Like so much of Will Ferrell’s work, the comedy Casa de Mi Padre is a prank without guile: It has a core of humanism that radiates out, past the layers of silliness, the tacky sets and bare-butt gags and absurdly splattery shoot-outs. The chief joke in this telenovela send-up is the mere notion of casting the blondish, middle-aged Caucasian galoot Ferrell as a simpleminded Mexican cowboy hero and having him speak entirely in Spanish—a language he didn’t know a few scant months before shooting. Unable to improvise as freely as usual, Ferrell chomps down on words like muchacho and lets the unfamiliar language slant his features in ways you’ve never seen. But he largely plays it straight, throwing the ball to his Mexican co-stars and looking, atop his majestic horse, nakedly earnest.

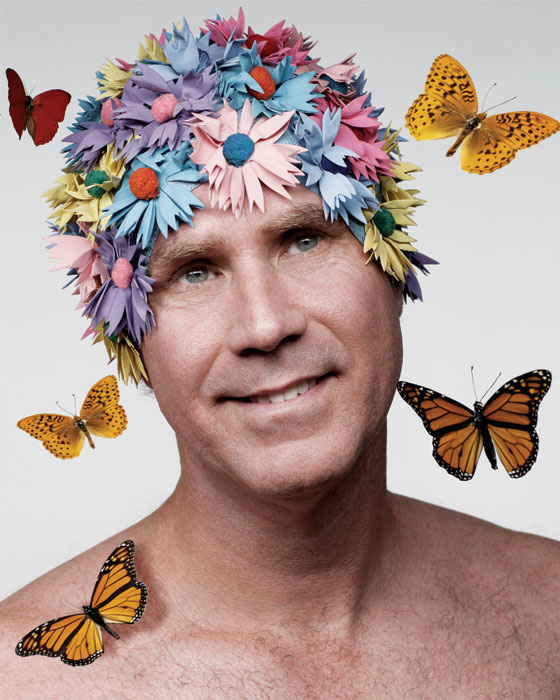

It’s the same expression he wears when I meet him at a West Village photography studio, the sun setting over the Hudson as he sits upright, trim in his tracksuit, sipping espresso and doing his best to answer pointy-headed questions about his unusual (for a great clown) mixture of the antic and the gentle.

At 44, Ferrell is the most centered exhibitionist in modern comedy—maybe too centered to have the slightest need to put himself on the therapist’s couch and muse on the psychological foundations of his comedy. Then again, the deadpan hides much. Growing up in Southern California in the late seventies with a single mom (although in regular contact with a dad who was an accomplished musician), he played sports, made crank calls, and gravitated to comics like Steve Martin. “Putting an arrow through his head and playing the banjo and always going for the non sequitur, that’s what I loved,” Ferrell says. “He obviously became gigantic, but I’m sure there was a big portion of that audience that was, like, ‘What is he doing? I don’t get it—it’s not a setup, punch line, or storytelling.’ ”

Ferrell actually strives to produce that disorientation. “I’ve never been afraid of silence,” he says. “Silence and listening in comedy are big things that are overlooked.” If you don’t get the joke, he can wait. Like a musician (it’s no accident his films are filled with musical numbers), he thrives on changing the beat and riffing on a theme, letting the gag go on “and on and on and on and start to dip, but then because it’s going on so long it starts to get funny again.”

The approach goes back to his long stint on Saturday Night Live, where he’d double down on sketches that were dying in front of the audience—unlike some of his plainly miserable co-stars. “If something wasn’t working, the tendency would be to speed up and get through it,” he says. “But I would slow way down, and I would have this thing—I don’t know why, I love the audience, I want them to laugh, and yet something would kick in like, ‘Okay, you don’t like it, I’m going to make sure you really hate it,’ so I would just take my time. I don’t know, it was like a perverse joy in the agony of it being so painful. I can’t explain that.”

Explaining what he does is a task that often eludes Ferrell, which is why, in the summer of 2010, he sent me an e-mail in a response to my review of The Other Guys, in which he starred with Mark Wahlberg. “This is a first for me, as I have never personally reached out to a reviewer, but I wanted to thank you for your kind words about our movie and myself,” he wrote. “I feel like for the first time a reviewer perfectly articulated what it is I do. It was so fun to read because I have a terrible time articulating it myself.”

