice about the single rifle shot which had come earlier in the night. Then, two mornings later, on the plane to the funeral in Atlanta, Roy Jenkins, who was the British Home Secretary and now is Chancellor of the Exchequer, sat by the window and said, “Delighted to meet you,” and then he began talking about violence.

“We’ve had two assassinations in England in recent times,” he said. “General Sir Henry Wilson was shot outside his house in Eaton Square. That was in 1921. Of course, it had to do with the Irish problem and you could place your finger on the reason. It was really an act of war, you might say. The last actual assassination in Great Britain was Spencer Percival, the Prime Minister. He was stabbed in Parliament.”

“When was that?” Jenkins was asked.

“Oh, the beginning of the 19th century. I think it was 1817. Yes, I think you’ll find that’s the correct year.”

Later that day, in the heat of the Ebenezer Baptist Church, Charley Evers, whose brother Medgar had been assassinated, broke down and sat in tears in a pew running along one wall of the church, and Bobby Kennedy, who had had a brother named Jack, came and sat next to him and grabbed Charley Evers’ arm very hard. Outside, walking in the hot street, Kennedy said, to himself as much as anybody else, “Here’s Evers, and somebody introduced me to a girl in church and said it was Malcom X’s sister, and, gee, you begin to think every family has to have somebody killed over this thing.”

Later, on the way to the Atlanta Journal newspaper office, the streets were vacant and there was no place to get even a glass of water. On one street, two blocks away from the newspaper office, a sign over a store said “Sporting Guns,” and I walked down to it, expecting it to be the only shop open in all of Atlanta. It wasn’t open, but it wasn’t a very good gun shop, either. There were only a couple of big .45’s on cardboard display signs in the windows. The rest of the store seemed bare. But they are a terrific piece of goods, these .45’s. You can go out today and go for your lungs buying a new Cadillac and in three years you have a piece of junk. There is no built-in obsolescence in a .45. The model was made in 1895 and hasn’t changed and you can leave one of these guns in the family for 150 years and it’ll still be good enough to blow the brains out of somebody in the family tree.

King was buried in May. In June, on Tuesday morning, June 4, 1968, the rush hour in Los Angeles was moving through a dull, muggy day which was keeping the smog close to the ground. Bert Prelutsky of West magazine drove us along a freeway, against the traffic, out to Orange County, an area that has a million people, Disneyland, the Anaheim Stadium, Knotts Berry Farm and, in Garden Grove, the headquarters for George Wallace. At Fullerton, the highway was alive with the sound of Southern California. Motorcycles racing while waiting for the light to change. In the background, plastic flags strung around auto lots flapped loudly in the exhaust fumes blowing against them. The highway was lined with take-out food shops, soft-water laundries, dry-cleaning stores and stainless-steel-and-saran-wrap supermarkets. A one-story red cinderblock building sat in the middle of this jumble. The sign painted on it said “Warner’s Gun Shop.”

A red-haired woman sat at a desk behind the counter that took up half the store. The other half was filled with gun racks. The woman was drinking coffee and smoking a cigarette. She said her name was Nita Bomgaars and she was from Arkansas, originally. “My husband, he was eventually from Iowa,” she said.

“My husband comes here after work and he spends time here weekends,” she said. “He keeps his regular job. He’s a millwright. That’s like a machinist. We just built this place two years ago. When you open a small business, you can’t expect to make right away.”

“Is a gun shop a good small business’” she was asked.

“Oh, it could be a very good one here, some day. You know, he can quit the regular job and we can just run this business here. It could be a good business right now, except we can’t get what we want.”

“What do you want?” she was asked.

“Smith and Wessons. We just can’t get them. Had so many people in here ordering .45 Highway Patrolman model and we could only get two of them. Nine millimeter shells. I couldn’t get them either.”

“Why the shortage of Smith and Wessons?”

