Slumdog Millionaire is a low-budget R-rated movie shot entirely in India with no stars, filmed partially in Hindi, and based on the TV show Who Wants to Be a Millionaire. It’s also a transcendent love story that has swept up festival awards and critics’ raves on its way to becoming a legitimate Academy Award contender for Best Picture. If Slumdog, opening November 12, pulls off one of the greatest upsets in Oscar history, it will be because:

A. It’s the ultimate Danny Boyle film.

B. New Mumbai is the old New York.

C. It’s the Obama to Dark Knight’s McCain.

D. It is written.

Consider your final answer:

A. It’s the ultimate Danny Boyle film.

When Manchester, England’s Boyle broke out in 1996 with his hallucinatory Trainspotting, it wasn’t just a bug-eyed mockery of Glaswegian heroin addicts. It was a scorching rejection of conservative Thatcherite Brits who wasted their lives watching “mind-numbing, spirit-crushing game shows.” Mostly though, it was cinematic smack for a new generation of counterculture film junkies.

Boyle is now a 52-year-old father of three, and he’s still searching for the next cinematic rush. Given his stylistic preference for hysterical realism and his noted distaste for game shows, the idea of making a film about what even Slumdog’s screenwriter, The Full Monty’s Simon Beaufoy, merrily admits is “the most spirit-crushing game show of all” left Boyle cold. “When my agent said, ‘It’s a script about Who Wants to Be a Millionaire,’ I almost didn’t read it,” he says, all spiky hair and excitable gestures, rocking back and forth in a posh Gordon Ramsay restaurant. “The only reason I did was because it had Simon’s name on it. Then fifteen pages into it, I had no doubt.”

The first fifteen pages, loosely based on the novel Q&A by Vikas Swarup, start at a gallop and break into a sprint: A call-center tea servant named Jamal (Dev Patel, of the BBC’s Skins), raised in the horrific slums of Mumbai (a.k.a. Bombay), has made it to the final round of India’s Who Wants to Be a Millionaire. But before he can answer his final question, he is escorted from the building, arrested, and tortured by the police—because no “slumdog” (as slum kids are referred to in India) could possibly know the answers.

The game show is just a device—a familiar frame for Westerners (the film’s mostly in English, but essentially a foreign feature). The real tale begins during Jamal’s interrogation, when he explains how he knew the answers—triggering a breakneck series of flashbacks that take him from age 7 to 13 to 18. It’s a neo-Dickensian race through a brutally violent and corrupt modern Mumbai. But difficult as it gets for the characters, the film doesn’t “moralize about India or try to reform it,” says Boyle. “You just get thrown in the deep end.”

Fans of Trainspotting will remember a particularly vivid scene involving a toilet. And it was a toilet again that nailed Boyle’s interest in the Slumdog script.

Scrappy young Jamal gets locked in an outhouse as everyone in his slum runs to greet a visiting Bollywood star. The only way out? Jumping into the fetid hole beneath him. Jamal, the unstoppable dreamer, plows through the crowd covered in excrement, and scores the only autograph. “Oh, God, what a scene!” Boyle raves. “He’s got this dream—and all this shit to get through. That’s Jamal, right there.”

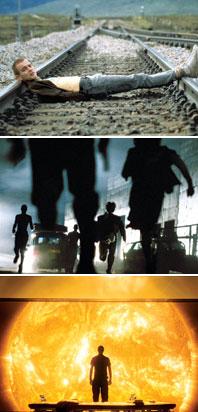

It’s nearly impossible to draw a through-line from one Boyle film to the next, because his films are so diverse. But watching Slumdog, you see flashes of everything he’s done before: the technical madness of Trainspotting, the gleeful romance of A Life Less Ordinary, the fast-paced, digital-video grit of his zombie flick 28 Days Later, his warm touch with amateur kid actors, explored in his underrated drama Millions—even the grand gestures that defined his two big-budget misses: the Leo DiCaprio soul-searcher The Beach and his sci-fi movie Sunshine.

“The degree of difficulty—it’s an amazing achievement,” says Fox Searchlight President Peter Rice, now pushing Slumdog in six-plus Oscar categories. “To go into the slums of Bombay and come out nine months later with this virtuoso movie. Like, ‘Where did that come from?’ ”

Boyle has never done well with big budgets: “A huge amount of money precludes risks,” he says. So after spending three years with Sunshine, he relished the absurd challenge of leading a skeleton crew into a place he knew nothing about.

Boyle says he’s always been “hooked on the kind of adrenaline you get in cities,” and has said that he’d love to make a film that’s “as mad and crazy and heartbreaking” as Apocalypse Now. In Mumbai, the filmmaker, as producer Christian Colson has said, “found a place that’s more Danny Boyle than he is.”