Then he said he hoped the e-mail wasn’t inappropriate and essentially apologized for bothering me.

Yes, it was a terrible bother. And hugely inappropriate. That’s why I promptly called everyone I knew and screamed, “Will Ferrell sent me a thank-you note!” It more than balances out the occasional e-mail from filmmakers calling me an idiot.

What I’d written was that what makes Ferrell an American treasure is his large-spiritedness: “His heroes are oblivious to the point of imbecility, but it’s not the imbecility that he’s satirizing. It’s the fear. It’s the lengths to which men will go to keep from looking vulnerable (i.e., feminine). His preening Ron Burgundy in Anchorman, his swaggering yet befuddled racer Ricky Bobby in Talladega Nights, his trash-talking figure skater Chazz Michael Michaels in Blades of Glory: They’re child-men who put on macho airs and look more and more like big babies. In his one-man show, You’re Welcome America, Ferrell portrays George W. Bush as an overentitled adolescent posing haplessly (but with deadly consequences) as a Texas cowboy. Best of all is his unemployed 39-going-on-12-year-old Brennan Huff in Step Brothers, which I think is the great American broad comedy of the last decade.”

In person, Ferrell tells me he has always been fascinated by “the macho American male or the overly confident person, because it’s usually a reflection of feeling bad about yourself and overcompensating.” So he deconstructs—even explodes—the paradigm of American masculinity, yet so tenderly you could mistake it for an ode to innocence.

Part of the way he does this is to put himself out there, literally. Since his character’s drunken naked run in Old School, it has become a trademark of sorts for Ferrell to show off a less-than-toned physique and a chest with tight little curls that resemble pubic hair. Which makes him an oddity, even among comic actors. Consider Ben Stiller, whose overpumped frame suggests, well, body issues, and that the anal-retentive persona that Stiller has perfected onscreen is close to who he is. Ferrell, in contrast—

He interjects: “I have to work out just to look like this.”

Adam McKay confirms that. On the phone from Los Angeles, where with Ferrell he co-runs Gary Sanchez Productions, named for a man who doesn’t exist, McKay says, “What’s so funny is he’s actually a really good athlete. He’s run marathons and plays basketball, he stays in shape, he just has a permanent gut. Everyone is so freaked out about it, and he has no problem at all.”

Ferrell says there’s a public-service aspect: “It’s my little message about our body consciousness. We’re so obsessed with diets and plastic surgery, and teenage girls are worried about looking fat in their jeans, and that’s my way of saying, ‘We’re all different shapes and sizes, and it’s okay.’ ”

And also: “It is funny to see characters lose their mind and then, as a result, disrobe.”

There’s another aspect of Ferrell’s comedy that runs counter to the methods of more controlling clowns. He and McKay work with actors who can free-associate on-camera. McKay says that after three or four takes to get a scene down as scripted, he’ll tell the cast to go for it and do the next five or six with four cameras rolling. “That’s the part you’re waiting for,” he says. “All of a sudden you see six other jokes you can do, and then sometimes the actors are tired and I’ll throw out lines—‘Play that angrier,’ or ‘There’s something there, you can find it,’ and Will at this point just knows instantly what I’m talking about, and, yeah, that’s the best.”

“You’ll find a little tangent,” says Ferrell, “or an avenue to go down, and Adam will be writing in his head and say, ‘Maybe talk about the fact that … ’ and that will trigger you, and it’s process, you just learn not to judge what you say, and it’s this whole back-and-forth until we run out of film.”

On Step Brothers—which Ferrell says “lent itself to inane conversations and these two guys just trying to figure things out so we could go and go and go”—they almost did run out of film. They shot an unprecedented million and a half feet. I, for one, wish they could have found time in the final cut for the seemingly endless scene (a DVD extra) in which Ferrell and John C. Reilly don night-vision goggles in their bedroom and lurch around playacting, regressing to their childhood selves, and finally breaking down in tears. The rollicking infantilism is contagious.