“You see, they’re doing so much government work and after that police work, that any time they have left over for retail production, it goes to old customers. When you’re just starting like we are, you can’t get them.”

The glass showcases under the counter were filled with Berettas. There was a Ruger Single Six. “Only one of them I have,” she pointed out.

The literature on top of the counter consisted of Shooter’s Bible. 1968 Edition, a book as thick as a Sears Roebuck catalogue: World’s Guns and DuPont Presents The Handloaders Guide to Powders.

We walked around the back of the store, where rifles stood upright in racks, the wood gleaming the same way baseball bats do in a sporting goods store. She had enough rifles to outfit a line company.

As we were leaving, the woman said, “Yes, Smith and Wessons, that’s what you need to make it in this business today. We just can’t get them. Get a lot of off-brands. I’d like to carry used Smith and Wessons, but I can’t get them either. You know how it is, not many people are trading their guns in these days.”

Back in Los Angeles, at 11:30 at night, in suite 511 of the Ambassador Hotel, Bobby Kennedy sat on the floor against the wall under the windows and smoked a cigar. He was talking about coming into New York on Thursday or Friday and going on television to pick a fight with the New York Times. He had been burning for a shot like this for months. He said the Times was anti-Catholic and he was going to challenge them on it. “Their idea of a good story is. ‘More nuns leave convents than ever before’,” he said. Somebody said that a sure way to make page one of the Times was to present a story about a priest being caught in bed with a girl. Kennedy got up and walked over to his wife Ethel to repeat it. He came back and sat down and twirled the cigar and looked up when he saw activity by the door.

“Are we going down now?” he said.

“I think so,” Fred Dutton said. “We’ll wait just a minute and we’ll go.”

“Fine.”

He leaned back. “Where did you go today?” he said.

“Out to Orange County.”

He smiled. “That’s the place,” he said.

“It’s beautiful.” he was told. “I met a woman there who was starting out with a small business of her own. Her and the husband. He works because the business isn’t making enough just yet. You know what kind of small business they opened?”

“What kind?”

“A gun shop. How do you like it? A gun shop. This whole place out here is crazy.”

He made a face when he heard the word gun. It was the face he always made when somebody told him something that was so bad he didn’t want to hear it. The eyes shut tight, the lips parted and the teeth gritted. He made that face when somebody would tell him their son had just been killed in Vietnam. Or when some desperate amateur would talk to him about his brother’s death.

“… There weren’t many movies in India when they killed Gandhi …”

Fred Dutton nodded to him a few minutes later and Bobby Kennedy, holding the cigar, walked out of the room and went downstairs to the ballroom. After his speech, he was shot in the kitchen behind the ballroom. He was shot with long-nosed bullets from a .22 Iver Johnson eight-shot pistol. The pistol had a black barrel. The pistol originally had been bought in the summer of 1965 by a 72-year-old man who lived far from Watts, but was afraid that the Negroes were going to run through the streets and come and get him and his family. The pistol had been passed along over the years until it came into the hand of the killer standing in the kitchen. It was one of 2.5 million handarms registered in the State of California, and if there are 2.5 million registered, then there must be another 3 million unregistered. So on any given day in California, you could raise 5,500,000 people for a gunfight. Just with handguns. Rifles and shotguns? They’re like knives and forks in a house.

So now, after a few months of standing on the side and watching all these other things, I sit in the Cross Bay movie house and The Endless Summer dissolves and, right away, these family snapshots come on, with the sound of a camera shutter clicking each time a new one appears. It is the start of Bonnie and Clyde. I take the pen out and lean in the aisle so the light from the candy counter shines on the yellow legal pad. I begin to watch the picture.

What I think is the trouble shows up right away. The girl is lovely. The guy is good looking. I mean, if you’re a woman, he must be a helluva looking guy.