B. New Mumbai is the old New York.

With 13 million people living on top of one another, Mumbai is the biggest city in the world, home to the most prolific movie industry and some of world’s most dramatic contrasts.

“You imagine Scorsese in the seventies. You imagine what it must have felt like—that everything’s an opportunity,” raves Boyle, leaning into his argument, fingers flashing, as if animating the city in the air. “You go there, and it’s buzzing. The extremes you get are incredible! You cannot believe what you’re getting on film because you don’t go anywhere that’s boring. The city’s just exploding somehow. Destroying itself and re-creating itself at the same moment—the buzz you get off it!”

The buzz! Vibrated! Pulsed! Exploding! Destiny! Serendipity! Vivacity! Bang! Rhythm! Movement! Boyle didn’t storyboard this film, but if he had, you imagine it would look like something by Stan Lee—full of pows and bangs and blasts of color. To capture the insane energy and sordid beauty of Mumbai, Boyle and 28 Days Later cinematographer Anthony Dod Mantle skipped Bollywood’s elaborate studios and hit the streets: Using a prototype system, they packed hard drives in backpacks and used handheld lenses that made them look more like tourists than film crews. They shot 80 percent of the film in digital video—sneaking through crowds and into off-limits locales for some spectacular shots. They got kicked out of the red-light district, a gangster’s hideout, and the Taj Mahal.

“In Mumbai, the long routes take forever, so everyone takes the shortcuts through these dirty lanes and alleys,” says actress Freida Pinto, who plays Jamal’s love interest, Latika. “That’s exactly what the camera does, too, so you reach your destination so much faster.”

About midway through Slumdog, the soundtrack is thumping and the camera is whiplashing through the city’s streets, when suddenly a policeman shouts at the screen, “No filming!” Another director might have cut that moment, a ruined shot. Boyle left it in. “That’s what it was like!” he trills. “You leave it in the film because you can, because it breaks the wall. Because there are no walls anyway when you’re there. You can pretend there’s this fourth wall or pretense, but there isn’t.”

Likewise, the film combines unstaged street footage with pure gaga romance: “Realism is the foundation of everything I do,” he says. “If you’ve got that as a base, you can push as hard as you can so it stretches as much as possible.”

C. It’s the Obama to Dark Knight’s McCain.

At the Envelope, the Los Angeles Times’ Oscar blog, the lead contenders for Best Picture are currently David Fincher’s Benjamin Button (reported budget of $167 million), Christopher Nolan’s The Dark Knight ($185 million), and Slumdog Millionaire (just $13 million). It’s one of the most lopsided races in history.

But these days, anything seems possible. And the early favorite, Christopher Nolan’s box-office goliath Dark Knight, may soon seem dated, imagining as it does a fearful war-on-terror Gotham, in which an idealistic leader is crushed. With Oscar nominations announced two days after Obama’s inauguration, will such a dystopic vision be embraced? As Rice points out, cinema has always been the ultimate escapism during tough times, and Slumdog’s optimistic romance—coming as it does on the heels of desperate times—seem curiously timely. “In its underdog status and its message of hope in the face of difficulty,” says Searchlight COO Nancy Utley,” “the movie is Obama-like.”

D. It is written.

By nature, most directors are control-freak egomaniacs—but when Boyle arrived in India, he let go. “If you believe in serendipity, and they do in India, it’s the only way,” he says. “You can’t just go in with your normal approach. You’re not going to conquer it or control it.”

When professional kid actors seemed too polished, he cast kids straight from the slums: “As soon as we did, it was, like, bang! The door doesn’t just open, it smashes open.” He took copious notes from local casting director Loveleen Tandan, and as a result shot a quarter of the film in Hindi. “She said, ‘This couldn’t happen in English. It would happen in Hindi.’ I said, ‘Do you realize what you’re fucking saying? We’ve been given $13 million and … ’ Well, she was right. We made her co-director.”

Boyle turned the score over to Indian superstar A. R. Rahman, who says Boyle “just said he wanted a pulse—and no cellos!” Boyle even integrated script notes from pop star M.I.A., also on the soundtrack, and leaned heavily on assistant director Raj Acharya, who brought a very Indian approach to the production—call it controlled chaos. “Raj drove everybody mad, but I saw the film through his eyes,” Boyle recalls. “The crew would be screaming—he’d just fucking disappear—but I always sort of knew Raj was working the wave—what I call the wave, anyway. It was like surfing in Bombay: The waves would come and they would disappear.”

Watching Slumdog Millionaire is, in many ways, like surfing a big wave—terrifying and euphoric. It’s no spoiler to reveal that when the credits run, the kids join in a giddy Bollywood dance—a supremely cathartic, universal moment that makes Jamal’s difficult journey seem worth it. “We’re all a bit inhibited now—it’s so hard to feel,” Boyle explains, “but everyone loves to dance,” And, as we’ve learned, everyone also loves hope.