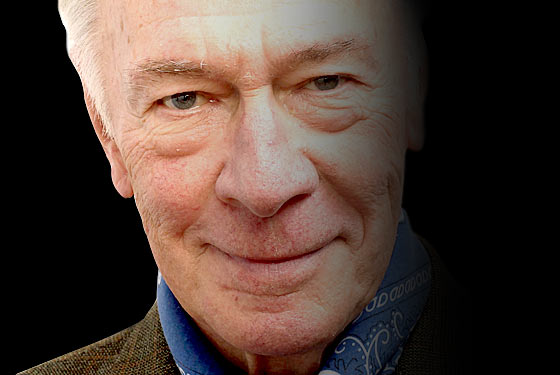

It’s hard to see why he isn’t Sir Christopher Plummer—actors of far less stature have been knighted—until you remember he isn’t a Brit but a Canadian, with an accent and attack that hover somewhere over the mid-Atlantic. Some of us have been lucky enough to see him onstage (his 1973 performance in the musical Cyrano was a high point of my theatergoing life), but he didn’t show his genius on film until 1999, as Mike Wallace in The Insider—a mischievously satirical performance, part payback, part celebration. Since then, there’s been little that hasn’t been superb, from his plangent vocal turns in animated films like Up and My Dog Tulip to his suddenly discombobulated Leo Tolstoy in The Last Station. At 81, he seems to have shed some years onscreen, losing that sinister, stick-up-the-butt aspect that was his trademark after playing Captain Von Trapp in The Sound of Music. (He has just completed a pivotal role in David Fincher’s The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo.) Living in Connecticut, married for four decades to his third wife, Elaine, who put an end to the exuberantly self-destructive lifestyle he writes about in his splendid autobiography, In Spite of Myself, Plummer is still peaking.

I spoke with Plummer in April, onstage at the Sarasota Film Festival, and last week after a Beginners screening. (The film is reviewed here.) There is no way to capture the range of the discussions or his dead-on imitations of everyone from Edward Everett Horton to—no kidding—Terrence Malick. But here are some highlights.

On playing gay in Beginners: “Goran Visnjic [as Plummer’s young lover] was nervous, ’cause he’s very butch, and he would be pacing up and down and saying, ‘My God, my God, we’ve really got to kiss,’ and I began to get petulant about it and said, ‘What’s so bad about kissing me?’ It was nerve-racking, but once it happened, it was rather pleasurable, actually … We fell into it as if we’d always been gay.”

On not milking his death scene: “My character, Hal, is happy to die knowing he has finally been honest with himself and known a great love. Same with Cyrano de Bergerac. I acted with José Ferrer, who was great in that role, but he made the mistake of crying at his own death, and I said, ‘That is something I can never do.’ ”

On why he wanted to be a bad-boy actor: “My great-grandfather was prime minister of Canada, and I had a very Edwardian upbringing. It was a beautiful, romantic way of growing up, until the family lost its money. And I decided to be bad and rough and find the streets rather than the gates. Most actors come from the streets, and their rise to fame is guided by a natural anger. It was harder to find that rage coming from a gentle background. I think anger does fuel a successful acting career. To play the great roles, you have to learn how to blaze.”

On his high-living early acting days: “Jason Robards and I used to play scenes on the stage, and after we’d say the line, we’d ask, under our breath, ‘Where are we starting out tonight?’ It was usually the White Horse Inn, and we couldn’t wait for the show to be over to invade that bigger show called life. I thought at one or two glamorous moments that I wasn’t going to last very long. I thought, If I make 35, it’ll be okay, and then at 40 I got scared, and now that I’m 81 I’m scared to death.”

On being a dark presence on the set of The Sound of Music: “There had to be someone involved who was a shit—cynical, naughty—and I think [director] Robert Wise was grateful for my presence because it helped him steer the movie from veering over the cliff into a sea of mawkishness. But I loved Julie Andrews. The littlest one, who played Gretl, was an absolute monster, she took such attention away from everybody else. Then years later, I was in a play on Broadway, and this blonde bombshell showed up in my dressing room and said, ‘You don’t remember me, do you? My name is … Gretl.’ ”

On reuniting with the cast on Oprah: “I was dreading it, but it was nice to see the kids again. Some have done very well. They didn’t all become actors. Wise …”

On a crucial piece of direction from John Huston on The Man Who Would Be King: “At the end, when they bring the head [of Sean Connery], [my character] Kipling looks at it and says some line, and I tried to cry, and finally John said, ‘Chris, just take the music out of your voice!’ And by Jesus, I suddenly learned if you have a terribly emotional line in a huge close-up, you just have to deadly whisper it. And if you look at those old movie stars—the John Waynes and Gary Coopers—when they have a deadly line to say, it’s absolutely straight. The face does all the rest.”

On playing Mike Wallace: “He was a wonderful villain. He recognized that television is there to humiliate us; it’s the medium of accident and spontaneity, and he used it brilliantly. He once interviewed me and said, with his usual charm and tact, ‘Tell me, Mr. Plummer, why you aren’t considered a household name.’ But I loved his sort of zeroing in and zapping you. I admired his guts.”

On romping with Helen Mirren in The Last Station: “We are old theater buddies, and when you’re making a Hollywood movie, that’s such a relief, to talk the same language. She, who will take her clothes off at the drop of the hat, is the most joyous person to know. We laughed our way through Tolstoy. Can you imagine?”

On acting for Terrence Malick in The New World: He’s fascinated by nature, and just cuts to birds. Colin Farrell kept saying, ‘My character, he’s a fuckin’ osprey. That’s how he sees me.’ You’d be playing a passionate scene, and he’d say in that strange southern voice of his, mixed with Harvard and Oxford, ‘Ah, jes’ stop a minute, Chris. I think there’s an osprey flying over there. Do you mind if I just take a few shots?’ I wrote him an infuriated letter because I saw the film and I was hardly in it—he cut my part to shit. And it recalled the story of Adrien Brody, the lead in The Thin Red Line. He went to the premiere, and he wasn’t in it! I wrote to Terry and said, ‘You need a writer, baby, you need somebody to follow the story.’ I was awful to him, but I did say I admired him. He’s an individual—also mad as a hatter.”