But out in the streets it never works out this way. Take the girl. Well, the only girls I ever knew who carried guns and stepped out on heists were bull daggers. I knew a broad from Ridgewood named JoAnne and she rode motorcycles and she went on a payroll heist and when the judge gave her two-and-a-half to five in the women’s prison at Bedford Hills, she said she wanted to whisper “Thanks.”

Now look at the man. He’s playing a killer and he’s handsome. This doesn’t go. I mean, what the hell is this all about? You want to see a real killer, then you should have been around to see Lee Harvey Oswald. He was a miserable looking son of a bitch with blackheads on the sides of his nose and dirty sweat showing on the top of his chest, where he had the collar of his plaid sports shirt opened. The Dallas police brought him out of an office into a jammed hallway so they could take him to the bathroom and everybody got a good look at him. Richard Speck fits here too. He killed eight nurses in Chicago. He had slimy hair and acne all over his face. He stayed in flophouses that had no baths and he put cologne over his sweatdirt-streaked body so nobody would smell him. James Earl Ray is a guy with a prison face. Sirhan Sirhan has grainy skin and greasy hair. When they got him up on the metal table in the kitchen, his eyes were bugged out and rolling around. When somebody got at him and gave him a good choke, his tongue flopped out of his mouth and the teeth around it looked rotten.

Now the Mafia has some good-looking killers. But the Mafia is different. They do straight political executions. When they shoot somebody, the people who knew the victim throw a block party. They don’t bother you. The thing that cuts into your sleep is an acne-faced creep coming out of the woodwork and pulling the trigger at somebody who is good. On the plane coming back from the funeral in Washington, John Seigenthaler, who was in the Justice Department when a Kennedy ran it, kept shaking his head and saying, “All the people we went after, major criminals, and in the end the ones we should have been worried about were little sick creatures running around waiting to shoot a President.”

Anyway, here is a motion picture starting. It has pretty people who kill, and the killing they do is pretty too. When Warren Beatty shoots a man from a bank who is hanging on the running board of the car, he shoots through the rolled down window and the bullet makes the’ glass spider web in a great pattern and the red splurts in a nice splotch of color between the banker’s eyes, where the bullet is supposed to have gone. The scene probably was supposed to chill you, but it was really quite pretty. The patterns and light refractions and color all were excellent and pleasant. In a real murder, there is a grease-slicked, pebbly gray cement floor with dirty water slopping around and the smell of sour ovens and the heavy smell of sweat from people crowding around the body and then through it all, the smell of blood.

I was making notes on the dialogue, which was, like most movie dialogue, truly magnificent.

HER: What’s it like?

HIM: Prison?

HER: No, armed robbery.

HIM: Slow grin with good white capped teeth showing.

Armed robbery is not a grin. It really isn’t. Armed robbery is this old woman on Pitkin Avenue in Brownsville, Brooklyn, on the floor behind the counter of her husband’s tailor shop clawing at the three bare-armed cops from the emergency squad who are trying to stuff her 72-year-old husband into a body bag. He is dead from three bullets in the head over a $10 stickup. One of the bullets went through his eyeglasses and the bits of glass are everywhere on the floor and the old woman is on her hands and knees and she comes off her hands to claw at the three cops and then she falls onto her hands again and screams.

In another part of this movie, the guy is teaching the girl to shoot a gun and she throws one off and jumps with joy and blows the smoke from the black barrel of the gun. He starts saying something about, “I’m goin’ to get you a Smith and Wesson …”

I begin thinking about a face now. A magnificent dark brown face coming through the glass doors and into the hallway of the Hospital for Joint Diseases in Manhattan. Leary, the police commissioner, and Garelik, the chief inspector, and Bluth, another inspector, have been standing in the hallway waiting to see the face. Pollins’ wife. Pollins is a narcotics detective and he is upstairs dying because a junk peddler caught him in the face with a shotgun. The three bosses of policemen are waiting in the hallway to tell Pollins’ wife exactly where everything stands. They keep saying it is a very hard thing to do, but they have been through it before and they can handle it. They can tell a young woman that she is going to be a widow with children. “Guns,” one of them said. “Dirty Mother—guns.” Now this great face comes into the tile hospital hallway and the three of them, Leary, Garelik and Bluth, turn as one and start walking away, walking very fast, because they have to get a priest to tell this woman. There is no such thing as a man being tough enough to handle this job. And I go into a phone booth because I don’t want her to see my face, either. I remember her face, though. God, but she was a stately woman.

