Minutes after meeting me at the Getty Villa in Malibu, John Cusack has concocted a plot for us to commit grand larceny. The Greek and Roman antiquities museum is closed to the public today, but open to us because one of us is John Cusack and we asked nicely. Its grounds are eerily devoid of people, its galleries minimally guarded. “That’s pretty wild,” says Cusack, grinning mischievously. “So, we could steal art.” But what to do about the museum’s willowy PR director, Desiree, who’s following us around to make sure we don’t touch anything? He suggests we cut her in, too. “We’ll all be tied to each other as felons for life. If one of us goes down, all three …”

Just as quickly as he dreamed it up, though, Cusack abandons the plan, having spotted something easier to pilfer: potato chips from the museum’s closed café. He couldn’t know they’re not free, but he doesn’t ask. He’s already digging in and offering me some before Desiree can tell him that, of course, he may help himself. He thanks her, grateful but not surprised.

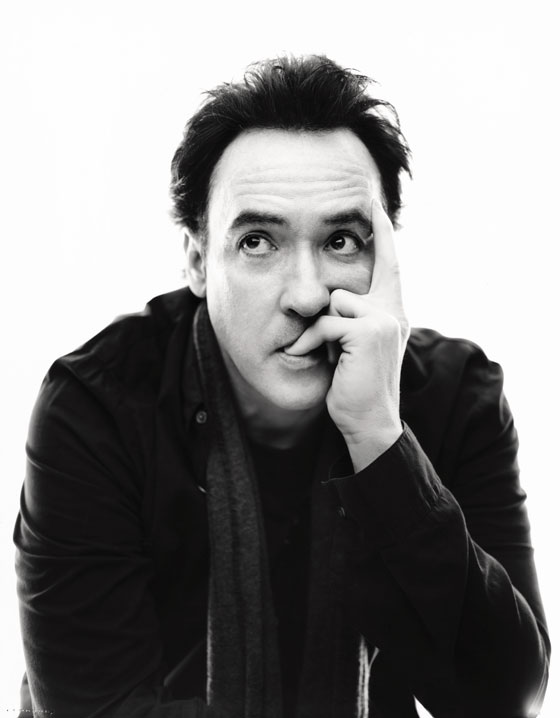

Cusack, now 45, has been making movies since 1983, which means he’s been famous for over half his life. Museums opening their doors just for him, or cafeteria food being his for the taking, are just normal things that he’s long since grown accustomed to—not out of a sense of entitlement but because why waste time feeling conflicted about good fortune? He’s reached a stage in his career, too, where his decisions seem to be driven mostly by whimsy and “opportunity”—a word that, along with “risk,” he mentions a lot. He took his latest role, as a washed-up, alcoholic Edgar Allan Poe in the thriller The Raven, from V for Vendetta director James McTeigue, because he felt like reading a lot of Poe. He’ll follow that with an experimental half-Spanish-language meta-comedy (working title: No Somos Animales), which he co-wrote, about an actor who moves to Argentina because he’s tired of making conventional movies. It sounds a little like a cry for help.

“I’m not trying to protect [a legacy],” says Cusack, who lives nearby in Malibu and keeps a home in Chicago, where he grew up, near his mother and actress sister Joan. Indeed, he gamely skewered his past in Hot Tub Time Machine, the 2010 sci-fi comedy in which four buddies travel back in time into what is essentially Cusack’s 1985 absurdist teen-skiing hit, Better Off Dead. “I thought, If I’m going to address my own career and be self-referential, at least I can be the one being mean to me,” he says. But when the studio pushed “to make things like American Pie and do puke and dick jokes,” he got protective. “They wanted me to do Say Anything jokes, but I thought some of it was a little lazy,” he says. “It didn’t earn that one.”

He pauses. “I guess people like Hot Tub Time Machine, don’t they? It’s culty. I do culty well.”

