Even the most successful screenwriter is ultimately powerless. A writer can’t be sure that a script will ever get made or that, if it does, it won’t be butchered. Given this arrangement, screenwriters typically overcompensate if and when they ever get a chance to direct their own movies. They tend to uncork everything they’ve ever bottled up, spewing out 300-page, umpteen-character scripts about Big Oil (Syriana) or Racism (Crash) to assert their underestimated genius and prove all those meddling philistines wrong. But that’s not how Zak Penn did it.

Penn is a 39-year-old screenwriter who made it big fast. He sold the script for the Arnold Schwarzenegger vehicle The Last Action Hero (co-written with Adam Leff) when he was just 24, and the following year, he and Leff scored with PCU, their send-up of campus life based not so loosely on their experiences as undergrads at Wesleyan. Since then, Penn has been a hired gun, scripting a number of tent-poles including Behind Enemy Lines and two X-Men sequels, not to mention countless uncredited rewrite jobs. But when he finally got a chance to make his own movie, he didn’t feel burdened to make it either a blockbuster or a self-serious cultural pronouncement. He just wanted to make it entertaining, and the result was Incident at Loch Ness, a deeply weird mockumentary starring Werner Herzog, a fake Loch Ness monster, and a Playboy Bunny cryptozoologist. Given the chance to write whatever he wanted, Penn wrote very little—much of the film is improvised, and it doesn’t contain a single monologue.

For his second movie, the poker comedy The Grand (opening March 21; see David Edelstein’s review), Penn ditched written dialogue almost entirely: The whole script barely tops 29 pages. “As a writer, you’re always yelling, ‘Please listen to me! Please listen to me! Please listen to meeee!’” Penn says, sitting in the Whitney Museum’s café, around the corner from where he grew up. “When you do your own movie, you’re in charge. People have to listen to you, so you’re like, ‘Oh … I guess I don’t have to yell anymore … So what do you guys have to say?’”

Penn’s early success wasn’t without a fair amount of frustration. The genre-defying script he wrote for The Last Action Hero turned out to make a pretty crappy movie, and the experience taught Penn that “if you get a bunch of cynical people making a big-budget Hollywood movie, the irony is it doesn’t work.”

That movie, as well as PCU, put Penn on the map, though he didn’t always use his notoriety wisely. “Especially when I was younger, I was at times my own worst enemy, fighting so hard for what I thought was right,” he says, “that I would alienate the people actually making the movie.”

But over the course of working on X2 and X-Men: The Last Stand, Penn says he learned to pick his battles more carefully (he’s most proud of pushing to make Magneto a revolutionary, not just a superficial “supervillain”) and became more sanguine about his failures (“The movie of Elektra is not what I had in my head”). Penn emerged as Marvel Comics’ go-to guy for superheroes, even as his admiration grew for pragmatic auteurs like Woody Allen, Herzog, and Christopher Guest, who don’t fit into the studio system but still find ways to work.

“I grew up across the street from Woody Allen,” Penn says. “He was to me like a god, a secular god.” As a Sleeper-loving kid, Penn wrote an absurdist play about a deranged ice-cream man, but these days, Penn most respects Allen for still making movies on his own terms, regardless of budget. “If you want to do only what you want, be prepared to make no money,” says Penn, who supported the recent writers’ strike, with some reservations. “If you want to get paid, you’re going to have to do something that people want to see. And I’ve tried pretty hard to balance those two things without getting angry. It’s not like, ‘I’m an important artist so I deserve to be rich and do whatever I want to do.’”

For The Grand, Penn conceived a film that could be made on the cheap but with A-list actors, and in such a way that would force him “not to be a megalomaniac.” His gimmick was pitch-meeting brilliant and geared to flatter comedians: Not only would the actors play insane characters in a winner-take-all poker tournament, they would improvise much of the dialogue while playing real hands of poker. Page 27 of the script reads: “Can Larry get over his issues with his dad and his sister?… Can One Eyed Jack save the Rabbit’s Foot?… Here’s the thing: i don’t know. And the reason why I don’t know, yet, is that the final table will be played, in real time, in real life, by our actors. Whoever wins, wins.”

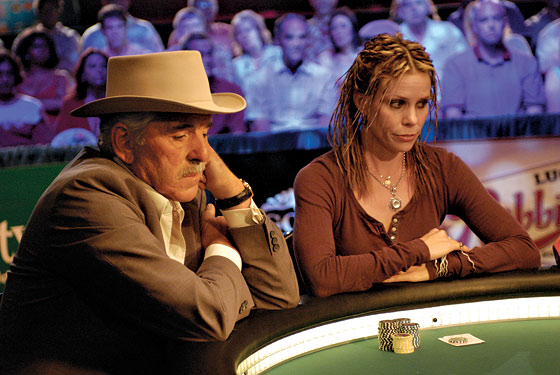

Certain adventurous comedians (and part-time gamblers) couldn’t resist. Cheryl Hines and David Cross, who were already playing (and winning) Celebrity Poker Showdown tournaments, signed up as the feuding Schwartzman siblings, Lainie and Larry. Ray Romano pre-scripted his own riffs as Hines’s fantasy-football-obsessed househusband. Chris Parnell took Penn’s character sketch of a poker genius and turned him into a nut-job hung up on Dune. As the rehabbing Lothario One Eyed Jack, Woody Harrelson not only performed but wrote a love song based on a 12-step program (vets Richard Kind, Jason Alexander, and Michael McKean, plus Penn’s pal Herzog and, yes, Gabe Kaplan, round out the cast). Penn structured the film, fleshed out the characters, and wrote many of their best lines, but on the rest, he literally rolled the dice.

“You were having these real reactions to these cards, but you had to have them as your character,” says Hines. “And it was intense because we all wanted to win so badly.” For the final round of the poker tournament, Penn couldn’t take his hands completely off the wheel, so he gave two characters more chips, hoping that one of them would win. Neither did. “This is why doing an improv movie makes you a better writer,” he says. “What ended up happening was the least story-efficient scenario that I could possibly imagine—and thus feels the most real.”

So how does Penn stack up against improv-legend Guest? McKean, who plays a Steve Wynn–ish billionaire buffoon in The Grand, says Penn is even more freewheeling. “Chris [Guest] and Eugene [Levy] are much more structured, a little more formal,” McKean explains, noting that Penn merrily made dramatic last-minute changes. “His technique is more like those old movies of Ping-Pong balls on the mousetraps: atomic energy. Zak’s crazy as a shithouse rat.”