Did improv produce, in Anchorman, Ferrell’s musing on his fair city as he sits on a bluff with Christina Applegate: “They named it San Diego, which of course in German means ‘a whale’s vagina’ ”? Wouldn’t it be pretty to think so? It certainly did result in Richard Jenkins’s legendary Step Brothers monologue: “When I was a little boy, I always wanted to be a dinosaur. I wanted to be a Tyrannosaurus rex … I made my arms short and I roamed the backyard, I chased the neighborhood cats, I growled and I roared, everybody knew me and was afraid of me, and one day my dad said ‘Bobby, you are 17, it’s time to throw childish things aside,’ and I said ‘Okay, Pop’ … but he didn’t really say that … he said ‘Stop being a fucking dinosaur and get a job.’ But you know, I thought to myself, ‘I’ll go to medical school, I’ll practice for a little while, and then I’ll come back to it,’ ” to which Ferrell’s Brennan responds: “How is that a skill?”

I digress, but it is difficult not to. The digressions in the Ferrell-McKay movies are always the beauty parts.

McKay was a producer on Casa de Mi Padre, but it was directed by Matt Piedmont from a script by Andrew Steele. Ferrell had the idea kicking around in his head for a few years and enlisted, among others, two of Mexico’s international stars, Gael García Bernal and Diego Luna, to play, respectively, a homicidal drug kingpin and the hero’s flashy, allegedly more clever brother. The laughs are muted, but the movie has a sweet spirit that leaves you strangely happy. Beyond the goofs on telenovelas—the terrible green-screen car rides, the pathetically cheap miniatures—Casa de Mi Padre is, by Hollywood mainstream standards, audacious. It has subtitles. It accommodates social commentary—a hilarious critique of fat, lazy Americans addicted to “shitburgers full of grease,” oblivious to the carnage just over the border in the name of getting their high. It reaches out to a huge swath of the population where Ferrell grew up and lives. It has a scene in which Ferrell goes to bed with the luscious Genesis Rodriguez that segues into a gauzy montage of …

Says Ferrell, “I think in our script it was literally written, ‘Lots and lots of butts, way too many butts.’ ” Butts being caressed and cupped and kneaded and aggressively pinched.

“I thought to myself, (a) ‘You’ve never seen that,’ and (b) ‘We’re going to shoot it with soft lens and make it the most beautiful thing ever,’ ” says Ferrell. “And I knew it would go on way too long and it would either get funnier and funnier to people or it will be, like, ‘Enough!’ ”

No. To paraphrase Christopher Walken’s music producer on SNL, boisterously demanding more of Ferrell’s discordant cowbell accompaniment to what is supposedly the original recording of Blue Öyster Cult’s “(Don’t Fear) The Reaper,” there cannot be too many butts.

This summer, in time for the conventions, Ferrell gets more overtly political with The Campaign, in which he and Zach Galifianakis play rival candidates—Ferrell the slick, Clintonesque glad-hander who secretly aspires to be vice-president, Galifianakis the mild milquetoast recruited by a pair of rich CEOs to run against him. It’s no surprise to hear that the absurdity of the real Republican primaries forced Ferrell & Co. to reshoot scenes to make them more outlandish: They couldn’t compete. Ferrell savors a YouTube montage in which Mitt Romney’s mindlessly dissociated delivery is uncannily similar to Steve Carell’s as the touchingly vacuous weatherman in Anchorman.

He and McKay have projects on the drawing board—maybe even a sequel to Anchorman or Step Brothers, if they can be sure they won’t be repeating themselves. They can afford to take the time to get it right.

Ferrell works constantly but gives the impression of falling into things rather than desperately maneuvering to nail down his next gig. His even temperament inspires much theorizing. McKay says that David O. Russell, an executive producer on Anchorman, has the best take: “He said, ‘Ferrell has the answers that we’re all looking for through meditation and self-improvement. He doesn’t need to examine himself. He just has them.’ He’s not a perfect person by any means. He’ll get pissed off, he’ll gossip, he’ll occasionally have too much to drink; there’s still foibles there. But he’s just one of the most freakishly healthy people.”

I suggest that it’s the Zen ideal: alertness and detachment simultaneously.

“You just described Ferrell. I don’t even think he knows it. I don’t think he knows anything.”

Ferrell doesn’t know if he doesn’t know. “It’s funny,” he says, “I’m very much a let-it-go-to-the-universe type of performer. Don’t worry about every single detail.” He can wait a long time for that whale’s vagina.