His culty-ness is why, he says, “I don’t listen to what people say [about my movies] right away, because later the people either like or hate them more.” Take The Raven. Under a period-piece surface, it’s a lurid murder mystery that finds Poe trapped in one of his own stories as he tracks a serial killer who’s using Poe’s stories as inspiration to bury people alive (“The Cask of Amontillado”) or gut them with a swinging blade (“The Pit and the Pendulum”). “This isn’t The King’s Speech,” Cusack says. “People challenging the conceit of the movie don’t know Poe that well. He wrote highbrow, esoteric poetry, but also lowbrow pulp for a Saturday-evening paper. He’d do cliffhangers. He’d have outrageous things like orangutans coming out with razor blades. It was horror.”

Cusack wants to check out the art. At home, he owns pieces from friend Ralph Steadman and spin paintings he made with Damien Hirst. He’d love to get some German Expressionists but can’t. “Not unless The Raven’s a really big hit,” he says, laughing. “The kind of art I love I can’t afford. You have to be in a different tax bracket than I am.”

The tax bracket he’s in can’t be too bad, though. When he’s not acting or tweeting prolifically about pop culture and politics (he’s liberal, but no fan of Obama these days), he says, “I go on adventures.” Those include snowboarding and driving a tripod motorcycle around South America. He still practices mixed martial arts, which he picked up while filming Say Anything, but doesn’t spar much anymore. “You can’t keep going to the chiropractor,” he says. In his off time on The Frozen Ground, a thriller he recently shot with Nicolas Cage in Alaska, he and friends would land a helicopter on an iceberg and smoke cigars, floating on the Arctic Sea. “That’s a pretty good day.”

We walk past an outdoor amphitheater where this fall, Desiree explains, the Getty will be staging Euripides’ Helen, in which the gods send Helen to Egypt for safekeeping while sending a ghost, or “Stepford Helen,” to Troy. Chaos ensues. Says Cusack, “I’d make that movie.”

He tells us his father once used Aristophanes’ The Birds as the basis for a play he wrote. “He sold his soul to advertising to pay for us, then did what he wanted to do, which was write. He passed away nine years ago.” Wandering through the galleries, Cusack admires a plump Aphrodite: “If she were around today, she’d get liposuction.” Of the museum’s prized artifact, a fourth-century bronze Greek athlete whose hand is raised to his ear, Cusack jokes, “He originally had a cell phone.” We pass a Dionysus. “Speaking of Bacchus,” he says, “that’s my man.” He touches the statues until Desiree catches him and asks him not to.

Cusack describes making The Raven as “like being on jag or a bender.” His Poe is so broke he’s reduced to shouting out poems in bars in hopes that someone will remember he was once great and buy him a drink. (I tell Cusack that sounds like a mid-career actor’s worst nightmare. He doesn’t bite.) On the three-month shoot in Serbia, Cusack says, he went a bit crazy. He didn’t sleep. He dropped 30 pounds. “I just got really, really thin. When I came back, I scared my family. They were like, ‘What have you been doing?’ ” But he liked being inside Poe’s head, temporarily. “There’s something romantic about toying with the abyss. But I wouldn’t want to stay there.”

The Raven was just the beginning of a dark, three-movie journey through the underworld for Cusack. He then shot The Frozen Ground, in which he stars as a serial killer (he based his portrayal of evil on crocodiles he’d seen on safari in Africa), and played a death-row inmate in Lee Daniels’s The Paperboy. To prepare for the three roles, he did Jungian shadow exercises, meditations designed to delve into parts of the subconscious you most want to hide. Did he discover a dark side he didn’t know about? “No, I’ve known about it forever,” he says, laughing. “But I’ve been tapping into it in interesting ways. If we don’t remember we’re fucked up and human, then the work isn’t compelling. That’s why, obviously, the job is not all about people who are evolved and happy, because there’s no drama there. We have to mine our secrets.”

Getting deep into character, he says, “felt appropriately binge-y. Poe binge-y.” But he stopped short of actually becoming a drunk: “I have enough experience with being a maniac that that’s close to the surface.” Drugs and alcohol, “that’s a younger man’s version of wild. If you live like Poe lived, you die.” So you go on adventures. You sit on icebergs, get skinny enough to scare your family, and sulk around Serbia doing Jungian shadow exercises. “It’s just changed form,” Cusack says. “You graduate to a higher level of maniac.”