So when you had all these things going through your mind and you sat in this movie and started to put it all together, you had to be careful because it is so easy to say the movies breed the violence. All the treatises going around now about violence in America all mention Bonnie and Clyde. Here, right on the desk by the typewriter, is a caption from Life. “The casual acceptance of violence, epitomized in the movie Bonnie and Clyde (right, Bonnie is gunned down), creates a climate which some scientists believe can arouse susceptible people to violent acts.” Maybe. But they had no movie houses to speak of in India when they murdered Ghandi and Bonnie and Clyde had not been produced when a Japanese jumped up and assassinated a leader right in the Diet. The movie can arouse, perhaps. But it is only a reflection, a beautifully done reflection, of what really arouses the people who murder in this country.

Well, to me, what the picture really stands for, is the thing noticed most the first time I saw the movie. The girl petting the gun. You see, the movie is all about playing with things. Playing with yourself, really. And it is in tune with the times, Bonnie and Clyde is. We are not a violent society. This is actually a society of jerks and for some of them the gun has got everything to do with it. Lee Oswald couldn’t make it with his wife and I bet he got his kicks when he shot Jack Kennedy, and James Earl Ray ran around Toronto buying pornographic pictures, and the way Sirhan Sirhan hung onto that freaking gun of his when great big guys tried to get it off him—Bill Barry and Rosie Grier and Rafer Johnson had him and he still wouldn’t let go of the gun—the way this little guy with the rotten face hung onto that gun, don’t tell me what he was doing, he was hanging onto himself. They are, all of these shooters, the ultimate products of an era of masturbation, of Playboy Clubs and Andy Warhol movies and Truman Capote parties. And they are from the new bit with the cops out West, leather puttees and black leather jackets and big, creaking gun belts and fancy-handled guns and crash helmets and sunglasses, all worn in a certain way. In Memphis, when they were putting Martin Luther King’s casket onto the plane, the cops stood in a line and they all were dressed like Nazis, with a good dose of sadism represented in the black leather. One guy, a moon-faced captain, stood there with his crash helmet strap hanging loose and a cigarette dangling from his mouth and he held a submachine gun so nice, and he kept running his hands over it so much, that all of us standing by the fence made it 7-5 that the gun was going to have an orgasm.

There have been 800,000 murders by gun since 1900 in this country. There have been 42,000 murders by gun in the period between 22 November 1963 and the early morning of 5 June 1968. The murders took place in a country which has guns everywhere. A federal gun law enacted now will not have any other immediate effect except to make shooting somebody maybe a little less respectable. You see, in the South you still get a clap on the back if you get your kicks by shooting a buck nigger. The gun law will make a real difference maybe 15 years from now. The only effective thing which can be done at the present is to outlaw the sale of bullets. We have the guns everywhere. Cut down on bullets and you might have something.

It still won’t do anything about the conditions and the atmosphere in which people use guns. All these murders took place in a country which has virtually nothing on television that does not come down to gunplay, and this is because it is really all the people watching television want to see. And the movie that created the biggest splash in the entertainment field is Bonnie and Clyde, which is all about pretty people playing with guns, and the public loved it.

When the last scene came on the screen at the Cross Bay, the pretty machine gunning, and the picture ended, I got up and walked outside into the late Sunday afternoon sun. I stood in the shade under the rusted El and waited for a taxi. I had just seen what is, in the end, a fine movie. Bonnie and Clyde caught a piece of this country as it is today, and this is all you can ask of any movie.