When the monologuist Spalding Gray was 18, his artistic life had yet to begin; in fact, his concerns at that age could be summed up by the title of the piece he’d later perform about his early manhood: “Booze, Cars, and College Girls.” From the boarding school to which he’d been dispatched by his disappointed parents, Gray and his friends launched a “lost weekend” that memorably ended with Gray abandoning a passed-out classmate on the street outside Boston’s North Station.

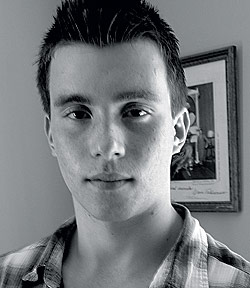

Two miles away and 51 years later, Spalding Gray’s son, now 18 himself, is sitting at a sidewalk table outside a coffee shop on a frigid fall evening. Forrest Gray’s Boston experience has been a little different from his father’s. “There are kids who are like, even on a Saturday—‘I’m going to go practice for four hours,’ ” he says about his fellow students at the Berklee College of Music. “Including me. It’s great to be in a place where everyone is just as serious about music.”

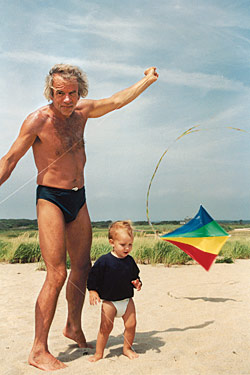

And Forrest is serious. He’s taking seven courses in his first semester at Berklee. And hand in hand with his father’s legacy, Forrest—who was just 11 when his father committed suicide by jumping off the Staten Island Ferry—has already launched his artistic career: His song “Sunset” is the touching coda to Steven Soderbergh’s new documentary about his father, And Everything Is Going Fine, which opens on December 10.

Forrest Gray blends in with the other Berklee students who fill this oddly music-centric block in Boston’s Back Bay. (Navigating the sidewalk is a challenge, given all the guitar cases and music stands.) His short hair, dark eyes, and prominent cheekbones make him a ringer for The Sorcerer’s Apprentice star Jay Baruchel. He doesn’t look much like his father, but he has his dad’s introspective streak. “I’m good at telling stories,” he says. “I’ve always been a good liar, even in middle school.” But he does not share Spalding’s compulsion for autobiography. “I just don’t like people knowing that much about me,” Forrest says with a laugh.

He describes his father as “like living with a teacher. He was teaching me existentialism, philosophy when I was, like, 4 years old.” Forrest, who has a younger brother, doesn’t remember much about Spalding’s 2004 disappearance. “He was distant years prior to that. So it was expected in a way.” He grimaces. “As bad as that sounds. But I had been prepping. It wasn’t like someone who goes out and gets hit by a car and, Oh my God, he died. It’s different.”

For Forrest’s mother, Kathie Russo, her son’s relationship with his father is intricately tied to his passion for the guitar. “He got interested the day they found Spalding’s body,” she says from the family’s house in Sag Harbor. “We’re waiting to hear confirmation from the police whether it’s him or not, and Forrest comes downstairs and goes, ‘Mom, I want a guitar.’ And I go, ‘Get in the car, let’s go.’ ” She says Forrest tucked the guitar into his bed that night—“as if it was a person.”

In 2006, Forrest’s rock group, Too Busy Being Bored, won the Knitting Factory’s battle of the bands. “Being the boasty, proud mother that I am,” says Russo, she sent press clipping to her friends, including Soderbergh, who had already begun work on his documentary. The director asked Forrest to submit songs for the movie, and chose “Sunset”—originally written for a project at the Ross School in East Hampton—to close the film. Kathie says that Soderbergh told an audience at an early screening that he’d been struggling to find an ending to the movie, and that Forrest’s song provided the close he’d been looking for.

Soderbergh’s movie begins, as all Gray’s monologues did, with the performer entering a room, sitting in a chair, and taking a careful sip of the water he always kept at hand. And Everything eschews the typical trappings of biographical documentaries—there are no titles explaining the timeline of Spalding Gray’s life, and the only talking head is Spalding’s. Nearly all of the film is made up of expertly edited excerpts from Gray’s own monologues and appearances.

That means that the movie doesn’t end, as many viewers might expect, with a note explaining the sad circumstances of Spalding’s death. Instead, Forrest’s song—elegiac and straightforward—plays over footage of Spalding as a child. Standing in as it does for tidings of Gray’s suicide, the song, already quite lovely, becomes almost unbearable.

“For me, it’s joyous and sad,” says Russo, who was involved throughout the five-year process of creating And Everything Is Going Fine. “And yet, at the same time, I feel so proud of Forrest that he was even able to do this.”

The next morning, Forrest is late for a 9 a.m. rehearsal with his jazz ensemble. “I slept through my alarm,” he mumbles, gripping a to-go cup of coffee. “I was up until 3:30 doing my Ear Training homework.” But once Forrest gets into the tiny rehearsal studio two floors underground, he perks up. The band, including his professor on alto sax, runs through a handful of standards, preparing for a concert a few weeks away. The bassist is AWOL, so Forrest deftly incorporates bass lines into his strumming. He sits with one sneakered shoe happily tapping out time atop the other, his short-sleeve shirt revealing the tattoo on his arm, a face taken from an album cover by the briefly popular Australian band the Vines.

The rehearsal finishes up with Wes Montgomery’s “Cariba.” The professor points to Forrest, indicating his turn to solo. Forrest is most confident and fluent on faster songs, and he has the jazzman’s knack for turning mistakes into happy accidents: A botched low note becomes the base for an energetic, atonal run. “Music saved my son,” Russo says, “from a horrible thing that happened to him.”

The song ends, and like his father in reverse, Forrest takes a careful sip of coffee, stands up from his chair, and exits the room.

And Everything Is Going Fine

Directed by Steven Soderbergh.

Washington Square Films. NR.